Leg Ulcers: Part One – Assessment

advertisement

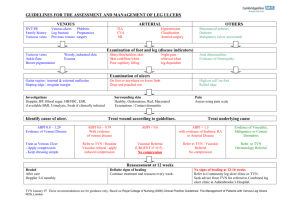

Leg Ulcers: Part One – Assessment July 2013 An overview of best practice ACC Review 52 This article summarises current best practice for leg ulcer assessment. • A leg ulcer is defined as the loss of skin, anywhere below the knee, which takes more than four weeks to heal. prescribed and non-prescribed medications, smoking, nutrition, psychological issues and other factors that may affect healing. • Determining ulcer aetiology is essential before starting compression therapy. Particular risk factors for venous ulcers: Previous or current deep vein thrombosis, varicose veins, immobility, reduced calf muscle pump function, obesity, minor level of trauma, recurrent ulcer, lower leg trauma, and surgery or fracture. • Ankle Brachial Pressure Index (ABPI) helps assess arterial disease severity. Particular risk factors for arterial ulcers: Smoking, hyperlipidemia, ischaemic heart disease, stroke, hypertension and diabetes. • Ongoing ulcer assessment is necessary to monitor progress and recognise any factors impeding healing. Clinical examination • Two-thirds of leg ulcers are venous in origin. Aetiology Accurate diagnosis of ulcer aetiology is essential to avoid harm from inappropriate treatment1. Leg ulceration most commonly follows a minor injury in association with: • chronic venous insufficiency (45-80%) General, including taking blood pressure. A nutritional assessment may include weight and/or BMI, food and fluid intake, hair and skin changes. Limb assessment Both lower limbs should be included in the assessment. The ankle and knee joints should be assessed for mobility. Fixed joints can reduce the foot/calf muscle pump action, reducing venous return. • diabetes (15-25%) Venous disease can be assessed using the CEAP clinical classification tool based on signs of venous hypertension: • hypertension2. C0 no signs of venous disease Most ulcers are associated with venous disease. Less common causes or contributory factors include diabetes, neuropathy, skin cancer, trauma, blood disorders, vasculitis, immobility and infectious diseases. C1 telangiectasias or reticular veins Diagnosis C4b lipodermatosclerosis or atrophie blanche Clinical history C6 active venous leg ulcer1, 3. The patient should be asked how the ulcer began, how it has progressed, and how it is affecting them (including a pain assessment). Past ulcer and treatment history is important. Arterial ulcers are usually found on feet, heels and toes. Signs of peripheral arterial disease include atrophic shiny skin, pale and cool feet on elevation, venous guttering, hair loss and nail thickening. The detection of underlying joint problems and neuropathy is essential. • chronic arterial insufficiency (5-20%) General and particular risk factors should be noted, including past and concurrent medical conditions, C2 varicose veins C3 presence of oedema C4a eczema or pigmentation C5 evidence of a healed venous leg ulcer Please send your feedback to ACCReviewFeedback@acc.co.nz Ulcer assessment Ulcer assessment will help determine the underlying aetiology and factors that may have a detrimental effect on healing. Venous ulcers are relatively painless, unless infected, and often associated with swelling. Arterial ulcers are frequently painful, with borders of lesions appearing as “punched out”4. Measuring the ulcer provides a baseline to compare progress. Ruler measurements of width, length and depth, digital images or tracing onto transparencies are useful methods. Wound assessment using the “TIME” acronym is helpful: T – appearance of tissue in the ulcer bed, I – signs of infection and inflammation, M – moisture level, type and colour of exudate, E – the condition of the wound edges and signs of epithelialisation. Investigations Blood screen May include blood glucose, haemoglobin, urea and electrolytes, serum albumin, lipids, rheumatoid factor, auto antibodies, white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein and liver function tests. Bacterial swabs Should not be taken routinely and only where clinical signs of infection are present, so to assist in determining appropriate sensitivities to antibiotics. Biopsy of the ulcer May be required if malignancy or vasculitis are suspected. Ankle Brachial Pressure Index (ABPI) Using Doppler ultrasound determines the level of arterial blood flow to the lower limb. The systolic blood pressures are recorded in the arms and ankles. A calculation is used to determine the ratio of blood flow. An ABPI of 0.8 to 1.2 indicates good arterial flow; readings of <0.8 are suggestive of arterial disease and patients with such readings should not have high compression (40 mmHg) applied to their leg. Patients with an ABPI reading between 0.6 and 0.8 may be suitable for reduced compression. Readings of >1.2 suggest possible arterial wall calcification and therefore ABPI readings are considered unreliable. Duplex ultrasound Is a non-invasive ultrasound scan to investigate venous or arterial blood flow in the lower legs; it can identify either arterial obstruction or incompetent veins. Reassessment Reassessment should be carried out regularly to monitor progress and ensure healing is progressing within the expected time frame. Most ulcers should decrease by 25% ACC6672 July 2013 ©ACC 2013 in four weeks and heal within 12 weeks. If this does not occur, referral to specialist services should be considered. Criteria for referral to specialist services • Uncertain aetiology • Atypical characteristics • Suspicion of malignancy • ABPI < 0.8 or above 1.2 • Correctable superficial venous insufficiency • Rheumatoid arthritis or other suspected condition associated with vasculitis • Dermatitis refractory to topical steroids • Failure to respond to conventional treatment after four weeks and/or failure to heal within 12 weeks • Recurring ulcers • Antibiotic-resistant infected ulcers • Ulcers causing uncontrolled pain. ACC cover ACC provides cover and entitlements for personal injury. If a leg ulcer is the consequence of a pre-existing disease or other underlying condition, rather than the consequence of personal injury, the patient will not be entitled to cover from ACC. It is important to consider the nature and cause of any ongoing problems and establish a causal link between these and personal injury. Most injury-related ulcers should have healed by three months, and any ulcers lasting longer than this should be considered as possibly no longer related to covered injury. References 1. Australian and New Zealand Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention and Management of Venous Leg Ulcers www.nzwcs.org.nz/publications 2. DermNetNz http://www.dermnetnz.org/site-age-specific/leg-ulcers.html Accessed 20/05/2013. 3. Eklöf B, Rutherford R, Bergan J et al. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2004; 40(6):1248–52. 4.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence – Leg Ulcer – venous http://cks.nice.org.uk/leg-ulcer-venous#!topicsummary. Accessed 01/05/2013. Endorsed by the New Zealand Venous Leg Ulcer Advisory Panel on behalf of the New Zealand Wound Care Society.