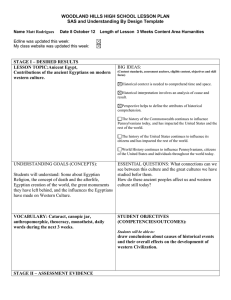

Get cached

advertisement