The Model Wisconsin Exterior Lighting Code

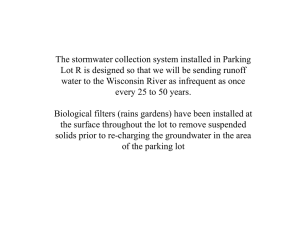

advertisement