REVIEW

doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03621.x

Alcohol consumption and the intention to engage in

unprotected sex: systematic review and meta-analysis

of experimental studies

add_3621

51..59

Jürgen Rehm1,2,3, Kevin D. Shield1,2, Narges Joharchi1,4 & Paul A. Shuper1,5,6

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH),Toronto, Canada,1 Institute of Medical Science (IMS), University of Toronto,Toronto, Canada,2 Dalla Lana School

of Public Health (DLSPH), University of Toronto,Toronto, Canada,3 Department of Statistics, University of Toronto,Toronto, Canada,4 Department of Psychology,

University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada5 and Center for Health, Intervention and Prevention, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA6

ABSTRACT

Aims To review and analyse in experimentally controlled studies the impact of alcohol consumption on intentions to

engage in unprotected sex. To draw conclusions with respect to the question of whether alcohol has an independent

effect on the incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Methods A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies examined the association between

blood alcohol content (BAC) and self-perceived likelihood of using a condom during intercourse. The systematic review

and meta-analysis were conducted according to internationally standardized protocols (Preferred Reporting Items for

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: PRISMA). The meta-analysis included an estimate of the dose–response effect,

tests for publication bias and sensitivity analyses. Results Of the 12 studies included in the quantitative synthesis, our

pooled analysis indicated that an increase in BAC of 0.1 mg/ml resulted in an increase of 5.0% (95% CI: 2.8–7.1%)

in the indicated likelihood (indicated by a Likert scale) of engaging in unprotected sex. After adjusting for potential

publication bias, this estimate dropped to 2.9% (95% CI: 2.0–3.9%). Thus, the larger the alcohol intake and the

subsequent level of BAC, the higher the intentions to engage in unsafe sex. The main results were homogeneous,

persisted in sensitivity analyses and after correction for publication bias. Conclusions Alcohol use is an independent

risk factor for intentions to engage in unprotected sex, and as risky sex intentions have been shown to be linked to actual

risk behavior, the role of alcohol consumption in the transmission of HIV and other STIs may be of public health

importance.

Keywords Alcohol consumption, HIV, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, sexual behavior, sexually

transmitted infections, unprotected sex.

Correspondence to: Kevin D. Shield, CAMH, 33 Russell Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2S1. E-mail: Kevin.shield@utoronto.ca

Submitted 24 January 2011; initial review completed 29 April 2011; final version accepted 15 August 2011

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use is associated with the acquisition of human

immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency

syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and other sexually transmitted

infections (STIs) [1–4], with one major potential pathway

between alcohol and the acquisition of HIV and STIs

being unprotected sex [5,6]. It has been purported that

the consumption of alcohol can result in disinhibition [5]

and a constraint in cognitive capacity that leads to a focus

on risk-impelling rather than risk-inhibiting cues [7]

which, in turn, can increase the likelihood of having sex

© 2011 The Authors, Addiction © 2011 Society for the Study of Addiction

without a condom. However, this direct causal pathway

linking alcohol use to unsafe sex and subsequent transmission of HIV and other STIs has been difficult to establish conclusively, as there may be confounding due to

personality factors such as sensation seeking, risk taking

or compulsivity (e.g. people who consume alcohol and

then engage in unsafe sex may be doing so because they

have different, riskier personality traits) [8]. The role of

such third variables may, in part, be responsible for the

somewhat inconsistent evidence supporting a behaviorally based alcohol use—unprotected sex association [8].

For example, meta-analyses and reviews based on studies

Addiction, 107, 51–59

52

Jürgen Rehm et al.

assessing the relationship between generalized measures

of alcohol use and/or abuse and the occurrence of

unprotected sex over time (so-called global-level studies)

have provided supportive evidence [1,4,9,10], but these

investigations are typically unable to control for potentially confounding and ‘in-the-moment’ variables [8].

In contrast, meta-analyses and systematic reviews based

on event-level studies, which are able to control for third

variables such as personality traits, have yielded mixed

results, with two meta-analyses finding significant eventlevel associations [1,11] and others finding no significant

associations [10,12,13]. Thus, based on these data alone,

causality cannot be asserted with confidence.

One way to establish causality in such a situation is to

vary exposure experimentally; in this case, exposure to

alcohol. Manipulating alcohol exposure experimentally

for longer time-periods to examine potential disease consequences is both unethical and unfeasible; however,

experimental variation of alcohol exposure is possible for

shorter periods [14,15]. If such experimental variation

can be combined with the measurement of an outcome

which is a valid precursor to unsafe sex, causality could

be established, following the tradition of nutritional epidemiology to establish causality of nutrients for cancer

[16] or in the cardiovascular disease area (see: http://

www.who.int/nutrition/topics/5_population_nutrient/

en/index.html). For example, to show that certain

nutrients can causally impact coronary heart disease,

nutrients have been varied for short periods of time in

randomized controlled clinical trials, and then their effect

on blood lipids as a precursor to heart disease has been

measured. Similarly, alcohol use can be varied experimentally to measure the effect on intentions to engage in

unsafe sex, an established link in the pathway to unsafe

sex behaviors and, thus, to acquisition of HIV and other

STIs [17–19]. Experimental studies investigating the

behaviorally based association between alcohol consumption and unsafe sex do so by randomizing alcohol

consumption and assessing the impact on the selfperceived intent to engage in unprotected sex. Despite

focusing on intentions to use condoms rather than actual

condom use behavior, conclusions can be drawn regarding a potential association between alcohol use and HIV

and other STIs, as the literature clearly shows a significant link between condom use intentions and actual use

of condoms under a variety of conditions and circumstances [17]. Furthermore, intentions have been shown

to be one of the strongest predictors of subsequent

condom use behavior [17].

To exclude the potential effect of personality variables

and to establish an independent effect of alcohol consumption on subsequent sexual behavior, we performed

a systematic review and a meta-analysis of randomized

controlled studies to establish a quantitative estimate of

© 2011 The Authors, Addiction © 2011 Society for the Study of Addiction

the effect of alcohol consumption as measured by blood

alcohol content (BAC) on self-perceived intentions to

engage in unsafe sex, including establishing a dose–

response relationship to assess if alcohol can have a

behaviorally based effect on the intent to engage in unsafe

sex independent of personality factors.

METHODS

The systematic review was conducted and reported

according to the standards set out in PRISMA (Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalyses) (http://www.prisma-statement.org/)[20].

Search strategy and study selection

PsycInfo and PubMed (including MEDLINE and Life

Science Journals) databases were queried for articles

that tested the association between experimental

manipulations of alcohol consumption and intentions to

engage in unprotected sex. Search terms for alcohol were

‘alcohol’, ‘ethanol’ and ‘drink*’. For risky sex, the search

terms were ‘HIV’, ‘sex*’, ‘condom*’ and ‘unprotect*’.

Finally, the search terms for intentions were ‘intention*’,

‘intend’, ‘decision making’, ‘willingness’ and ‘motivation’. Searches of the databases were concluded on 2

May 2011. Articles were restricted to those published in

English on or before the search date. Titles and abstracts

for all references were reviewed, with relevant articles

retained for full paper reviews.

Articles were retained if they met the following

inclusion criteria: (i) consisted of original, quantitative

research published in a peer-reviewed journal; (ii)

involved an experimental manipulation of BAC during

the course of the study; (iii) assessed intentions to engage

in unprotected sexual acts; (iv) tested the association

between BAC and intentions to engage in unprotected

sexual behavior; and (v) involved individual (rather than

group) assessments with participants. To be included

in our quantitative synthesis, articles also needed to

provide a measure of uncertainty for the abovementioned association.

Quality criteria

The minimum quality criteria for inclusion were as

follows: (i) the allocation of placebo and alcohol had to be

randomized; (ii) the participant had to be blinded; and (iii)

the participants had to have not been able to distinguish

between the placebo and alcohol.

Data collection

Measures of association were: (i) linear regression beta

coefficients and their 95% confidence interval (CI);

Addiction, 107, 51–59

Alcohol and intention for unprotected sex

53

P-value; and/or standard error (SE) or (ii) group means

with their standard deviation (SD) for the effect of BAC on

the likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex.

or differed by the sample source (community versus a

campus sample) using a meta-regression analysis.

Measurement of alcohol consumption

RESULTS

The average BAC (if not available, the target BAC) was

used from each study to adjust for individual differences

in body weight. The mean target BAC ranged from

0.03 mg/ml to 0.10 mg/ml. To ensure comparability

between studies, the magnitude of the difference between

means was adjusted for the mean BAC of the intervention

group for each study.

Study selection and study characteristics

Standardization of outcome measures and

measurement of risk relations

As the SD of the self-perceived likelihood of using a

condom during sexual intercourse as indicated on a

Likert scale was not provided for the control groups in

each study, it was not possible to formulate a standard

measure that could be used in the meta-analysis. Instead,

all outcome estimates were corrected for the size of the

scale by dividing each of the estimates by the range of the

corresponding scale.

Differences between mean scores and the SE estimates

for those studies that did not provide a linear regression

beta coefficient were calculated from provided group

means and the SD of these means [21]. In addition, we

standardized risk relations by adjusting all estimates to an

effect for 0.10 mg/ml assuming a linear dose–response

effect. The assumption of a linear relationship was

checked using a meta-regression analysis.

Statistical analysis

Our meta-analysis examined univariate linear regression

beta coefficients by means of DerSimonian & Laird’s

random effects [22]. For studies which provided a P-value

less than an a threshold, a conservative estimate of this

threshold minus 0.001 was taken as the P-value.

The overall point estimate and 95% CI were based on a

weighted pooled measure. Heterogeneity between studies

was assessed using the Cochrane Q-test and the I2 statistic. Publication bias was tested by visually inspecting a

funnel plot for skewed distribution, by using a ranked

correlation test proposed by Begg & Mazumdar, and by

employing a weighted regression test proposed by Egger

et al. [23]. To adjust the pooled estimate for publication

bias we used the trim and fill method [24]. All analyses

were performed using STATA version 11.0 [25].

Sensitivity analysis

We investigated if the association of alcohol and the

intention to engage in unprotected sex differed by gender

© 2011 The Authors, Addiction © 2011 Society for the Study of Addiction

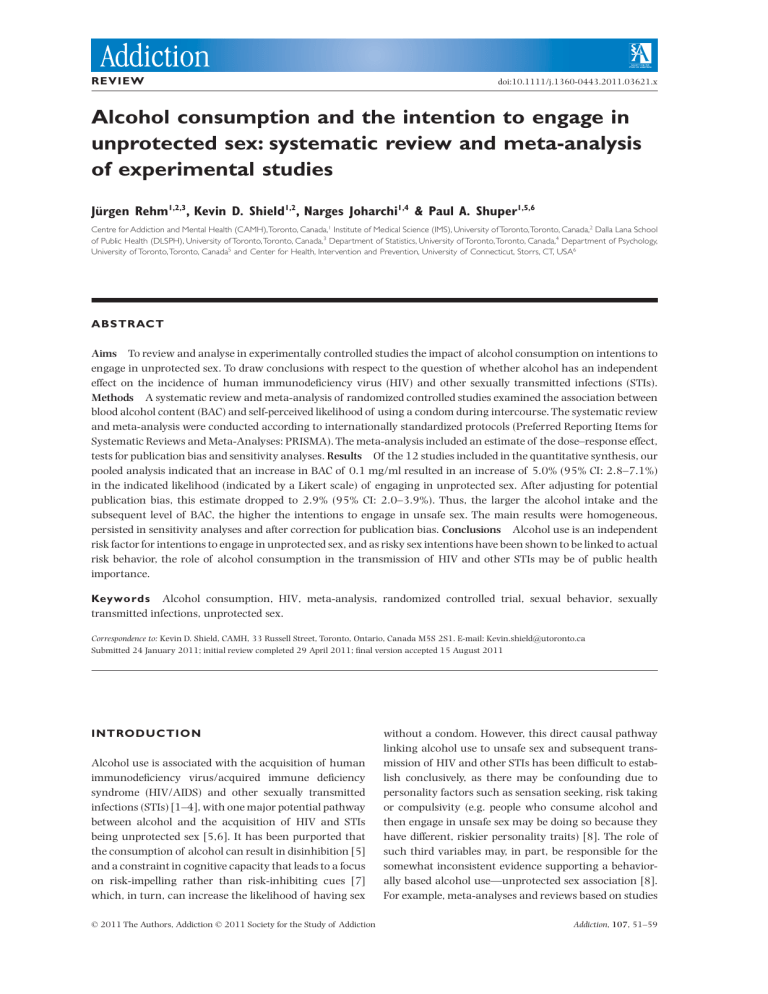

Figure 1 outlines the search strategy. Search results

yielded 631 articles from PubMed and 307 articles from

PsycInfo. Titles and abstracts for all references were

reviewed, and 50 articles were retained for full paper

reviews.

In total, nine publications satisfied the above eligibility

criteria of containing quantitative data relating to the

effects of alcohol consumption on the intent to engage

in unprotected sex where participants were questioned

individually (two papers were excluded for questioning

individuals in groups). Two additional publications that

met the inclusion criteria were found by examining the

reference sections of the 50 relevant publications.

The 11 papers retained for analysis contained a total

of 14 relevant studies. Of the 14 relevant studies, two

involved an analysis of the same participants. Of these

two papers, we retained the paper that examined the

effect of BAC on condom use intentions (the other paper

examined the effect of alcohol dose on condom use intention), resulting in 13 studies. One of the 13 remaining

studies provided a linear regression beta coefficient but

did not provide any indication of uncertainty (e.g. a

P-value, CI or SE) and, thus, was excluded from our

analysis [26]. Of the remaining 12 studies that formed

the basis of our meta-analysis, eight provided differences

between means using linear regression analysis, and two

studies provided the difference between the means as well

as the estimated standard deviation (SD) of each mean.

The remaining 12 studies met all quality criteria and

were retained for analysis. The key study characteristics

and outcomes for the relevant studies can be found in

Table 1.

Definition of intent to have unprotected sex

Measurement of the intent to have unprotected sex was

highly variable across all studies (see Table 1). The constructs and questions also varied in terms of the number

of questions asked, the SD of the measure in the control

groups and the range of the scale.

Meta-analysis

Random effects analysis indicated a significant positive

association between BAC and the intention to engage

in intercourse without a condom, demonstrating that

the higher the BAC, the more pronounced the intention to engage in unsafe sex. Tests demonstrated that

Addiction, 107, 51–59

Jürgen Rehm et al.

Search Result

PsycInfo = 307 PubMed = 631

Articles found by examining the reference

section of relevant articles. n= 2

938 Titles/Abstracts screened

Excluded (including

duplicates) n = 888

50 full- text articles screened

for eligibility

39 articles excluded

n= 38 for not meeting eligibility criteria

n= 1 for analysis of the same participants

11 articles (containing 13

studies) included in qualitative

synthesis

1 study that reported a non-significant effect

was excluded for not reporting a S.E., CI or

P-value

Included

Eligibility

Screening

Identification

54

12 studies included in

quantitative synthesis

(meta-analysis)

Figure 1 Search strategy for randomized controlled trials that assessed likelihood of condom use during intercourse after alcohol

consumption; CI: confidence interval; CI: confidence interval

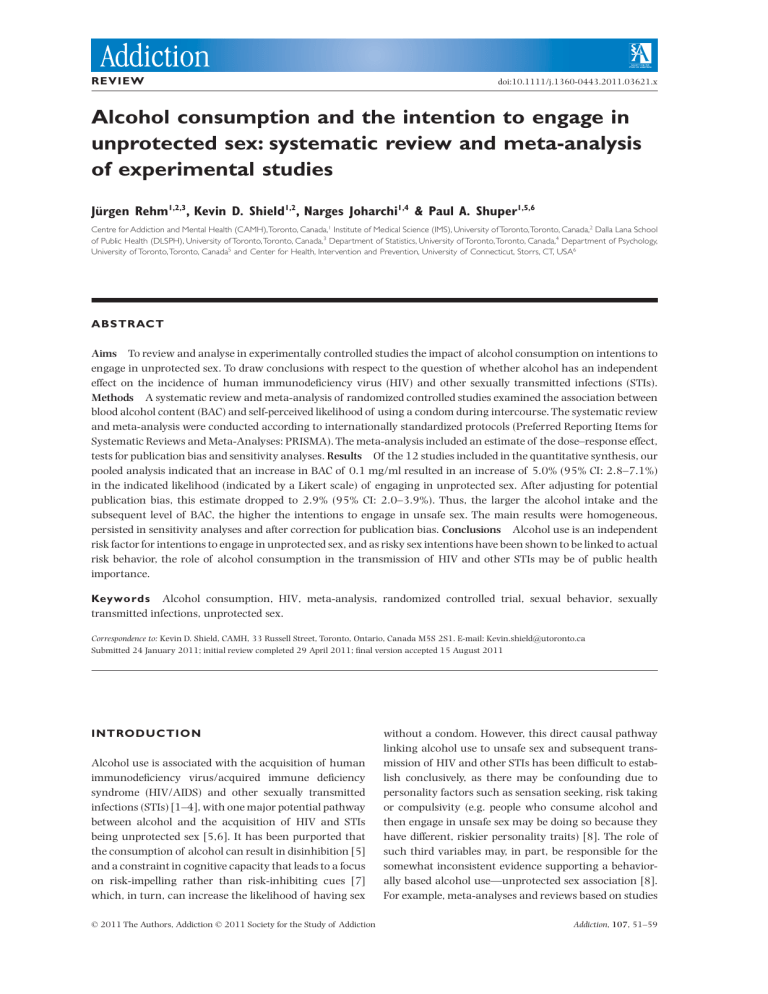

heterogeneity in the estimates was present [Q(11) = 28.52,

P = 0.003; I2 = 61%, P = 0.000]. As demonstrated in

Fig. 2 (forest plot), while all studies showed effects of

alcohol consumption in the hypothesized directions, four

studies had non-significant results whereas the other

eight studies showed a significant association between

alcohol consumption and the intent to engage in unprotected sex. Additionally, all studies had a similar effect size

except for the Ebel-Lam and colleagues’ study [27], which

exhibited the largest effect size. Our pooled analysis indicated that an increase in BAC of 0.1 mg/ml from a BAC

of 0.00 mg/ml resulted in an increase of 5.0% (95% CI:

2.8–7.1%) in the indicated likelihood (indicated by a

Likert scale) of engaging in unprotected sex. Additional

analyses showed that the association between BAC

and intention to engage in unprotected sex was indeed

linear, and the alternative hypothesis of a curvilinear

relationship could be rejected for BAC between 0 and

0.10 mg/ml. Neither gender nor the sample (community,

community and campus, campus) significantly modified

the relationship between alcohol consumption and the

intent to engage in unprotected sex.

Publication bias appeared to be present, as observed in

our funnel plot (see Fig. 3). The funnel plot indicates that

© 2011 The Authors, Addiction © 2011 Society for the Study of Addiction

when plotting the point estimates by the SE of the point

estimate from the studies used in our meta-analysis,

the plot does not take the shape of a triangle which is

expected under the central limit theorem [23,28]. Additionally, the Egger weighted regression also indicated the

presence of publication bias (P = 0.001), while a Begg

rank correlation test did not indicate publication bias

(P = 0.059). These tests indicate that overall publication

bias is probably present and, thus, it is likely that findings

of some studies were not published in peer-reviewed

journals that would have been captured in a search of

the PubMed and PsycInfo databases. Adjustment of the

pooled estimate for publication bias resulted in an

overall pooled estimate of 2.9% (95% CI: 2.0–3.9%) for

an increase of 0.10 mg/ml in BAC from a BAC of

0.00 mg/ml.

DISCUSSION

In experimental studies there is a consistent significant

effect of the level of alcohol consumption on intention to

use condoms, indicating that the higher the BAC, the

higher the intention to engage in unsafe sex. In this study,

we observed that if an individuals BAC increases from 0

Addiction, 107, 51–59

© 2011 The Authors, Addiction © 2011 Society for the Study of Addiction

25.0 (3.8)

24.3 (3.8)

22.7 (2.7)

22.8 (2.2)

23.8

25.0 (3.9)

n = 173 female; USA (campus)

n = 80 male; USA (community)

n = 60 male; USA (community)

n = 48 male; USA (campus)

n = 173 female; USA

(community and campus)

n = 115 (58 female, 57 male);

USA (campus)

n = 79 male; Canada (campus)

Maisto et al. 2004 [49]

Norris et al. 2009 [51]

3

1

2

George et al. 2009 [46]

Kruse et al. 2005 [47]

Kruse et al. 2005 [47]

aMean

blood alcohol content (BAC) levels. bTarget BAC levels. SD: standard deviation.

Schacht et al. 2010 [53]

Ebel-Lam et al. 2009 [27]

Stoner et al. 2007 [52]

2

George et al. 2009 [46]

n = 64; USA (community)

22.4 (2.9)

n = 200 (99 female, 101 male);

USA (community)

n = 61 (30 female, 31 male);

USA (community and

campus)

n = 165 male USA (campus)

Cho et al. 2010 [44]

27.0 (4.0)

20.9 (1.8)

24.9 (3.6)

24.3 (7.2)

24.2 (3.3)

n = 120 (60 female, 60 male);

USA (campus)

Abbey et al. 2006 [26]

Davis et al. 2007[45]

24.0 (3.0)

Sample

n = 180 (90 female, 90 male);

USA (campus)

Substudy

Abbey et al. 2005 [43]

Author

Mean age

(years) (SD)

0.08b

0.079 (0.013)

a

0.034 (0.008)/

0.064 (0.009)a

0.04/0.08b

0.059 (0.011)a

0.05 (0.01)a

0.06 (0.01)a

0.06/0.08/0.10

(mean = 0.08)b

0.06/0.08/0.10

(mean = 0.06)b

0.10

b

0.08b

0.072 (0.010)a

0.069 (0.018)a

Blood alcohol content

(BAC) (mg/ml)

(standard deviation)

Multi-dimensional condom

attitudes scale (MCAS) [50].

Scale 1–7

Condom desire/request; mean of

2 questions [52]. Scale 1–5

Condom desire/request; mean of

2 questions. Scale 1–5

Likelihood of having

unprotected sex (1 Likert

scale question). Scale 1–9

Condom desire/request; mean of

2 questions. Scale 1–10

Intention to use a condom [48].

Scale 0 to 100

Intention to use a condom [48].

Scale 0–100

Likelihood of unprotected sex.

Mean of 4 Likert scale

questions. Scale 1–5

Likelihood of having

unprotected sex (1 Likert

scale question). Scale 1–7

Likelihood of having

unprotected sex (1 Likert

scale question). Scale 1–7

Intention not to use a condom

(3 questions). Scale 0–100

Intention to have unprotected

sex (1 Likert scale question).

Scale 1–5

Likelihood of unprotected sex.

Mean of 4 Likert scale

questions. Scale 1–5

Sexual risk indicator

5.0 (2.2–7.8)

28.8 (17.2–40.5)

4.2 (0.8–7.7)

3.7 (-9.0 to 16.4)

4.1 (0.6–7.6)

10.3 (-0.7 to 21.4)

16.7 (-6.7 to 40.2)

Mean BAC calculated assuming an

equal number of participants were

randomized to each group

Mean BAC calculated assuming an

equal number of participants were

randomized to each group

Confidence intervals calculated based

on P-value. Mean BAC calculated

assuming an equal number of

participants were randomized to

each group

Confidence intervals calculated based

on P-value. Mean BAC calculated

assuming an equal number of

participants were randomized to

each group

Mean difference calculated from means

of alcohol and placebo groups

assuming equal variance of means

Mean difference calculated from means

of alcohol and placebo groups

assuming equal variance of means

Linear regression compares alcohol

condition versus placebo and control

2.2 (0.6–3.8)

9.7 (-10.2 to 29.6)

Confidence intervals calculated based

on P-value

Excluded from meta-analysis due to

insufficient statistical information

Comments

2.1 (0.0–4.2)

5.7 (0.2–11.1)

Not significant

but unstated

7.7 (0.0–15.4)

Mean increase (as a % of

the scale) per 0.1 mg/ml

increase in BAC

Table 1 Summary of alcohol risk intentions studies that analyzed the relationship between BAC and likelihood of not using a condom through a randomized controlled trial.

Alcohol and intention for unprotected sex

55

Addiction, 107, 51–59

56

Jürgen Rehm et al.

%

Study

Linear

ID

Regression Beta (95% CI) Weight

Abbey et al. (2005)

0.08 (0.00, 0.15)

5.67

Davis et al. (2007)

0.06 (0.00, 0.11)

8.66

George et al. (2009)

0.02 (-0.00, 0.04)

16.49

George et al. (2009)

0.02 (0.01, 0.04)

17.88

Kruse et al. (2005)

0.10 (-0.10, 0.30)

1.10

Kruse et al. (2005)

0.17 (-0.07, 0.40)

0.81

Maisto et al. (2004)

0.10 (-0.01, 0.21)

3.23

Norris et al. (2009)

0.04 (0.01, 0.08)

12.92

Stoner et al. (2007)

0.04 (-0.09, 0.16)

2.50

Ebel-Lam et al. (2009)

0.29 (0.17, 0.41)

2.90

Schacht et al. (2010)

0.05 (0.02, 0.08)

14.93

Cho et al. (2010)

0.04 (0.01, 0.08)

12.92

Overall (I-squared = 61.4%, P = 0.003)

0.05 (0.03, 0.07)

100.00

NOTE: Weights are from random effects analysis

-0.405

0

0.405

0.15

Standard error

0.1

0.05

0

Figure 2 Forest plot of the 12 studies used in the meta-analysis and the weighted point estimates. The size of the box around the point

estimate is representative of the weight of the estimate in calculating the aggregated point estimate; CI: confidence interval

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

Point estimate

to 0.10 mg/ml this results in an increased perceived

likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex by 0.29% compared to what they perceived it as being when they were

at a BAC of 0 mg/ml. Before we discuss the implications of

these findings, the potential weaknesses associated with

this analysis should be mentioned.

© 2011 The Authors, Addiction © 2011 Society for the Study of Addiction

0.2

0.3

Figure 3 Funnel plot of the 12 studies

used in the meta-analysis with pseudo

95% confidence intervals. An Egger

weighted regression line was plotted and

indicates a right skew in the data

Most importantly, this investigation does not focus on

actual condom use, but instead examines the intentions

to use condoms. By focusing on intentions, rather than

behavior, it leaves open the possibility that in real-life situations the effect of alcohol on the incidence of new HIV

infections could be diminished by planned precautions

Addiction, 107, 51–59

Alcohol and intention for unprotected sex

(e.g. asking a friend to watch out for oneself). The combination of planned precautions with social influence and

structured behavioral interventions may be an effective

multi-level intervention strategy for preventing new HIV

infections, as the magnitude of the relationship between

alcohol consumption and the intention to have unprotected sex may be dependent on other factors [29].

However, given the high experimental realism of most

studies [30], as well as the reports on actual behaviors in

situations which could lead to unsafe sex [31], this possibility may be true in some instances but probably does not

pertain to the typical cases. It is likely that the underlying

cognitive processes that are undertaken are similar in

experimental settings as in real-world alcohol-related settings, suggesting that even in these ‘artificial’ conditions

under which intentions are being measured, alcohol may

impact cognitive capacity [7], in turn altering the ‘in-themoment’ risky behavioral intentions that may result. This

line of reasoning is supported further through investigations on generalized executive functioning and HIV risk

behavior, which have demonstrated significant associations between diminished planning and problem-solving

capabilities and risky behaviors, such as sharing injection

equipment for illicit drugs [e.g. 32,33]. Risk intentions

may thus serve as a valid surrogate of condom-related

behaviors that occur in real-world sexual encounters

[17–19].

Secondly, the reasoning that alcohol use is an independent risk factor for HIV incidence further assumes

that unsafe sex is indeed linked to HIV. The overwhelming research evidence supports this assumption (see [34]

for an overview). Additionally, as unsafe sex is also

linked to various other STIs [2], alcohol consumption

probably plays a role in the acquisition of these infections as well.

Because alcohol consistently had an effect on intentions in experimentally controlled settings, the argument

that personality factors explain fully the association

between alcohol consumption and unsafe sex, or the

association between alcohol consumption and HIV incidence, can be ruled out (e.g. [35]). This does not preclude,

however, that such factors may codetermine the magnitude of these relationships or the effects of the factors

associated with the context of alcohol consumption. For

instance, being in a bar-like atmosphere where there may

be novel sex partners may increase the probability of

engaging in unsafe sex.

The BAC in this study was never greater than

0.10 mg/ml and, thus, the results are limited to BAC

levels between 0.00 and 0.10 mg/ml. Capacity and functioning have been observed to decrease further where

BAC is above 0.10 mg/ml [7,36], and the effect of BAC

above 0.10 mg/ml on intentions and behavior may not

be linear.

© 2011 The Authors, Addiction © 2011 Society for the Study of Addiction

57

The studies included in the analysis are all from North

America, with all samples comprised of young men and

women, either from a university setting or a community

setting. Thus, the magnitude of the association may be

different in other age groups or populations.

Additionally, our study was limited by the exclusion of

studies that did not provide sufficient statistical information on the association between alcohol consumption and

the intent to engage in unprotected sex. Typically, studies

with non-significant results do not give a P-value, variance and/or SE for the association of interest which

typically causes them to be excluded from meta-analyses.

Given that these estimates are not published, the process

of adjusting our overall point estimate for publication

bias takes the exclusion of these studies into account.

Overall, in addition to the literature on the association

of alcohol use and HIV/STI [1,3,4] [2], we found evidence

on potential pathways explaining this association. Thus,

alcohol impacted on intentions about unsafe sex with a

clear dose–response relationship. This may, in large part,

be explained by its effect on cognitive functioning.

As alcohol affects detrimentally both the innate and

acquired immune system [37,38], many indications

point towards an important role of alcohol in the incidence of HIV and other STIs. Given the high prevalence of

alcohol consumption around the world [39,40], these

findings have potential public health implications. In this

context, both for scientific and public health reasons,

studies varying alcohol consumption experimentally

using proven effective interventions in at risk groups with

later measurement of incidence of HIV and STI would be

advisable [41,42].

Declaration of interests

Financial support for this study was provided to the

first author listed above by the National Institute for

Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) with contract

no. HHSN267200700041C to conduct the study entitled

‘Alcohol- and Drug-attributable Burden of Disease and

Injury in the US’. In addition, the first and last author

received a salary and infrastructure support from the

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The

authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

1. Baliunas D., Rehm J., Irving H., Shuper P. Alcohol consumption and risk of incident human immunodeficiency virus

infection: a meta-analysis. Int J Public Health 2010; 55:

159–66.

2. Cook R. L., Clark D. B. Is there an association between

alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases?

A systematic review. Sex Transm Dis 2005; 32: 156–64.

3. Fisher J. C., Bang H., Kapiga S. H. The association between

HIV infection and alcohol use: a systematic review and

Addiction, 107, 51–59

58

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

Jürgen Rehm et al.

meta-analysis of African studies. Sex Transm Dis 2007; 34:

856–63.

Kalichman S. C., Simbayi L. C., Kaufman M., Cain D., Jooste

S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in subSaharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings.

Prev Sci 2007; 8: 141–51.

Dingle G. A., Oei T. P. Is alcohol a cofactor of HIV and AIDS?

Evidence from immunological and behavioral studies.

Psychol Bull 1997; 122: 56–71.

O’Leary A., Hatzenbuehler M. Encyclopedia of drugs,

alcohol and addictive behavior. In: Carson-Dewitt R., editor.

Alcohol and AIDS. New York: Macmillan; 2009, p. 104–11.

Steele C., Josephs R. Alcohol myopia: its prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol 1990; 45: 921–33.

Shuper P. A., Neuman M., Kanteres F., Baliunas D., Joharchi

N., Rehm J. Causal considerations on alcohol and HIV/

AIDS—a systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol 2010; 45: 159–

66.

Halpern-Felsher B. L., Millstein S. G., Ellen J. M. Relationship

of alcohol use and risky sexual behavior: a review and

analysis of findings. J Adolesc Health 1996; 19: 331–6.

Leigh B. C., Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior

for exposure to HIV. Issues in methodology, interpretation,

and prevention. Am Psychol 1993; 48: 1035–45.

Shuper P. A., Joharchi N., Irving H., Rehm J. Alcohol as a

correlate of unprotected sexual behavior among people

living with HIV/AIDS: review and meta-analysis. AIDS

Behav 2009; 13: 1021–36.

Weinhardt L., Carey M. Does alcohol lead to sexual risk

behavior? Findings from event-level research. Annu Rev Sex

Res 2000; 11: 125–57.

Woolf S. E., Maisto S. A. Alcohol use and risk of HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2009;

13: 757–82.

Hendershot C. S., George W. H. Alcohol and sexuality

research in the AIDS era: trends in publication activity,

target populations and research design. AIDS Behav 2007;

11: 217–26.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

2005. National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and

Alcoholism—Recommended Council Guidelines on Ethyl

Alcohol Administration in Human Experimentation.

Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse

and Alcoholism. Available at: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/

Resources/ResearchResources/job22.htm (accessed 1

August 2010; archived by Webcite at http://www.

webcitation.org/61tJyRA6F).

World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for

Cancer Research (AICR). Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity,

and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: AICR; 2007.

Sheeran P., Abraham C., Orbell S. Psychosocial correlates of

heterosexual condom use: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull

1999; 125: 90–132.

Sheeran P., Orbell S. Do intentions predict condom use?

Meta-analysis and examination of six moderator variables.

Br J Soc Psychol 1998; 37: 231–50.

Albarracín D., Johnson B. T., Fishbein M., Muellerleile P. A.

Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as

models of condom use: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2001;

127: 142–61.

Liberati A., Altman D. G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gotzsche P.

C., Ioannidis J. P. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting

systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that

© 2011 The Authors, Addiction © 2011 Society for the Study of Addiction

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009; 6: 7.

Pagano M., Gauvreau K. Principles of Biostatistics. Pacific

Grove, USA: Brooks/Cole; 2000.

DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials.

Control Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–88.

Begg C. B., Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a

rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;

50: 1088–101.

Duval S. J., Tweedie R. L. Trim and fill: a simple funnel plotbased method of testing and adjusting for publication bias

in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000; 56: 276–84.

StataCorp. 2009. Statistical Software: Release 11.0. College

Station, TX: Stata Corporation.

Abbey A., Saenz C., Buck P. O., Parkhill M. R., Hayman L. W.

J. The effects of acute alcohol consumption, cognitive

reserve, partner risk, and gender on sexual decision making.

J Stud Alcohol 2006; 67: 113–21.

Ebel-Lam A. P., MacDonald T. K., Zanna M. P., Fong G. T.

An experimental investigation of the interactive effects of

alcohol and sexual arousal on intentions to have unprotected sex. Basic Appl Soc Psych 2009; 31: 226–33.

Egger M., Smith G. D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in metaanalysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;

315: 629–34.

Kalichman S. Social and structural HIV prevention in

alcohol serving establishments review of international

interventions across populations. Alcohol HIV/AIDS 2010;

33: 184–94.

Aronson E., Ellsworth P., Carlsmith J. M., Gonzales M.

Methods of Research in Social Psychology, 2nd edn. New York:

McGraw-Hill; 1990.

MacDonald T. K., Zanna M. P., Fong G. T. Why common

sense goes out the window: effects of alcohol on intentions to use condoms. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 1996; 22: 763–

75.

Severtson S. G., Mitchell M. M., Mancha B. E., Latimer W. W.

The association between planning abilities and sharing

injection drug use equipment among injection drug users in

Baltimore, MD. J Subst Use 2009; 14: 325–33.

Mitchell M. M., Severtson S. G., Latimer W. W. Interaction of

cognitive performance and knowing someone who has died

from AIDS on HIV risk behaviors. AIDS Educ Prev 2007; 19:

289–97.

Slaymaker E., Walker N., Zaba B., Collumbien M. Unsafe sex.

In: Ezzati M., Lopez A. D., Rodgers A., Murray C. J. L., editors.

Comparative Quantification of Health Risks. Global and

Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major

Risk Factors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004,

p. 1177–254.

Pearl J. Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Giancola P. R. Executive functioning: a conceptual framework for alcohol-related aggression. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 8: 576–97.

Friedman H., Newton C., Klein T. W. Microbial infections,

immunomodulation, and drugs of abuse. Clin Microbiol Rev

2003; 16: 209–19.

Friedman H., Pros S., Klein T. W. Addictive drugs and their

relationships with infectious diseases. FEMS 2006; 47:

330–42.

World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol

and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011.

Addiction, 107, 51–59

Alcohol and intention for unprotected sex

40. Shield K., Rehm M., Patra J., Rehm J. Global and country

specific adult per capita consumption of alcohol, 2008.

Sucht 2011; 57: 99–117.

41. Kalichman S. C., Simbayi L. C., Vermaak R., Cain D., Jooste

S., Peltzer K. HIV/AIDS risk reduction counseling for

alcohol using sexually transmitted infections clinic patients

in Cape Town South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr

2007; 44: 594–600.

42. Kalichman S. C., Simbayi L. C., Vermaak R., Cain D., Smith

G., Mthebu J. et al. Randomized trial of a community-based

alcohol-related HIV risk-reduction intervention for men and

women in Cape Town South Africa. Ann Behav Med 2008;

36: 270–9.

43. Abbey A., Saenz C., Buck P. O. The cumulative effects

of acute alcohol consumption, individual differences and

situational perceptions on sexual decision making. J Stud

Alcohol 2005; 66: 82–90.

44. Cho Y. H., Span S. A. The effect of alcohol on sexual risktaking among young men and women. Addict Behav 2010;

35: 779–85.

45. Davis K. C., Hendershot C. S., George W. H., Norris J.,

Heiman J. R. Alcohol’s effects on sexual decision making: an

integration of alcohol myopia and individual differences.

J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2007; 68: 843–51.

46. George W. H., Davis K. C., Norris J., Heiman J. R., Stoner

S. A., Schacht R. L. et al. Indirect effects of acute alcohol

intoxication on sexual risk-taking: the roles of subjective

and physiological sexual arousal. Arch Sex Behav 2009; 38:

498–513.

© 2011 The Authors, Addiction © 2011 Society for the Study of Addiction

59

47. Kruse M. I., Fromme K. Influence of physical attractiveness and alcohol on men’s perceptions of potential sexual

partners and sexual behavior intentions. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2005; 13: 146–56.

48. Agocha V. B., Cooper M. L. Risk perceptions and safer-sex

intentions: does a partner’s physical attractiveness undermine the use of risk-relevant information? Pers Soc Psychol

Bull 1999; 25: 746–59.

49. Maisto S. A., Carey M. P., Carey M. P., Carey K. B., Gordon C.

M., Schum J. L. et al. The relationship between alcohol and

individual differences variables on attitudes and behavioral

skills relevant to sexual health among heterosexual young

adult men. Arch Sex Behav 2004; 33: 571–84.

50. Helweg-Larsen M., Collins B. E. The UCLA Multidimensional

Condom Attitudes Scale: documenting the complex determinants of condom use in college students. Health Psychol

1994; 13: 224–37.

51. Norris J., Stoner S. A., Hessler D. M., Zawacki T. M., George

W. H., Morrison D. M. et al. Cognitive mediation of alcohol’s

effects on women’s in-the-moment sexual decision making.

Health Psychol 2009; 28: 20–8.

52. Stoner S. A., George W. H., Peters L. M., Norris J. Liquid

courage: alcohol fosters risky sexual decision-making in

individuals with sexual fears. AIDS Behav 2007; 11: 227–

37.

53. Schacht R. L., George W. H., Davis K. C., Heiman J. R., Norris

J., Stoner S. A. et al. Sexual abuse history, alcohol intoxication, and women’s sexual risk behavior. Arch Sex Behav

2010; 39: 898–906.

Addiction, 107, 51–59