Assessment: A Literature Review

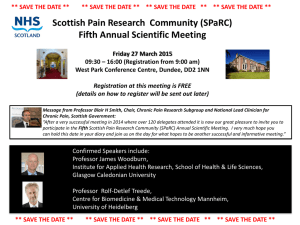

advertisement