HARVARD

MOUNTAINEERING

Number 25

DECEMBER 2004

THE

HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING CLUB

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

Editor

Lucas Laursen

Photography Editor

Joseph Abel

Copy Editor

Pien Huang

Assistant Editors

Allegra Fisher

Akash Kanoji

Joshua Neff

Corey Rennell

Copyright © 2004 The Harvard Mountaineering Club.

All rights reserved. No portion of this Journal may be reproduced in

any way without written permission of The Harvard Mountaineering

Club.

For more information on Harvard Mountaineering or The Harvard

Mountaineering Club, contact us at:

The Harvard Mountaineering Club

1st Floor, University Hall #73

Cambridge, MA 02138

Electronic inquiries should be directed to:

mountain@hcs.harvard.edu

The Officers of the Harvard Mountaineering Club

dedicate this Journal to

the next eighty years

of Harvard Mountaineering.

HMC Officers, 1995-2004

2004-05

President: Lucas Laursen

SecrefaJJI.' Joshua Neff

Treasurer: Joseph Abel

Cabin Liaison: Jeremy Hutton

Equip. Czar: John Noss

1999-2000

President: Mike Weller

Secretmy Coz Teplitz

Treasurer: John Higgins

Cabin Liaison: Glenn Sanders

Equip. Czar: Lucas Marinelli

2003-04

President: Robert Aram Marks

Secretwy· Jane Kucera

Treasurer: George Brewster

Cabin Liaison: Jeremy Hutton

1998-99

President: Lauren Hough

Vice-President: Josh Eisner

Secretmy: Pattycja Paruch

Treasurer: Mike Weller

Equipment: Tony Patt

Cabin Liaison: Luca Marinelli

Wall Liaison: Meredith

2002-03

President: Kyle Peterson

Cabin Liaison: Jeremy Hutton

2001-02

President: Vince Chu

Secretmy: Kyle Peterson

Treasurer: John Higgins

Cabin Liaison: Glen Sanders

Equip. Czar: Jeremy Hutton

2000-01

President: Mike Weller

Secretmy Coz Teplitz

Treasurer: John Higgins

Cabin Liaison: Glenn Sanders

Equip. Czar: Lucas Marinelli

Website: Petar Maymounkov

1997-98

President: Mike Dewey

Secretmy· Whit Collier

Treasurer: Anna Liu

Equip. Czar: Noah Freeman

1996-7

President: Mark Roth

SecretmJI.' Whit Collier

Treasurer: Willy Danman

Librarian: Anna Liu

Equipment Czar: Steve Tregay

1995-6

President: Mike Liftik

Secretmy Mark Roth

Treasurer: Rebecca Taylor

Librarian: Mike Dewey

Equip. Czar: Noah Freeman

Contents

lCknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

'oreword ............. ..... ............................... ...

3

'ales of lee ....................................... Will Silva

5

:ookies on Half Dome .................... . .Andy Martin

17

'he West Buttress .................... .Adilet Imambekov

21

low to Climb a Stream ................. .Ko Takashima

29

'en on the Hat .............. .Andrew Richardson et al.

34

~etaliation ................................. Glenn

Sanders

37

'he Flume .................................. ...... Katie Ives

37

)ne HMCer's History ..... .... William Lo-well Putnam

43

:abin Report ............................. .Lucas Laursen

45

n Memoriam...............................................

46

!lembership of the HMC..... .. . . . . ... . . . . . . . .. . . . . ... . . .

47

7opies o.f this and previous issues a./Harvard Mountaineering are

vailable on request at $10 each Fom the Harvard

51

1ountaineering Club, ] Floor University Hall #73, Cambridge,

1A 02138, USA.

1

Acknowledgements

This Journal contains the amalgamated work of several

generations of Harvard mountaineers, only some of who have been

in communication with one another, and fewer of whom can be

recognized here.

I would like to express gratitude to the anonymous donors

and HMCers who have left the HMC with a healthy journal fund

over the years, saving this generation that undertaking.

More recent donations directed to the journal have come

from Bill Atkinson and John C. Oberlin, both Life Members.

I would also like to thank the authors whose work appears

here without their knowledge. Andy Matiin, Ko Takashima, Glenn

Sanders, and Katie Ives all left articles with previous HMC

officers. It was their work that Kyle Peterson, HMC President in

2002-03, passed to me and which forms the core of this Journal. It

is my hope that the present form of their writings retains the voices

of these contributors, in spite of not knowing them personally.

I am grateful to the recent contributors for their cooperation

during the drawn-out process of editing and layout.

Aram Marks, HMC President in 2003-4, and Janie Kucera,

HMC Secretary in 2003-4, drove the revival ofthe HMC

newsletter, Notes from Cambridge, last year, and inspired the

revival of the journal this year.

Equally deserving thanks here are the editing teams that

have put together previous issues of the journal, whose works

guided this year's editors.

Erin Matiin of Harvard Printing and Publishing Services

made the digital printing process painless.

My final thanks go to my girlfriend, Erika Hamden, who

gracefully put up with periods of absence, distraction and more

than the usual mouintaineer's slovenliness during my involvement

ll this journal.

-The Ec

2

·v1eword

The Harvard Mountaineering Club in its eightieth year

inds itself not that different from the last time this journal was

mblished, on the Club's seventieth. My predecessor as Editor and

>resident, Andrew Noymer, commented then on the grand history

>f the first fifty or so years of the Club's history and asked how

nodern members could hope to carry on the tradition of world:lass climbing. The HMC has not been doing new routes or even

mblishing this journal since then. Life Member Mack Beal put it

nore bluntly when he wrote us in January 2003, "What the hell is

~oing on with the HMC???"

Since Mr. Beal wrote us, the HMC has sent Notes From

-..:ambridge to its mailing list twice, and this journal is proof that

he HMC continues to serve its members as a source of climbing

>artners and mountaineering camaraderie. Recent alumni

:lideshows by John Graham and Pete Carman and Bradford

Nashburn and Bob Bates have helped renew alumni ties.

This is not to say that the HMC has climbed Mount Saint

~lias recently (a notable HMC ascent in Mr. Beal's day) or built

my new cabins (another notable HMC activity, ca. 1932 and

.963). Today's HMCers tend to climb local rock and ice at Quincy

2uarries, Cathedral Ledge, and Huntington Ravine during the

erm. They spend their shorter school breaks climbing, but in the

:ummer, climbing is often just a break between weighty final

:xams in May and time-consuming summer jobs. In this issue,

\dilet Imambekov recounts his climb of Denali last summer by the

nute pioneered by Life Member Brad Washburn-but the climb

ook place with Russian friends of his from the Boston area. The

.rMC is no longer, in the words of Life Member and writer David

~obetis, "the most ambitious collection of undergraduate alpinists

n the country." 1

Roberts, "The Hearse Traverse," in Escape Routes, (Seattle: The

1neers, 1997) previously published in Summit as "Rites of Passage."

3

Noymer's generation responded by aspiring to "tlu;; vc;1~

routes the HMC was putting up 20 years" 2 before. Our generatior

has done the same. But for the HMC to continue to do excitin~

climbing, the three-year incubating period of the standan

undergraduate is not long enough. To lengthen our "institutiona

memory" this generation must sustain its contacts with recen

alumni (see George Brewster '03 in action on page 38) and build'

base of experienced graduate students (see Adilet Imambekov':

article on page 21) and others. Will Silva's contributions t<

Harvard Mountaineering span decades (on page 5), and it is hope<

that the same will be said of more recent alumni.

This Journal, published after the longest gap between issue:

of Harvard Mountaineering in the journal's history is not intende<

as the definitive recapitulation of the turn of the millennium. Th1

atiicles were collected haphazardly and the mailing list i:

incomplete. The articles cannot reflect all the adventures of recen

members of the HMC. Instead it goes to press as some HMC

members are planning an expedition to Mexico, and others an

preparing for an attempt of the storied Presidential Traverse. Tha

is as it should be. The potential for frequent, ongoing, routin1

publication of this journal is great in a time of digita

communication, editing, and publishing and could unite scattere<

HMCers. Already most of the articles here come from members fa

from Cambridge. Please consider this an invitation to submi

material to the next issue and to strike up contact with fellov

HMCers.

It is hoped that this journal will spark a renewal of th1

historically close relationship between HMC members an<

alumni-an integral part of the HMC's early years and the ke;

ingredient to its legendary climbs.

-The Edito

1drew Noymer, in the Foreword to Harvard Mountaineering 24, Jun

4

~~-J v~

Ice

Vill Silva

The Cave: Mt. Foraker, May 1997

The radio that night predicted clear weather the next day,

by a storm the day after. None ofus had the desire to sit

ut a storm. Jim Beall, John Lehman, and I had begun ferrying

)ads up Mt. Crosson ten days ago to get us in position to climb

!lt. Foraker by way of the Sultana Ridge. Conditions for climbing

1ight have been bad after a storm, and we would have had to

~supply at the cache we had left earlier on the Sultana route before

tarting for the top. Instead of waiting for the storm to pass, we

mnched our summit bid early in the morning, from lower than we

ad planned.

After an hour, we reached one of the igloos a previous

'arty had built and cached most of our gear. With only our down

'arkas and a big lunch we headed for the summit, still several

niles of treld(ing and a vertical mile above us. At the last moment

put a stove, pot, shovel, and fuel in my pack. I cached these in

nother igloo at the foot of the ridge an hour later, figuring we

vere in for a long day. The wind had already increased, and a

ircle had formed around the sun. High clouds were thickening.

Oh well, that's tomorrow's storm gathering," we told ourselves.

Hours passed as we climbed. Clouds moved in, hiding first

he sky, then at times the sun. We continued, thinking that this was

naybe just a local cloud. It grew windier and colder, but we

limbed higher. My doubt grew when I noticed that I could no

~nger see the glaciers below. We halted and huddled under my

1ivy shelter to eat, drink, and confer. John's altimeter watch read

5,000 feet and 2PM. We decided to climb for another half hour

nd see if conditions would improve.

At gusts of up to 50 miles per hour, we started again. Soon

~- .. l-1 hardly see John at the lead end of our rope, let alone hear

Jim. With 1,800 feet to go, things were getting out ofhand.

~llowed

5

The sun was gone. The valley was gone. Visibility was 0 ulll0

We started down.

The first two thousand feet of descent went all right, bu

suddenly fog surrounded us. Which way? The three of us ha<

three different ideas. We shot the compass and John led off. Wt

had left only occasional wands above the bergschrund, having use<

most of our wands to flag our way back along Sultana Ridge an<

over Crosson. It was too cold to stand still and wait for glimpse~

that might give us a better idea of our position. After a falst

attempt, heading too far west and getting into crevasses, Wt

reached the snow cave. As evening gathered, John tried to descen<

beyond, knowing the igloo with our stove was just 500' lower, bu

it was impossible. We were in for a night in a cave.

I have made only a couple of unplanned bivouacs in 2~

years of mountaineering. Those followed long summer rod

climbs, and had little in common with the predicament we faced

Though sheltered from the storm, we were curled up on snow

hungry and thirsty, without sleeping bags or enough warn

clothing. The temperature dropped to -1 OOF as night fell. I wa~

lucky enough to have a short piece of a foam pad; this gave me tht

luxury of putting my legs in my rucksack, while my friends had t<

sit or lie on theirs. The night passed slowly as we dozed and trie<

to stay warm. After the initial anxiety had passed, my mind wa~

quiet. I felt a certain disbelief that we had let ourselves get caugh

by the storm, and wondered how long I could sustain the warmtl

within me.

By morning, the visibility was no different, but it wa~

brighter and easier to stay warm. Blindly, we set out for the iglo<

where I had cached the stove. John had led the section during tht

ascent and had seemed most able to navigate to the igloo, but Wt

were extremely disoriented.

Finding a wand did not hell

determine our position; we didn't even know if it was ours. Onl)

:r John fell off the corniced edge of the ridge, fortunately into <

: snow, did he realize our location. We quickly eros

rund and found another wand. While its surroundings 1

6

-~-.. wwnce

to the igloo site of the day before, we were sure t

1e wand was ours. After guessing where the door would be, I < ~

own three feet and punched through into the igloo entryway.

oon, we were safe from the storm and gratefully brewing some

rarm liquid.

Overly optimistic about finding the other igloo, where we

ad left our camping gear and food, we ate most of our remaining

mch, and set out at 2 PM with plenty of hot water. We didn't

mke it very far. Third on the rope, I had lost sight of the leader

efore the slack was out. Realizing that we were unlikely to avoid

1e now invisible, thinly covered crevasses we had passed on our

scent or even to find our camp, we turned back towards the first

~loo and resigned ourselves to a second night out.

The cold came on more quickly this time. I didn't want to

1ove to let the cold air into my clothes, but I couldn't sit still for

mg without getting freezing cold. We sat in close contact, and

little; what was there to

hour or so, we would

.. 1

oraker - Will Silva

7

shift to change the positions of our stiffening backs. In spik u1 tu

shared body heat, we were frigid by midnight. Nobody had slep1

How long could this night go on? We brewed up again and ate .

candy bar. My lunch bag was empty except for a granola bar, .

few nuts, and ten squares of chocolate. I pictured a flam

flickering in the wind. Jim's zipper-pull thermometer read -10°F.

Minutes crawled by with no dozing to offer relief. I dull:

wondered what the next 12, 24, or 36 hours might bring. Th

prospects were grim. We kept shifting positions every half hour tc

hour, exchanging few words. My shivering came and went.

thought ofvery little beyond the immediate: I'm cold. We're in:

hell of a fix. What's to come of it? Can't think of anything els1

we can do. What time is it? Will the storm quit?

Finally at 0630 John got up and said it out loud. "I'm cold,'

he said. "We've got to get out of here." He was right. We needec

to move while we still had the strength. After 24 more hours in the

igloo we might be too hungry and weak to make it back to camp

John moved out into the dome of the entryway and with his ice axe

made a small hole in the roof where a little light showed.

"Blue sky out there!" Hope welled up in my throat. Hen

was our chance! We brewed warm water for our bottles an<

prepared to leave. I began to dig out the entrance, pushing the

snow behind me as my friends cleared it back into the igloo

Tunneling up through another five feet of snow, I broke througl

into bright sunlight. Blue sky all around! Yes! Emerging fron

the snow, I felt reborn, blinking at the scene, seeing nothin!

familiar save Mt. Foraker far above us. Wild sastrugi and drift:

covered what had been a broad flat saddle. The others passed th<

packs out to me before exiting, then we roped up and I led off.

For an hour I trudged through the snow, up and over hills

around seracs. Two thousand feet below us, dense clouds filled th<

valleys. Would they stay down or rise, as the morning sun warme<

air? In some places the surface had been blown clear and w<

ld see old frozen crampon tracks. When I waded up

~hs in soft snowdrifts, I'd get down on my belly and

8

----·uo the strength to plow through them. When I could feel

1ottom again I'd get back on my feet as though wading ash

\.drenaline was giving way to fatigue when I finally tumed a

:omer into a saddle where I thought I could see our igloo camp.

v'ly heart sank when I saw only a rimmed boulder. I swore softly,

1itterly, but my partners had seen that the camp was up on the next

ise just a few hundred yards ahead. They took the lead, and soon

ve were digging out the igloo entrance, chinking the cracks,

naking our camp tight against the howling wind. Inside, we ate,

!rank, luxuriated in stretching out full length in our warm bags,

lnd slept like the dead.

Several days later, I sat on the col between Peak 12,472 and

v'lt. Crosson. The soft evening light lent a warm color to Jim's face

lS he sat writing in his journal. Soon alpenglow painted the

:ummits of Foraker and Denali. I felt at peace. How strange, this

ife; a few nights before I'd have given anything to be anywhere

~lse. Now I could think of nowhere I'd sooner be, and nobody I'd

:ooner be with than Jim and John. All was perfection.

I. The Dome: South Pole Station,

October 1997 to November 1998

Had someone told me back in the Cave that I would spend

he next year at the South Pole, I don't know whether I would have

aughed, wept, or cursed. Still, a few months after Foraker, I found

nyself with a new job: South Pole Doctor. I spent 13 months on

he Pole, finding personal and professional fulfillment in my role

,vithin that unusual community.

9

The Dome

Will Silva

1.) Light: January 1998

January 1998 was among the cloudiest months on record a

South Pole Station. Temperatures ranged from -25°F to a balmy

10°F. I went out skiing almost evety night, enjoying the light

relative warmth, and ease of passage. Many of these trips were int<

the teeth of the wind, and I remember the streams of ice crystal:

wending over the surface like the channels of a braided river. A

times low clouds cut the visibility to a few hundred yards. Ofte1

the layer was shallow, tearing open to show ragged blue overhead

I would ski for a couple miles beyond the runway, stopping t<

rvel at the absence of man and the accompanying silence. A

m or midnight, the sun remained at a constant elevatic

::;ribed circles around the polar sky.

10

1 loved the excursions on brilliantly clear nights best. 1

[ could ski out from the station and see all five of the b

plywood visibility markers that the meteorologists had placed a

mile apart. Those nights the sun held a little warmth, the sky was

brilliant blue, and occasionally the wind dropped. I'd head out into

the wind with just a fleece jacket, Carhartt bib, and an anorak over

my indoor clothes. At that time of night, the sun stood just off my

right shoulder, making magic of the snow and sky. It rested atop a

pillar of fire, and its mirror image sat on the horizon beneath it.

Showers of faceted crystals in the air refracted the light into

circular rainbows around the sun. On the glacier, these same

crystals caught the light and bent it, sparkling in bright colors

around me. All around danced brilliant red, gold, deep blues, and

emerald greens. By mid-January the sun had dropped enough that

the horizon cut across the solar haloes. A parabola of glittering

colors stretched from either end of the halo to where I stood, and

followed along as I traveled at angles just off the sun. I fancied

myself flying over a mythical land, as I skied along paths of drifted

powder on the crystal plain.

2.) Darkness: August, 1998

Let me tell you a tale of darkness, while it still rests heavy on this

wintry land. I must tell my tale before the returning light gives it

the appearance of a lie ...

Let me speak of darkness so deep you see your hand before your

face only when it hides the stars. Darkness so deep I imagine

myself on the far side of the Moon, or walking in a dream of

brilliant stars, crystal shards lying on black velvet that reaches out

forever. My face presses against that velvet, presses the void. ...

I'll tell you ofmoonlight, the day's ghostly twin, of unearthly light

cast over frozen lands, of moon rising through haze, a promise of

dawn to come, ofsky's shimmering seam, the Aurora Australis ...

11

The sun set on March 22 and rose six months mLc;l.

Temperatures averaged around -80°F, sometimes rising to -65°F

and dropping a little below -1 OOOF on many occasions; our nadir

was -105 OF. The phases of the Moon lent a welcome structure to

the darkness. The stars were brilliant during the dark of the night:

Rigel, Sirius, Canopus, Achernar, Rigel Centauri, Antares, and

Fomalhaut became the landmarks of our sky. The Milky Way,

called the Silver River by the Chinese, had never seemed so grand.

Scorpio was magnificent, curling across the sky. Scorpio Rampant!

Watching for a few minutes, I'd often see a shooting star. Against

these dark skies the Aurora Australis came alive. The aurora varied

tremendously, from dim to brilliant, from amorphous to structured,

from still to wild, dancing motion. Most of the time it appeared to

be pale green, corresponding to excited oxygen atoms returning

from second to first quantum state. Once after I'd stayed up late

finishing a report, I was spinning dreams when Johan came on the

11 Silva On (The) Ice- Courtec\Y Will Silva

12

... ~au

at 0730 saying there was a big, bright aurora overhea

tlready had my boots on when he all-called again, saying he

nistaken; it was really huge, red, and dancing! I was out the door

;wiftly, from my warm bed to a (polar) moderate -75°F with 12

mots of wind, and Oooh, the daylight in the darkness! The aurora

·eflected on the Dome's metal skin, lighting the snow surface so

mildings could be seen half a kilometer away. Gigantic cords and

)ands seemed shaken from one end as though by a giant hand.

;himmering curtains of rays and shafts of light swirled, folded, and

:urned on itself, with waves traveling across the sky in seconds.

3eneath the aurora, Earth appeared as a living, shimmering

)fganism, a jewel of creation.

With darkness and isolation, my horizon has shrunk. We have

'wd the stormiest winter of the forty winters people have spent at

rhe Pole. Even though I've gone outside eve1y day, the overcast sky

rws seemed nearly as confining as the dome. L(fe ~was spent mostly

indoors during the summer, but has been almost entirely so for the

rast 5 months. Not a hard life; it's warm, the power's reliable, the

rood is decent, and for the most part our crew has enjoyed good

l1ealth and morale. But ~winter makes a year at the South Pole akin

to a space voyage. While summer brought an expansive emptiness,

winter brought gates shut against the vast, threatening openness

beyond. The astronomers look out, but my frontier is not the space

beyond; it is the space within. The horizon has become internal.

III. Sun and Shadow: Mt. Aspiring, January 1999

The imposing Mt. Aspiring dominates its surrounding

landscape of peaks and valleys. Aptly named, it towers over the

Bonar and Volta glaciers of the Southern Alps in New Zealand.

The southwest ridge sweeps gracefully from the glacier to its

summit at 10,000 feet, with the pitch increasing from a gentle 30°

-'- --- to 50° near the top.

13

Glaciers? Most of our former crewmates thought :Ruut;ll

Schwarz and I were utterly mad to seek ice and snow after a year

of living at the South Pole. A Bavarian astrophysics student,

Robert had spent two years straight at 90° S. What a wonderful

world of difference there is, though, between the Polar plateau and

the mountains of temperate New Zealand! We hiked ten miles

through the cow pastures and grasslands of the West Matakituki

River Valley. A washed-out, brushy trail to the French Ridge hut

made me feel as though I were in the North Cascades. Once at the

hut, we spent a rainy day becoming acquainted with the local keas.

These mountain parrots are playful but destructive characters, and

a source of great amusement as long as they are dismantling

somebody else's gear.

The following day's challenge was to find a way up the

Quarterdeck, a glacial ramp leading onto the Bonar Glacier.

Though January 2 was still early in the usual Kiwi climbing

season, a light winter's snow pack and glacial recession made for

difficult passage among the crevasses. Bridges that others had

crossed a week before had collapsed. Ultimately, we were forced

onto seasonal snow, overlying wet rock slabs at the edge of

Gloomy Gulch. Unnerved but not unhappy, we reached the col to

the Bonar by late afternoon and traversed to the shoulder of Mt.

French, where we found gravelly ledges for a bivouac across the

glacier from Mt. Aspiring. We crawled into our sleeping bags as

alpenglow faded from the summit.

For just a moment after the 0300 alarm sounded I thought

that I was back at the Pole. The Southern Cross and Scorpio hung

high overhead, nearly overwhelmed by a full moon. It was cold

out, but not that cold! Soon Robert's and my crampons crunched

into the frozen glacier as, roped up, we headed across to Aspiring.

What a treat! Without wind, the stillness and moonlight amplified

the drama of the ridge stretching above us. Dawn found us on the

: of the lower ridge, after crossing the bergschrund on a fragile

Nell frozen bridge. Off to the west, a rosy band capped r

ow on the haze; Mt. Aspiring's own shadow made a

14

...... tu~

pale moon above. We put the rope on for a short, s

~oclc step and then began to solo up the low-incline ice on the'

~ide of the ridge. The sun rose, lighting up the steep east face. For

:wo hours we moved up by pied plan, with one foot flat and the

Jther on front points. The ice was sound and porous, straight out of

ny late-night polar fantasies. Higher and higher, ever steeper, the

ridge led us to the rock bands at the summit. Reaching them, I

::hopped a ledge for Bert, then took out my second ice tool to move

Lip and left, around a corner, to look at the exit couloir.

Belayed off a few ice screws, I moved up bulging ice that

reminded me of the first pitch of Pinnacle Gully, in Huntington

Ravine. I grinned thinking back, while looking up at sun on the

summit ridge above. Soon we had the rope off again and were

front-pointing the last few hundred feet. Turning a small cornice,

we moved from shadow to sunlight. Mt. Aspiring lay below us

with peaks, glaciers, verdant valleys, and the ocean beyond. A

clear blue sky lay above us. I felt like I was floating at the center

of the sphere of being. It was good to be back from the ice.

15

~~~-''-lC''>

on Half Dome

\ndyMartin

Stomping down the trail to the base of the Regular Northwest

ace ofHalfDome is an uncomfortable affair: the brief descent comes

tt the end of an eight-mile uphill approach carrying the most illlesigned packs in common usage - haul bags. One of my partners,

vlike Dewey, decided that breaking in new hiking boots would bolster

t sense of manliness left severely flagging after a summer as a

lesk jockey in New Mexico. Neither Noah Freeman nor I needed

my more suffering than the trail had dished out already.

Our plan was this: fix ropes on the first two pitches of the

route, wake before dawn, and fire on up to the bivy at the top of

the eleventh pitch. Two days thereafter we would summit, have a

leisurely stroll down to Camp 4, and await the ticker tape parade

reserved for noble adventurers of our mien.

Noah and Mike swapped leads on the first two pitches,

fixed lines and rapped as Half Dome lit up deep purple with alpenglow. We chowed, racked our gear at the base, and gave ourselves

an inspirational talking to, along the lines of "we have nothing to

fear but fear itself." Slightly before our alarms went off that fateful

morning we heard, far away, a faint whistling growing steadily louder

and nearer. As we roused ourselves and shook off the mental sludge of

the night before, we were greeted with the BAM! BAM! arrival of two

chunks of rock at the base of our route. We hit the deck as the sparks

flew, lighting up the morning well before first light.

We let out a collective "Whoa, dude, I guess it's time to

climb now." I think if we hadn't gotten the alpine start,

clearheaded thinking might have prevailed and we would have

reclaimed our ropes and not undetiaken the groggy early-morning

adventure. But that is the greatest asset of the alpine start, fi1m

snow and ice notwithstanding: one gets underway before the

conscious mind is ale1i enough to object to the dangers involved.

it is alert halfway up a pitch, loaded with endorphins, all it can

"why don't I do this more often?"

a Fox on the Mushroom Planet- George Brevvster

Pitch followed pitch followed pitch of monotonous cracks,

more monotonous hauling (two-man hauling because we had so

much weight), and still more monotonous belaying. The end of the

first day found me and Noah groveling in a puny crevice ror

placements to bolster a pathetic belay at a minuscule stance, while

Mike followed on the Robbins bolt ladder, cursing and bitching the

whole way. Noah led the last pitch to the bivy in near-pitch darkness,

despite never having aided before. At one point J heard

"AHHHHH .... FALLING!" and watched in amazement as Noah pitched

off the face of the clifflike a cartoon character shot out of a cannon.

I locked off my belay device to catch the impending fall only to watch

Noah stop without my catching him at all. He had left an aider in

place, and somehow managed to clip into it during his fall. We

finally staked out our claim to the ledge at the top of pitch eleven.

We clipped our haul bags in, pulled our sleeping bags out, chowed

down on the cans of Campbell's soup we had laboriously hauled up,

and generally made like mountain hardmen.

The second day began with a strenuous lead up a tight squeeze

chimney, ending with a burly and horrible off-width move high

above my last protection. Thankfully, I didn't fall. The bulk of that

day was more of the same: grinding endlessly through deep nasty

chimneys and jugging below the haul bags to keep them free while

they repeatedly got snagged just out of reach. I found myself pinched

between haul bags, under overhangs, and between chimney walls, all the

while suspended two thousand feet above the ground. I was unable to

move or effect change of any sort, and was verbally pummc~ed by

two irate guys above me who I had until recently counted as fncnd~.

We eventually clawed our way up and belly-flopped onto Big

Sandy with a collective "Whoa dude ... Whooooa." We were able to

' sprawl out w h'l

t

leisurely

unrope on its extensive ledges and

1 e we a e a

· . ·

meal. Night fell over a far more relaxed trio than the previous nl~hl.

. hghts

·

and we watched over the emergmg

ofthe va 11 ey be10 "v us· l1kc

.

.

tauts soanng htgh above the rest of h umam'ty · 0 ne of the true1,

. headlamps htgh

. up on W as h'mgton's Column

vas spottmg

..

' JJITlO

ve that we were in the company of like-minded spmts.

18

The next day a party of three from Ecuador passed us a

slogged through the zigzags. We watched them shimmy across 1 ~~-·~·

God Ledge while we dangled from our thin nylon tether thousands of

feet above the Valley floor. We could not finish soon enough. Summit

fever was burning hot. I finished leading Thank God Ledge and sat

waiting for the Ecuadorians to clear a spot for my belay, when I felt

my trail line go tight, as Noah and Mike, in their impatience,

prepared to jumar a line with nothing but me as the anchor!

Noah led the final pitch, hauling himself over the lip of the

face and onto the summit just before sundown to the glorious sight

of full moons. Several stark naked girls greeted him and offered

him a Nutter Butter cookie. A gentleman even on a climb, he

obliged, but it saddens me to report that he neglected to set any aside

for his companions still slaving away below. By the time we hauled

our weary masses up to that final anchor, the ethereal beauties had

disappeared into the night, leaving Noah with nothing but a great

story and an empty wrapper. The sweetest moments of that day were

those spent coiling the rope on the summit, razzing Noah about the

naked ladies on his dehydrated mind.

We trudged down the Half Dome cable route. Soon the

accumulated fatigue of the previous three days began to catch up

with us and, having not packed a dinner for that night, so did the

hypoglycemia. Until that night I had always felt I would be able to

push through any sort of grueling physical outing to arrive at camp

before sleeping but as the hours wore on, sleeping on the trail seemed

to be a more and more appealing option. Without Mike Dewey's

repeated urgings to get to Camp 4 that night, that day would have

ended for me somewhere between Vernal and Nevada falls, in the

stomping grounds of Noah's nocturnal nymphs. As we crossed a

bridge over the Merced that night, I felt a sense of closure looking

back at Half Dome; it was a mere silhouette towering above us as the

moon flickered off of the river below us. Half Dome was an X that

marked a wonderful spot in our memory but she seemed startlingly

,_ ~~-1nged, so beautifully indifferent to our passing.

19

____, " ~st Buttress

Adilet Imambekov

After months of training in the White Mountains,

expedition "Denali Union" via the West Buttress had begun. Three

members of the ex-Soviet climbing community I had met on the

Intemet joined me. Alexey Dokukin, an experienced climber and

Everest summiteer, served as the head of our expedition. His wife

Zulfiya Dokukina, another veteran of Denali, accompanied him.

Our last comrade was Dmitry Shapovalov, a grad student from

Johns Hopkins University who had summited Peak Lenin in

Kyrgyzstan, leaving me as the least experienced climber, with only

Mont Blanc on my trophy wall. But now I was en route to climbing

North America's highest peak, Mt. McKinley, and Mt. Foraker, the

second highest peak in the Alaska Range.

I flew into Anchorage on May 19. Although not yet in the

wildemess, I found my Thermarest handy on the plane. The air

was so fresh in Anchorage, and you could easily feel its purity in

comparison to Boston. The next morning we got up at 7 am and

picked up gas canisters at REI, along with some minor things we

were missing before hopping on the 4 pm "Talkeetna Shuttle."

Talkeetna, though typically a small town of around 300

inhabitants, was bustling with tourists and climbers during the

summer months. That night we went to Talkeetna Beach to see the

mountain. The air was clear, though the clouds hid the summit.

The moming of the 21st we ate breakfast at "Road House,"

a climber's favorite. Alaskan-sized breakfasts are even bigger than

the standard American size, and even with my Kazakh-sized

appetite I couldn't finish all of my meal.

We checked in at the Talkeetna Ranger Station where the

ranger gave us a special portable toilet to be used above the 14000'

camp and biodegradable packs to be used below. They told us that

over this calendar year, approximately 1500 people had registered

ali from Kahiltna Airport- Dmitry Shapovalov

21

to climb and twelve parties had successfully summited.

The plane dropped us off at the Kahiltna Glacier Airport

where we had some light snacks and then headed out for the 7800'

camp around 5 pm. Fortunately it doesn't get dark in Alaska in the

summer, so you can climb at any time of day. Nonetheless,

visibility was pretty poor and it was snowing. Most of our gear we

carried in the sleds, only porting our down clothing and sleeping

bags in the backpacks. For dinner we had a hefty mountain meal of

fried bacon with buckwheat. We were finally on the ice.

We took the first few days pretty slowly. Visibility was

worse than the day before and it took 3 hours to get to the camp at

9400'. The weather remained bad throughout the next day with

heavy snow and poor visibility so we decided to make May 23 a

rest day. We spent the day in the bigger tent eating and playing

cards. At one point a little bird came into our tent to warm up, but

once it started flying around and threatening to leave us an

unwanted present we shooed it out. Later Valery Babanov, twotime Piolet D'or winner, stopped by our tent on his way down. He

and his partner Fabrizio Zangrilli were trying to climb a new route

on Mt. Hunter, and were acclimatizing on Denali. Alexey turned

out to know Fabrizio from Peak Lenin, so he stayed and talked.

The next day we awoke to much better visibility and we

left around 9:30 am for the 11000' camp. Though it was possible

to go without using my snowshoes, I thought I would feel pretty

embarrassed if I didn't use them at all during the expedition so I

pulled them out. It turned out to be the only section on .the

mountain where I used them. It was sunny at 11000' and at potnts

we were even walking around in our T -shirts. Up to that point we

were using sleds, but now that it had gotten steep we would be

using double carries. We took some gear and headed out to make a

cache above Windy Corner at around 13500'.

Visibility remained good when we left around 12:30 pm,

rh our backpacks were much heavier than the night before so

'idn't go as fast. There were many other parties at the I 4200'

· when we arrived: Japanese climbers taking group pi

22

~.H

uleir sponsor's flag, rangers' weather forecast tents,

several commercial expeditions. It was pretty cold; durin£.,

night I slept in a down vest and used toe warmers. That night the

altitude had begun to affect me and I had a clenching headache. I

couldn't fall asleep until 5 am, and then I only dozed off after

taking paracetamol.

Even with the painkillers, my sleep was poor and I still had

a headache and felt weak when I awoke the next morning at 10 am.

Though still acclimatizing, we took a trip to the West Buttress

ridge. The steeper section of the headwall had fixed ropes with

angles at some points reaching 60°. Though it was not physically

tiring, my headache matched with the lack of oxygen made the

three-hour climb challenging. Alexey's liver was giving him pain

from a recurring illness so Dima and Zulfiya went ahead to the

17200' camp and left their cache while Alexey and I turned around

near Washburn Thumb and left our loads there. That day I took

several ibuprofen tablets, but my headache did not subside. In the

evening a group of Russians from Vladivostok (Vladimir Markov,

Komsomolsk-na-Amure, Sergey Kopylov, and Andrey Gilev)

arrived who were also headed up the West Buttress route.

When I got up the next morning I didn't feel any better than

the day before. We left the smaller tent at 14200' and trudged for 3

hours to get to the ridge. Just before we reached Washburn Thumb,

Dima's crampon got caught on his pants and he started sliding

down. Fortunately, he was able to self-arrest; had he been a few

meters ahead where it was considerably steeper he would have

been in a lot more trouble. Even after arriving at the 17200' camp,

my headache continued to throb. I couldn't fall asleep until 5 am,

so going up the next day was out of question. The others headed up

for Denali pass in the morning, though they turned back at about

18200' as a result of heavy weather. By nightfall I felt somewhat

better. Many parties arrived at the camp that night, as the weather

forecast was good for the next day.

..

JWing pages:

1ker and 14,200' camp from headwall- Dmitry Shapova/mJ

nber on the West Buttress- Dmit1y Shapovalov

23

Dima, Zulfiya and Alexey went ahead of me since they

were more acclimatized. We didn't rope up on the traverse, as we

didn't have enough pickets for running belays. The route cut across

the 30° slope and gained about 1000 feet before Denali pass. From

this point the route followed a gradual but large plateau until the

summit ridge. The visibility was poor and it was windy but the

wands were visible. It took me 6 hours to get to 19700', where 1

met Alexey and some others headed down. I wasn't as exhausted

as before and was sure that I would summit that day. The

guidebook was giving time estimates at 8-10 hours to the summit

and I had an hour of walking already behind me. Nevertheless,

Alexey thought that I looked tired and might not be able to come

down by myself, so he asked me to go down with him and try to

summit in a day if I felt better. It was a pity to tum back, but I

agreed. I had to be accurate on the traverse during the descent,

since Dima went ahead with the rope; I was careful not to snag a

crampon on my pants.

In the morning the weather turned for the worse and the

forecast for the next day wasn't looking good either. The members

of the Vladivostok team had come to the 17200' camp and had

decided to wait for good weather to summit. After speaking with

them, we decided to descend to the 14200' camp to rest, and then

go up to the summit all together when the weather improved. On

the way down we ran into Ravil Chamgoulov from Vancouver,

who had earned the "Snow Leopard" distinction for summiting the

five 7000m peaks of the former Soviet Union and was now

ascending the West Buttress solo. In the evening he came to our

tent, and we spent lots of time talking and eating. We went to bed

around midnight, and I enjoyed my first fulfilling sleep that night.

Rejuvenated and with promising weather, we headed up to

the 17200' camp to prepare for ascent. On the fixed section I

realized that I had forgotten my ascender at the 17200' campsite

1ad to use a T -block to make it up. At 17200' we had some

dge with salo (Russian bacon, which is more or less 100~ 1 .1-'n+\

26

('limber on a Cornice Below the Summit- Adilet Imambekov

ll1r dinner. My heart rate had improved though my headache had

reappeared.

We awoke to the sun shining for the first day of the

summer, though the cold and windy weather outside didn't seem to

acknowledge it. The wind was covering our steps when we started

and we had to break trail. The traverse had less snow than my

attempt; so we had to front point some sections. On the

part or the traverse the wind was blowing uphill and we had

In \vait I(H· Vladimir who was carrying the rope far behind us. At

point, most other climbers were turning back After Sergey

I went down to Vladimir and asked if we should go down,

27

but he ~·efused and gave me the rope. Looking at him and the others

ascendmg at a slower pace, I decided to give it one more try.

By the time I was on the pass again, the wind had subsided.

I. headed up with ~ndrey after briefly stopping to warm up my

nght foot (by pounng some tea from my thermos on it). Later 1

realized that my right liner

didn't have an insole,

though it had never posed

a problem during training

in the White Mountains.

On Football Field we had

snacks, and I left all of my

belongings except for my

ice axe and camera. It took

an hour and a half to get to

the summit and close to

the top I had to take three

breaths for every step. We

had triumphed!

I slept very well

after the summit and got

Kazakhstan on the Sunu11it!

up late, meandering my

- Courtesy Adilet Imambekov

way down to the 14200'

campsite. After a few hours the others caught up. The day before,

while taking off his gloves to fix his crampons, Sergey had

frostbitten his fingers and toes and we brought him to the ranger

station just to make sure it was nothing serious. Around 1Opm we

hiked for two hours down to the 11000' camp.

Our final morning on Denali I awoke nice and late to warm

and sunny weather. It took 4.5 hours to get to Kahiltna Airport. It

was even warmer and sunnier at the airport, and for the first time in

two weeks I took off my socks and liners, changed my T -shirts and

lown on the Thermarest relaxing in wait for the plane. That

noon I flew back to Talkeetna and had the best bee·· "~'"-!

wich of my life.

28

How to Climb a Stream

Takashima

Sawa-nobori and its history

Climbing a stream? I suppose many people would wonder

exactly what such a past~me i.s. c.limbing ~ stre~m, or, as v:e ~all

, ~· twa-nobori, is a valid chmbmg style JUSt hke rock chmbmg

lt ' t

.

1

k

;md ice climbing. In the. old days, mou~tams

were a p ace to rna e

living as well as obJects of worsh1p. Loggers, hunters, and

herbalists all made their way into the mountains as part of their

trade.

About a hundred years ago, alpinism was introduced as a

in Japan. Mountains, or more precisely ridges and walls,

became prime climbing objectives. Unfmiunately, Japanese

climbers could not find rocks and walls everywhere. Unlike the

Alps, Japan's mountains are mostly covered by trees and grass.

Climbing bushy ridges requires a great deal of effort (and is not

fun at all). Naturally, some climbers turned their attention to

streams, which were abundant in Japan. During the golden age

of climbing, sawa-nobori was perceived as pseudoalpinism and

pursued rather unwillingly. But now, climbing has become

diversified, and more and more people enjoy sawa-nobori.

Cicar

Most climbers dislike being wet. Being wet means death

in certain situations. Sawa-nobori, however, reverses the

normal relation between climbing and wetness. In sawa-nobori,

being dry is abnormal. This paradigm shift opens up a whole

new climbing field, with its own specific gear requirements. Since

practitioners are always wet, they must take care to choose

d(~thing. Like most modern technical clothing, it should dry

qmckly and should be warm even when wet, such as traditional

or more modern polypropylene and fleece.

The most important thing is footwear. Traditionally,

thi (traditional split-toed heavy-cloth shoes) and waraji

lll'illg j)(tges:

versing to the base of the climb- Courtesy Ko Takashima

hout a paddle - Courte.sy Ko Takashima

(straw sandals) were used. Now, most people wear water shoes

specially made for sawa-nohori. These shoes don't slip on wet and

slimy rocks and the soles are made of polypropylene.

Additionally, gear must be reduced to a minimum. No one

wants to swim with a heavy pack. We don't bring stoves; there is

plenty of firewood. We don't bring water either; there is plenty of

it, too! Some people only bring rice and salt. Fish and edible wild

plants are abundant. Tents and sleeping bags arc also

unnecessary. A piece of tarp and a sleeping bag cover arc

enough. The most annoying part of sawa-nobori in Japan is

dealing with insects, such as mosquitoes, horseflies, and leeches.

Nets and insect repellant are useful but the only real way you can

avoid insects is to embrace the water. In Holdcaido, you also

have to think about bears. All in all, simple is best and the lighter

the better.

3. Techniques

Savva-nobori has its own rating system just like rock

climbing. There are six grades (1-6), based on factors such as

length, continuity, and commitment. Some climbing techniques

are unique to sawa-nobori. Waterfalls are, of course, the biggest

obstacles. We have two options; to climb them or to avoid them.

Climbing waterfalls is fun, so we try to climb as far as we can. If

the stream is large or swollen, it is dangerous to climb in it, so we

climb the sidewall of the waterfall. The sidewall is not always dry

and protection is poor in most cases. When you can't climb

either the waterfall or the sidewall, you advance around them.

Sometimes you have to climb rocks, and sometimes you have to

climb bushy ridges. If you have to climb kusatsuki and

dorokabe, you are really in trouble. These are steep walls of

mud with grass (kusatsuld) or without grass (dorokabe). You

should bundle as much grass as possible, push it down, and slowly

b with your feet nailed in the mud (the split toes of Jikatabi

· you leverage in the mud). Kusatsuld is ve1y slippery, ~

:to climb carefully. To climb dorokabe, you need to giv(

32

-~~-·., ..... d feet traction with a suitable tool, such as an ice axe

oth cases, protection is extremely poor. And the final sectior

1e stream is yet another obstacle! If it is grassland, you are

1cky. Often, however, dense bushes are waiting for you. It may

tke hours, or if you are unlucky enough, a day to reach the path

nd the way back to civilization.

If you are interested in sawa-nobori and have a chance to

orne to Japan, I would be willing to guide you. It would be my

leasure to help as many people as possible get to know about

awa-nobori and enjoy it.

edral, sawa-nobori style - Courtesy Ko Takashima

Ten on the Hat

Andrew Richardson, Craig Sovka and Matthew Richardson

To celebrate Pony Boy's long-awaited engagement and

imminent wedding, a group of intrepid Banditos assembled in

southern Utah for Lad's Weekend 2003. This was the sequel to the

infamous Lad's Weekend 2002 (in honor of Hot Legs' upcoming

wedding), which not only saw 11 gentlemen successfully ascend

the glacier route on Mt. Daniel (7960') in the Washington

Cascades, but also set new standards for backcountry extravagance

(smoked salmon, prosciutto and olives, a wheel of brie, and ten

liters of red wine!). Vast quantities of claret once again procured,

the Lads were ready for some real desert adventure: an ascent of

the Mexican Hat, a bizarre sandstone formation just north of'

Monument Valley.

Though half of the jokers there for the climb didn't know a

jumar from a Jagermeister, the AO-rated route (which involved

aiding through a large roof via a rusty bolt ladder placed sometime

around the middle of the last century) went more or less without

incident. Some members of the gang doubted the structural

integrity of the tower, but the Team Geologist assured one and all

that since it hadn't tumbled yet, it wasn't likely to tumble in the

next hour or two. By noon our summit on the summit was

underway, and the entire Fellowship was ready for victory shots

from a bottle of Herradura Afiejo. We left a number of offerings to

the Gods to ensure that the tower would remain standing for at

least a few more years.

This was the sixth ascent of the Hat by Muddy Water, and

Pony Boy's fourth ascent. Other outlaws witnessed there and

known only by their aliases included Hot Hot Papa, China Girl,

Shotgun Willie, and the reticent Cowboy, among others.

34

Mexican Hat- Andrew Richardson

:Aid climbing up the roof- Andrew Richardson

lC

litnbing partner Janet is an energetic grad student who

in ~ lab across the hall. At one point I had mentioned that

looked very athletic; she replied that s.he thought she looked

like a ballet dancer than an athlete. L1ke a ballet dancer, she

rnotivatcd and works herself hard, but like a climber, she tends

that everyone around her is grossly overworked and plays

little. We both believe that we were doing good by

the other to hit the rocks. "You going climbing this

she asked.

1 wasn't actually planning on climbing; Saturday was a day

lab, and Sunday was a trip to the Harvard Mountaineering

cabin on Mount Washington, a work trip to shovel shit out of

outhouse. But fall in New England is the best time of year, and

would be a shame to spend such a beautiful day working. "Yes,"

1

''I'll meet you here at seven."

On the drive up, I developed the unholy thought of hauling

up Recompense. Janet is fearless, and even though she's less

she will follow anything I can lead. Recompense is a

classic route at Cathedral Ledge that I had been wanting

do. As a sustained 5.9, it was a half-grade more difficult than

I had led before, but I had been leading 5.8+/5.9- at the

in a previous weekend; I felt confident enough to take the

end of' the rope on Recompense.

It was a perfect day for climbing; sunny and cool, with the

showing their full colors. Janet didn't feel great at first so

tried an easier route, aptly named Funhouse. We scaled it with

el:f(Jrt, and headed with confidence up a series of ledges to the

of Retaliation, the sister climb to Recompense that was a solid

4

), hut less sustained.

Retaliation turned out to be an enormous right-arching

or !lake. The rock became very steep and seemed to fall

1

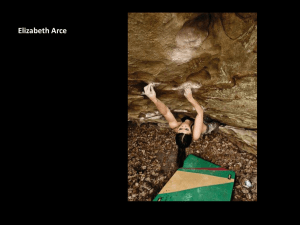

Brewster enjoying New England ice- Laura Fox

37

away from the cliff face to the right of the flake, exposing a

hundred-meter drop to the valley below. It was beautiful and

daunting. Two climbers were ahead of us on Retaliation. The lead

was a tall, lanky man around twenty. His belayer was a shorter

man in his thirties, with a deep tan and a short beard. The team

looked strong and experienced, and I expected them to be well

beyond us by the time I had racked gear onto my harness and

arranged a belay.

I started up the easy first pitch just as the leader of the party

ahead of us statied on the second crux pitch. To my surprise, the

leader was having difficulty. He placed a great deal of protection in

the crack, and struggled at every move. He finally called "take,"

and hung from his last piece of protection, resting until the burning

in his hands and forearms subsided. After a long break he tried

again, but still could not make the strenuous move over a bulge. He

gave up and called for his partner to lower him.

Janet and I dangled uncomfortably from our makeshift

stance, getting colder while growing progressively restless and

intimidated. The older man struggled as much as partner, but with

pre-placed protection, he was able to progress more quickly. He

hesitated several times at the bulge and hung on the rope. Finally

he got an undercling, worked his right foot level with his

shoulders, gave a tremendous heave, and stepped up into a tiny

alcove. He rested awhile, then finished the easier climb to the top.

I didn't want to abandon the climb, but it now seemed

tougher than it had initially appeared. We discussed going for

something easier. Janet wasn't sure she could make it up in. her

present state, and I was afraid it would take all the concentrat~~n I

could muster. But given our achievement-oriented personalities,

we would have been disappointed if we had bailed without even

trying.

I began to map the placement of protection, to rehearse the

1ence of moves for getting past the difficult parts. I dipped my

aty hands into a bag of chalk, affirmed that I was on belr" ,,rJ

off. It was strenuous and awkward, but the handhold

38

d the placement of protection was straightforward. Gi

an

· · 1y easy. I c1'1mb ed qmc

· 1 ..

expectations, it was surpnsmg

'. • g my strength and placing gear every ten feet. I placed a

~onseiV 111

'*'

ieee of gear, rested a moment, and pulled passed the bulge

p1inimal effort. I was very pleased with myself as I stepped

t~e tiny alcove above, two solid pieces of protection at my feet

elatively easy climbing above. Looking down at Janet, I could

:hat see that she was also pleased; in ten minutes, we had

su assed what had taken our predecessors over an hour.

~ rp Moving out of the alcove would be difficult; the rocks were

with seepage, and the adhesion of skin and rubber to wet rock

unpredictable, as is the stability of protection. There were two

up from the alcove; the path to the right was extremely wet,

the path directly above was drier but overhanging. I made for

overhang, which appeared to lead to a large, dry handhold after

single move. To my surprise, the "handhold" was actually a

l$loped, narrow lip that would take no hand at all. With nowhere to

and nowhere to go, I called for Janet to "watch me" as I

scuttled back to the alcove.

I looked back up at the overhang above me and

contemplated strategies to overcome it. The worst-case scenario I

could imagine was taking a clean fall onto reliable protection.

to get on with it, I started again on the overhang without

rl:covering complete strength in my hands and forearms.

Two moves up, I could tell that I would fall. I realized then

if I had rested just a little more, I could have used brute force

lo mantle onto one of the tiny ledges, but I was just too tired. I

nevertheless attempted this maneuver, and had nearly gotten my

on the ledge when I knew that I had to let go. I called for Janet

lo "hold" as my fingers melted off the rock. It seemed a long time,

nllhough in actuality I fell no more than five meters. The rope was

taut at the cam, and I sat there dangling, dazed, and

-·"""""'~" to have failed. I called to Janet that I was fine.

l ~vas determined to finish the climb. I looked at the rightext! from the alcove, and realized that despite the

39

condensation, it was the smarter route. I reached out and grabbed

the rock, pulled myself to it, and realized by the third move that I

had either sprained or broken my ankle on the fall; I could bear no

weight on my left foot.

Despite my tough exterior, I had to say, "Uh, Janet, I uhh,

well, I'm really sorry, but I think I'm hurt. Uh, I don't think you're

going to get to do the pitch. I'm sorry. Uh, yeah, I don't think I can

finish here. Maybe ... Owww, shit! Right, yeah, I can't put any

weight on that foot. Sorry." Janet was clearly worried and assumed

the worst. My priority was to get down, and I clipped directly into

the cam that held me, focusing hard through spasms of pain. I had

just started to rig a rappelling anchor, but our friends who had

preceded us on the climb came down just then.

One of the best parts of climbing is the generosity between

climbers, and their kind treatment was no exception. They handed

their ropes to me and I descended on them, hopping on one foot

and collecting the gear I had placed on the way up. They helped us

down the final rappels and escorted me down the trail to the car.

As a final gesture, they offered me two codeine tablets from their

first aid kit.

Lab work was difficult for a while. I was getting around on

crutches at first, but soon discovered that hopping on one foot was

surprisingly efficient. I could get around at the speed of a slow run,

carry my own things, and open doors. My ability to compensate

was noted by my Russian lab mate, who observed my

resourcefulness at the ice machine. I was supported on one leg,

with the injured foot extended behind for balance; my arms

extended over the ice machine to fill a bucket. "Oh man!" he

remarked. "You are like, what you call...you are like ballet

dancer!"

40

e, Last Winter

atie Ives

___ u .....

) paint a white rose, you use every color but white. The

ghlights on the tips of the petals are yellow, the shadows blue.

ut the center of the rose is an icy green

epping into the Flume is like stepping below the day. You look

'to see the sun touching the over-hanging branches of the fir

~es, to see bright yellows and deep forest-greens.

side the Flume, there are only the colors of rock and ice and

ladow.

1e frozen waterfalls hang in intervals, chords of pale green and

ue light. Some are staircases of icicles, layer upon layer of

mging crystals, chandeliers that shatter, as each cramponed boot

rikes, searching for a solid hold.

:inerals collected from the earth, from rocks, carried by the once)Wing rainwater, give the ice an ochre hue. Sometimes ice takes

·ganic forms, resembling primitive plants, mushroom growths,

ant spores.

ce," the climbers shout, as each pounded note of the ice-tool

nds a flurry of loose shards chiming against each other. Much

e falls; the call becomes redundant. The pieces, striking the

~lmets, the legs, the hands ofthose below, are sharp but soon

~rgotten. The next flurry falls.

:trger blocks of ice lie piled against the cliff bottom like giant

tessmen swept off a board, like broken, translucent pillars.

~'-~~1-:d

from the rock, a cylinder of ice, fluted marblel ochre and green, hangs three feet from the ground; an

41

aerial Grecian column. Half of the column falls, with a heavy blow

of the boot. The climber dangles, swears, then drags herself

upward.

A fallen man crouches on the snow, hand pressed to forehead.

Two men lean over him; one places his hand on the man's back;

the other stands, hands in pockets. All three stare at the widening

circle of red on the blue-white snow. There is no movement.

In patches, the water trickles between the icicle forms, as though

the wall hummed with hidden life. Water sprays the face of the

climber, coats his gloves and freezes; the climber has become a

part of the waterfall.

"Are you ready to come down?" The belayer stands with bare

hands raw from the wet rope, feet braced against the snow, in the

cool depths of the chasm. But the climber above hangs silent from

numb wrists and stares through the green heart of the ice, until

there is no more color, nothing more to see.

In the blue twilight, the moon idles across the frozen riverbed,

tracing bluish glyphs in the rippled ice-a glass sheath over the

rushing water. The climbers make a slow procession up the valley

path, below silhouettes of mountains. They attach headlamps to

their helmets, like miners.

Overnight, the ice renews itself; drip by drip refreezes.

42

~~·~:=:er's

History

Tilliam Lowell Putnam

I entered Harvard in the fall of 1941, at the insistence of my

·eat-uncle, Lawrence, two months before my 1ih birthday. Soon

flunked English A and had to take a remedial writing course.

his time I had a much more sympathetic instructor who asked me

' write about something I cared about. That was the mountains. I

)t a much better grade and became a sophomore.

Then I became 18 and there was a war going on. Hemy

all, Ken Henderson and Andy Kauffman (all now deceased, and

1 past benefactors of the HMC) wrote one each of my necessmy

.ree letters so I would be sure to get into the Mountain Troops,

.en forming at Camp Hale in Colorado. I celebrated, if that's the

ght word, my 19th birthday in Kiska, Alaska. But then things got

~tter; we came home and I was sent to Officer Candidate School

,t the fmmer Benning School for Boys). I celebrated my 20th

rthday by being assigned to Company L of the 85th Mountain

tfantry as weapons platoon leader. Before I could celebrate my

1st birthday, I had stopped a piece of German shrapnel with my

ght lung - here went K2, etc. - and ended my army days with

~veral decorations and as L Company's commander.

Back in college in early 1946, I put a notice in the Crimson

1d revived the HMC, declaring myself its president. The next

tmmer I co-led, with Andy Kauffman and Mal Miller, the club's

~46 Expedition to Mt. St. Elias- evetyone goes there, now, but it

as a big deal in those days.

A few years later, Ken Henderson got me interested in the

ppalachian Mountain Club, of which he was then President; I

~came its Corresponding Secretary and looked around for people

1 make Honormy Members, etc. I set up their leadership training

1d certification program and got involved with several mountain

:scues in the White Mountains. You meet real people on those

·~~+n

great fish cops like Paul Dohetiy and Willie Hastings, and

angers like Ken Sutherland and Rick Goodrich. On its

43

centennial year, the AMC elected me as one of those thine,~.

Then Henry Hall and Carl Fuller asked me to beco

editor of the American Alpine Club Guidebooks for West

Canada. I had stayed with those mountains because I could af£

trips there, and because I couldn't consider high altitude with

lung. By my 30th birthday, I had learned a great deal about th

hills and had accumulated a great many friends in Canada. 1

task Hemy had in mind was a real challenge: to follow in

footsteps of scholarly giant Dr. Roy Thorington. UnfortunatE

Roy and I got along poorly. I was young and brashly aware t

backpacking was a superior method of bushwhacking to

beloved horse packing, but I loved and respected him.

Later President Kennedy appointed me to the Natio1

Advisory Commission for the United States Forest Service. T

was real fun; I had some influence regarding policy tow<

recreational users of the mountains - until Richard Nix

unappointed me. In 1968 Nick Clinch asked me to join the Bm

of the AAC and when no one else wanted the job, I became

president in 1974. Soon my mountaineering guru, Fritz Wiessn

suggested that I evaluate the merit in the AAC staying active in t

International Association of Alpine Societies (UIAA), and so

took me to a Council meeting in Geneva. Then he asked me to .

climbing with him at the Baou de St. Jeannet, where he invited r

to dinner at a fancy place and told me that he wanted out and tha

should assume the job of representing American mountaineers

the world body. So I did - for the next thirty years. Along t

way, I became pretty well known as a mountain person; doi1

daily editorials on my TV station in Springfield, MA didn't hl

my reputation- but some of my fan mail might have.

People ask me, since I'm so well known as a climber,

I've ever been up Mt. Everest- "No!" Damn that shrapnel, but

does give me a magnetic personality (which is fine, until you con

+~ those things in airports). Then they want to know if I've ev

imbed the Matterhorn. Gotcha, there; I tell 'em "No, l---L n

oked down on it from the Monte Rosa." That shuts 'em1

44

__,aulll

Report

The cabin is a continuing source of adventure for the HMC.

n November 2003, a party of fourteen HMCers went up in order

o put the cabin aright before the season, which included thenreshman Josh Neff taking a dip in the nether regions of the

mthouse. A small army of caretakers traded off shifts that season

mtil February 2003 when the HMC's own George Brewster took

>ver, finishing out the season with a record length snot-sicle (Notes

rom Cambridge, Spring 2004). Members of the club also spent

ntersession using the cabin as a base for winter climbs and hikes.

This year, a work party found the barrel underneath the

mthouse knocked over again. Josh was exempted from outhouse

iuty this time, and the rest of us proceeded to build a layer of rocks

mderneath the barrel platform, a truss system surrounding the

Jarrel, and a hook to lock the barrel's cable in place, preventing

novement in all six axes of motion.

Long-term projects under current consideration include re~oofing the cabin (expertise and help of any kind welcomed!) and

[nstalling a larger solar power system for the base radio.

Neff, Lucas Laursen, and John Neil Thompson ponder tl

l'e of the outhouse -Joseph Abel

In Memoriam

Andy D. Martin (1972-2004)

Andy Martin received an AB from Harvard in 1998 in Visual ar

Environmental Studies, cum laude. By then his goals had alreac

turned toward medicine. He worked as an ambulance driver ar

took classes required for medical schools. During the late 199(

his outdoor activities were primarily backpacking and climbing

the SielTas and elsewhere. [See pg. 17 -ed.]

In summer 2000 Andy and a friend were hiking up Mt. Whitm

when he developed a severe nosebleed, which led to a diagnosis c

sinus cancer. One week

later he began medical

school at Tulane but soon

returned to California for

surgery and radiation. He

restarted school in 2001

and completed two years

despite

surgery

and

chemotherapy

for

a

recurrence. His third year

was disrupted by a further

reculTence after which he Andy, Mike Dewey, and Mark Roth'

devoted his energy to Memorial Hall - Courtesy Mike Dewj

studying his own rare

cancer in a Tulane lab. A third recurrence this fall caused his deat

During periods of recovery from treatments he took many wall

with friends and family. Among his favorite places were tl

Buttermilks near Bishop CA, where he worked up to v

bouldering routes. He also tried sea kayaking, surfing, ar

explored Peru, China, and Costa Rica.

S(

For

more

about

his

battle

with

cancer,

ww. bounceforlife.org.

-Do

46

~.._,utuership

of the HMC

?cords of membership have not descended intact to the current

ricers. Starred names are !mown bad addresses. Please direct

'rrections to mountain@hcs.harvard.edu or The Harvard

ountaineering Club, F' Floor University Hall #73, Cambridge,

A 02138.

fe and Alumni Members

>rons, Hemy L. 3030 Deakin St Berkeley, CA 04705

nes, Edward 2 Spaulding Lane Riverdale, NY 10471

nason, John Department of Geology Stanford University Stanford, CA

94305-2115

senault, Steve 5 Tilden St. Bedford, MA 01730

kinson, William C. 343 South Ave. Weston, MA 02493

rrett, Dr. James E. 10 Ledyard Lane Hanover, NH 03755

al, William D. P.O. Box One Jackson, NH 03846

nner, Gordon P.O. Box 5027 Berkeley, CA 94705

rnbaum, Ed 1846 Capistrano Berkeley, CA 94707

auner, Jeanne* 11 Fallon Place #9C Cambridge, MA 0213 8

ataas, Arne* 2 Ware St. Apt.# 309 Cambridge, MA 02138

iggs, Winslow R. and Ann M. 480 Hale St. Palo Alto, CA 9430 I

own, Richard McPike 490 Estado Way Novato, CA 94947

own, Wil 13 Williams Glen Glastonbury, CT 06033

11lough, Per Molecular Biology and Biotechnology University of Sheffield

Sheffield, UNITED KINGDOM

llaghan, Haydie 22 Ashcroft Rd Medford, MA 02155

rman, Ted 8 Chestnut Park Melrose, MA 02176

1ter, Madeleine 5036 Glenbrook Terrace, N. W. Washington, D.C. 20016

1amberlain, Lowell 12 Pacheco Creek Dr. Novato, CA 94947

:~rk, Brian Edward* 700 Huron Ave, 14C Cambridge, MA 02138

1bb, John C.* P.O. Box 1403 Corrales, NM 87048

1chran, Nan 233 Ash St. Weston, MA 02193

'llins, Lester A.* 1415 Thompson St. Key West, FL 33040

'ombs, David 528 E 14th Ave Spokane, WA 99202

,x, Rachel 2946 Newark Street, NW Washington, DC 20008

onk. Dr. Caspar 8 Langbourne Ave. London, N6 AL ENGLAND

wid* P.O. Box 823 Cambridge, MA 02142

47

Daniels, John L. 39 River Glen Rd. Wellesley, MA 02181

Deny, Louis* 132 Crescent Place Ithaca, NY 14850

Dickey, Tom 1570 Granville Rd. Rock Hill, SC 29730

Drayna, Dennis T.* 536 Fordham Road San Mateo, CA 94402

Dumont, Jim RR 1 Box 220 Bristol, VT 05443

Durfee, Alan H. 28 Atwood Rd. South Hadley, MA 01075

Eddy, Garrett 4515 W. Ruffner St. Seattle, WA 98199

Embrick, Andrew Valdez Medical Clinic P.O. Box 1829 Valdez, AK 99686

Epps, Dean Archie* 4 University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Estreich, Lisa* North House M308 Cambridge, MA 02138

Ferris, Benjamin G. Box 305 10 Town House Rd. Weston, MA 02193

Field, William B. Osgood* P.O. Box 583 55 Hurlbut Rd. Great

Barrington, MA 01230

Flanders, Tony 61 Sparks St. #3 Cambridge, MA 02138-2248

Forster, Robert W. 2215 Running Springs Kingwood, TX 77339

Freed, Curt 9080 East Jewell Circle Denver, CO 80231

Gabrielson, Cmi Student Canter 461 Massachusetts Institute of

Technology Cambridge, MA 02139

Gehring, John 63 Maugus Ave. Wellesley Hills, MA 02481

Goody, Richard* P.O. Box 430 Falmouth, MA 02541

Graham, William Office of the Dean 45 Francis Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138

Green, Dr. Peter* Caltech 138-78 Pasadena, CA 91125

Gucker, Frank F.* 392 Great Rd., Apt. 302 Acton, MA 01720

Hamilton, Scott D. 3304 Hill Rd. Little Rock, AR 72205-4108

Hamlin, Julie Meek P.O. Box 506 Southpoti, CT 06490

Hartshorne, Robert 768 Contra Costa Ave. Berkeley, CA 94707

Hightower, Prof. J.R. 2 Divinity Ave. Cambridge, MA 02138

Hoguet, Robert L. 139 E. 79th St. New York, NY 10021

Hoover, Win 1240 Park Ave. New York, NY 10028

Houston, Charles S. 77 Ledge Rd. Burlington, VT 05401

Imbrie, John Z. 21 Pembroke Dr. Lake Forest, IL 60045

Jameson, John T. 1262 La Canada Way Salinas, CA 93901

Juncosa, Adrian M. Harvard Forest Petersham, MA 01366

Kellogg, Howard Morgan 51 Ivy Lane Tenafly, NJ 07670

Koob, John Route 113 P.O. Box 101 Silver Lake, NH 03875

Lehner, Michael* 2 Brimmer St., #2 Boston, MA 02108

Levin, Philip D. 10 Plum St. E. Gloucester, MA 01930

Lewontin, Steve 107b Amory Cambridge, MA 02138

r ~.g, Alan K. * 4 Old Stagecoach Rd Bedford, MA 01730

ntel, Samuel J. 608 Flagstaff Dr. Wyoming, OH 45215

rgolin, Reuben 3 Sacramento Ave Cambridge, MA 02138

tthews, W. V. Graham Box 381 Carmel Valley, CA 93924

48

. ·t 1. RobertS. P. 0. Box 8916 Rancho Santa Fe, CA 92067

McUII e'

.

d

, til Michael P.R. 448 Barretts M1ll R . Concord, MA 01742

MeGra •

ohn 5 Maya Lane Los Alamos, NM 87544

tvfc Leo d, J

.

Karen* 2399 Jefferson #18 Carlsbad, CA 92008

Messer,

·I'll,. Maynard M. 514 East F'Irst St. M oscow, ID 8 3 843

'lv!CI,

r .

Lawrence* 894 Weston R d ., Apt. #lA··d

.cu· en, NC 28704

ty,mer, ·

.

,

t

Marcus*

Seaside

850

Baxter

Blvd.

Portland,

ME 04103

1

11

'

1v,or o ,