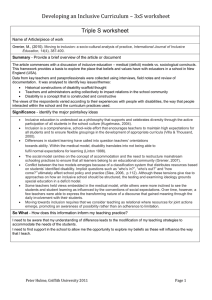

Literature Review of the Principles and Practices relating to Inclusive

advertisement