The Senior Patient Navigator Program

advertisement

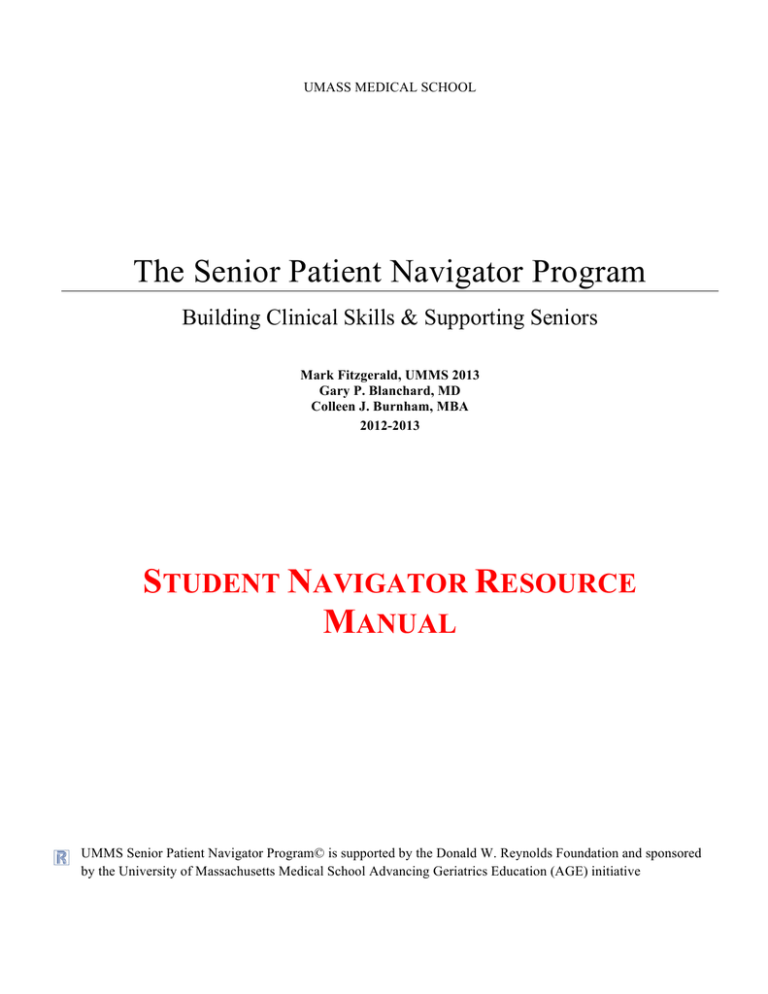

UMASS MEDICAL SCHOOL The Senior Patient Navigator Program Building Clinical Skills & Supporting Seniors Mark Fitzgerald, UMMS 2013 Gary P. Blanchard, MD Colleen J. Burnham, MBA 2012-2013 STUDENT NAVIGATOR RESOURCE MANUAL UMMS Senior Patient Navigator Program© is supported by the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation and sponsored by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Advancing Geriatrics Education (AGE) initiative Table of Contents PROGRAM HISTORY/BACKGROUND/RATIONALE 4 PROGRAM FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATION 6 TRAINING TO BECOME A STUDENT NAVIGATOR 7 TIMELINE OF A NAVIGATOR SESSION 8 HELPFUL TIPS FOR SUCCESSFUL NAVIGATION FROM EXPERT NAVIGATORS 10 OVERALL TIMELINE FOR STUDENT NAVIGATOR TRAINING 11 NOTE-TAKING TEMPLATE 12 NOTE-TAKING TEMPLATE SAMPLE 14 MODULE I: COMMUNICATING WITH OLDER ADULTS 16 Program Objectives 16 Medical, Nursing, Pharmacy, and Interprofessional Geriatric Competencies 17 Module I: Important Concepts 18 Module I: Clinical Pearls of Communication 19 Module I: Guiding Questions 21 Module I: Reading and Reference List 22 MODULE II: GERIATRIC PRESCRIBING 23 Program Objectives 23 Medical, Nursing, Pharmacy, and Interprofessional Geriatric Competencies 24 Module II: Important Concepts 25 Module II: Guiding Questions 26 Module II: Reading and Reference List 27 MODULE III: GERIATRIC SPECIALTY-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS 28 Program Objectives 28 Medical, Nursing, Pharmacy, and Interprofessional Geriatric Competencies 29 Module III: Cardiology Clinical Pearls 31 Module III: Orthopedic Clinical Pearls 33 A Brief Introduction to Third Year & The Hospitalized Patient 35 Module III: Guiding Questions 36 Module III: Reading and Reference List 37 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e |2 MODULE IV: END-OF-LIFE CARE AND CONSIDERATIONS 38 Program Objectives 38 Medical, Nursing, Pharmacy, and Interprofessional Geriatric Competencies 39 Module IV: Guiding Questions 40 Module IV: “On Breaking Bad News and Speaking of Death” 41 Module IV: Reading and Reference List 45 RESOURCES OVERVIEW 46 Program Objectives Addressed in Resources Overview 46 INDEX 47 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e |3 P ROGRAM H ISTORY The Senior Patient Navigator Program is an original University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS) geriatric curriculum targeting first-year and second-year medical students, graduate nursing students, pharmacy students. The brainchild of Bonnie Vallie (Class of 2011), the program’s goal was to afford medical students an early clinical exposure to geriatricians and other specialists who see older patients in the ambulatory setting. Bonnie Vallie formulated the idea of the Senior Patient Navigator Program during the 2008-2009 academic year. The pilot of the program took place the following academic year as an extra-curricular student activity for the School of Medicine implemented and facilitated by Romulo Celli (Class of 2012). Originally based out of the cardiology clinic on the School of Medicine’s University campus, older adult patients with upcoming cardiology appointments could call a phone line and request a preclinical medical student to accompany them into their appointments. The students would transcribe important notes during the visit and debrief with the patient after the appointment. The program was found to have mutual benefit for students and patients, and received positive feedback from students, physicians, patients, and caregivers. While successful, it was felt the program had untapped potential and was not entirely self-sustaining long term. Mark Fitzgerald (Class of 2013) reengineered the program from the ground up and a new iteration of the Navigator Program was rolled out during the 2010-2011 academic year. Rather than being clinic based, the program now centered on pairing each participating student with an older adult patient under the care of a geriatrician. The student would attend the patient’s appointments across multiple sub-specialties in addition to their primary care appointments, providing the student with a longitudinal clinical experience. Students were supplied with a manual addressing topics pertinent to the navigation and care of older adults while small group meetings facilitated by geriatrician faculty were held throughout the year to discuss the learning modules from the manual. The program also expanded, serving as a pilot for nursing student participation and interprofessional learning. The program was awarded status as an optional enrichment elective (OEE) for the school of medicine during the academic year, with fifteen medical and nursing students participated as the first group of navigators to complete the newly designed elective. The program continued to develop and grow in popularity the following year. Additional topics for discussion were added to the student manual, as the program was refined to provide the optimum learning experience. Effort is being invested to continue fostering the growth of the program. This is illustrated by the further expansion of the program to include pharmacy students, as well as nurse practitioner and pharmacy mentors in the 2012-2013 academic year. The program is now actively pursuing the goals of building clinical skills, providing longitudinal experiences, and encouraging interprofessional learning for students, while providing valuable support of older adults and their caregivers. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e |4 B ACKGROUND /R ATIONALE The Navigator works by pairing a nursing, pharmacy, MS1, or MS2 student with an older patient, whom they “navigate” through their various outpatient medical encounters during an academic year to help the patient more fully understand their health problems and treatments. Through this immersive experience, students will be able to: Consider the complexity of multiple medical morbidities, polypharmacy, and involvement of family members when communicating with older persons in the ambulatory setting, and later apply the experiences during their clinical years. Receive exposure to basic skills of reconciling a patient’s medications, including prescribed, herbal, and over-the-counter medications. Recognize health literacy issues affecting older patients and to develop skills to surmount communication barriers. Consider how integrative geriatric care is managed across specialties- particularly in oncology- thanks to an interprofessional partnership for navigating patients Weigh standard recommendations for health screenings and treatments with the age, functional status, and the goals of care for their older patients. Reflect upon the psychological, social, and spiritual needs of their patients with advanced illness and patient family members. Actively participate in interprofessional communication, problem-solving, and education Upon enrollment, new Student Navigators (SNs) receive the Student Navigator Resource Manual that includes literature on effective communication with older persons, geriatric prescribing, geriatric specialty-specific considerations, and end-of-life care. During the academic year, geriatrician, nurse practitioner, and pharmacist faculty advisors facilitate four small group sessions (offered during fall and spring semesters) with participating SNs to teach the seven goals mentioned above. Geriatricians and nurse practitioners involved in the Navigator Program pair SNs with patients in their practice, who then longitudinally follow those patients to sub-specialist appointments. At appointments, the SN’s responsibilities include accompanying the older patient into the examination room and taking notes on a standardized template to document the visit. Immediately afterward, the SN summarizes the information with the patient (and caregiver) and provides a copy of the encounter form. The student navigator works with the patient to arrange follow-up appointments with sub-specialists after his or her first office visit with the patient. Students learn to contrast the different communication styles as well as challenges employed by primary providers and specialists. Ultimately, we hope the Navigator Program will influence the communication style and outlook of health profession students toward older patients by offering an early clinical exposure and small group teaching sessions with academic geriatricians, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists. Sincerely, Dr. Gary Blanchard, Dr. Sarah McGee, Dr. Erika Oleson Geriatrician Faculty Advisors to the Navigator Program UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e |5 Program Faculty and Administration Gary Blanchard, MD Geriatrician Faculty Advisor 508.856.4250 Gary.Blanchard@umassmed.edu Sarah McGee, MD, MPH Geriatrician Faculty Advisor 508.334.6251 Sarah.McGee@umassmed.edu Erika Oleson, DO, MS Geriatrician Faculty Advisor 508.334.6251 Erika.Oleson@umassmemorial.org Mary Ellen Keough, MPH Reynolds/AGE Project Director Director of Educational Programs Meyers Primary Care Institute 508.791.7392 MaryEllen.Keough@umassmed.edu Megan Janes Geriatrics Interest Group Co-leader UMMS Class of 2015 Megan.Janes@umassmed.edu Benjamin Vaughan Geriatrics Interest Group Co-leader UMMS Class of 2015 Colleen Burnham, MBA AGE Curriculum Resources Office of Educational Affairs Colleen.Burnham@umassmed.edu Mark Fitzgerald Navigator Consigliore SOM, Class of 2013 Mark.Fitzgerald@umassmed.edu Benjamin.Vaughan@umassmed.edu UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e |6 T RAINING TO B ECOME A S TUDENT N AVIGATOR Navigator training is presented in two parts, which are most effective when presented sequentially. Part I The Student Navigator Leaders provide the Student Navigator Resource Manual to students upon enrollment in the program. Materials include orientation information, training instructions, blank templates for note-taking and assessment, relevant articles presented in learning modules, and useful resources for patients and Student Navigators (SNs). The prospective SN is asked to read the training/orientation section upon receipt of the manual. The prospective SN is not expected or required to read the entire manual all at once. Throughout the semester, SNs attend four small group meetings hosted by a faculty advisor. Each small group meeting addresses one of the four learning modules. Prospective SNs are encouraged to read the corresponding learning module before the meeting in order to be prepared to discuss the topic. Each module begins with a summary of the included materials, a list of important concepts; ending with guiding questions for the prospective SN to consider. For each learning module, the prospective SN is encouraged to think critically about how the content of each section is clinically relevant. Additionally, prospective SNs are encouraged to click on the following link and become oriented with the information on the UMMS Advancing Geriatric Education (AGE) website: http://umassmed.edu/AGE/index.aspx. A presentation by Dr. Gerry Gleich is accessible on the AGE website under the ‘Geriatrics Interclerkship 2010’ tab of ‘UMMS AGE Curriculum Development’. This presentation gives an overview of many of the following learning modules; it is accessible via the following link: http://onlinetraining.umassmed.edu/p49355707/ Online PowerPoint files included in this manual are timed for 3-5 seconds per slide and do not have audio. Slideshows are intended as exposure to the material rather than mastery of all the information in them. The SN can use the pause button on detailed automated presentation slides. Part II Two videos of actual Navigator sessions are in development. The Prospective Navigator will view both videos and take notes on a blank template as if they were actually navigating the patient. Immediately following the appointment, the SN has the opportunity to compare his or her notes with those taken by the SN in the video. Look for similarities and differences between the model notes and your own, including details that may be superfluous or missing. The prospective SN should also note the flow and content of the Student Navigator meeting with the patient prior to the appointment and afterward as well. The videos are intended as general models to highlight the important particulars, but each SN will have his or her own personality and method of interacting with the patients they navigate. The following pages show a completed demonstration template. Keep in mind the content of the notes taken will likely vary from session to session. Any questions about the goals and or logistics of patient navigation may be directed to either the current GIG coleaders (Ben Vaughan, Meagan Jane), or the geriatrician faculty advisors to the Navigator Program (Dr. Gary Blanchard, Dr. Sarah McGee, Dr. Erika Oleson). UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e |7 T IMELINE OF A N AVIGATOR S ESSION 15 Minutes Prior to Appointment Student Navigator (SN) and elder meet outside of physician’s office. If patient and SN are not previously acquainted, SN will introduce him/herself. “Hi Mr/s. ______. My name is _____ _________ and I am a nursing/pharmacy/medical student at UMMS/UMass GSN/MCPHS. I will accompany you in your appointment and take notes based on what the provider says (about your health, medications, and any instructions s/he wants you to follow).” If patient is new to program, the SN explains the purpose and goals of the program, as well as the services the SN provides. “The Navigator Program is meant to help health profession students learn by working with patients and health care providers. The hope is the program also helps the patient; you do not have to remember everything the provider says because I will take notes and give them to you.” The SN asks if there are any questions or concerns the patient has. “Are there any questions you have for the doctor that you would like me to remind you about during the appointment?” During the Appointment Accompany the patient into the examination room. Observe the patient-clinician interaction and the physical exam, taking structured notes using the specially designed template. At the end of the appointment, ask the provider to look over the notes taken on the template and initial them if the physician desires. Following the Appointment After the visit, the SN and patient “debrief” in a private area of the office to review. Use this time to clarify key points of the visit, their patient’s vital signs, weight, lab/test results, and any changes to their medication regimen. Ex. “Dr. _____ said your blood pressure was good, and your cholesterol was great.” Ex. “Did you have questions about anything else that the doctor said?” Use this time to explain any complicated medical terms that may have been unclear. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e |8 ***It is necessary to emphasize that Student Navigators should translate medical language used during the appointment; Student Navigators should not take notes or give advice based on interpretation. It is also okay to not know an answer to a question asked by the patient. The SN provides the patient and or family member with a copy of the Navigator notes from the visit, along with the medication list if feasible. Work with the patient to schedule any follow-up visits at mutually suitable times for you both. It may be helpful to bring an academic calendar to check for any conflicts while coordinating the follow-up visit. Keep in mind that as an elective, class time should take precedence over the Navigator Program and you may not always be able to plan a follow-up appointment that fits everyone’s schedules. Choosing to skip class time for navigation commitments should be done at your discretion and judgment. Each SN will complete an evaluation of their clinical encounters once a semester using either BLS Vista (Blackboard) or E-Value. Evaluation data is pivotal for improving the program each year, and allow the faculty to be responsive to SN feedback. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e |9 H ELPFUL T IPS FOR S UCCESSFUL N AVIGATION FROM E XPERT N AVIGATORS Bonnie Vallie Romulo Celli Class of 2011 Class of 2012 Visionaries and Founders of the Navigator Program A caregiver may accompany elderly patients to their appointments; make sure you are attentive and responsive to both patient and caregiver. Elderly patients will have many different levels of cognitive functioning. Try to summarize at a level appropriate for their understanding. If you are unsure about the accuracy of a note you recorded (especially any change in medication), double check with the doctor. Write neatly and large enough for your notes to be legible even if the patient has some vision loss. The notes you take serve as a valuable reference for the patient. If you are unsure of the answer to a question, it is always best to say, “I don’t know”. Bring extra note-taking templates to appointments. It may be helpful to quickly scribble notes down on one set during the appointment and then copy them over neatly afterward. As you get to know the patient over multiple visits, you may find yourself in a position to advocate for the patient in specific situations. Always be polite and respectful toward the health care provider, and use common sense to advocate appropriately on behalf of the patient and/or caregiver UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 10 O VERALL T IMELINE FOR S TUDENT N AVIGATOR T RAINING Note that each blocked event only runs ~1-2 hours. Time ranges are blocked for probable time-periods during which that event may occur. Date Event (Small Group/ Module) August (Early) Objective: Student Navigator Recruitment Location: Activities Fair Objective: Student Navigator Orientation Location: TBA PSN Preparation: Read Training section of Manual Objective: Student Navigator Small Group Meeting #1 Location: TBA PSN Preparation: Read Module I in Manual August (Late) September ~ October Event (Clinical Experience) Estimated Time Commitment for Prospective Student Navigator (PSN) n/a Orientation Meeting: ~ 1 hour Objective: StudentPatient Navigator Session 1 Prep for Small Group: ~1 hour Small Group Meeting: ~2 hours Supervised Navigator Session: ~ 1 hour November ~ December Objective: Student Navigator Small Group Meeting #2 Location: TBA PSN Preparation: Read Module II in Manual Objective: StudentPatient Navigator Session 2 Prep for Small Group: ~1 hour Small Group Meeting: ~2 hours Supervised Navigator Session: ~ 1 hour January ~ February Objective: Student Navigator Small Group Meeting #3 Location: TBA PSN Preparation: Read Module III in Manual Objective: StudentPatient Navigator Session 3 Prep for Small Group: ~1 hour Small Group Meeting: ~2 hours Supervised Navigator Session: ~ 1 hour March ~ April Objective: Student Navigator Small Group Meeting #4 Location: TBA PSN Preparation: Read Module IV in Manual Objective: Additional Navigator Sessions Prep for Small Group: ~1 hour Small Group Meeting: ~2 hours Additional Supervised Navigator Session(s): ~ 1 hour per session Total First Year Commitment: ~ 16 - 20 hours UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 11 Note-Taking Template UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 12 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 13 N OTE -T AKING T EMPLATE S AMPLE UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 14 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 15 M ODULE I: C OMMUNICATING WITH O LDER A DULTS Summary This module focuses on communication between health care providers, patients, and caregivers. It explores effective ways to communicate, as well as barriers that may arise in clinical situations. Module I has three parts: one online video, a narrated PowerPoint presentation, and a sections of clinical pearls. The video in Part 1 is presented by the American Medical Association (AMA) and discusses health literacy and can be accessed via the link below. The PowerPoint covers tips for improving doctor/caregiver communication, studies examining health literacy in older adults, and how health literacy is tested. It can be accessed via Blackboard Vista. The clinical pearls section is included in this binder; it discusses common challenges and solutions in communicating with older adults. Part 1 Health Literacy and Patient Safety: Help Patients Understand American Medical Association http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGtTZ_vxjyA Part 2 Communication & Health Literacy in Older Adults Fitzgerald Part 3 Clinical Pearls of Managing Communication Challenges Blanchard PROGRAM OBJECTIVES ADDRESSED Consider the complexity of involvement of family members and or caregivers, and possible cognitive impairment when communicating with older persons in the ambulatory clinical setting. Develop communication skills for effectively relating to older patients and apply them during their clinical years. Recognize health literacy issues affecting older patients. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 16 MODULE I: COMMUNICATING WITH OLDER ADULTS: MEDICAL, NURSING, PHARMACY, AND INTERPROFESSIONAL COMPETENCIES AACN & JOHN A. HARTFORD FOUNDATION ADULT-GERONTOLOGY PRIMARY CARE NURSE PRACTITIONER COMPETENCIES Practitioner- Patient Relationship: Provides support through effective communication and therapeutic relationships with individuals, families, and caregivers facing complex physical and/or psychosocial challenges. Practitioner- Patient Relationship: Uses culturally appropriate communication skills adapted to the individual’s cognitive, developmental, physical, mental and behavioral health status. Teaching-Coaching Function: Adapts teaching-learning approaches based on physiological and psychological changes, age, developmental stage, readiness to learn, health literacy, the environment, and resources. Professional Role: Directs and collaborates with both formal and informal caregivers and professional staff to achieve optimal care outcomes ASCP GERIATRIC PHARMACY CURRICULUM GUIDE COMPETENCIES Communication: Demonstrate skill in communicating drug and adherence information (verbal and written) to senior patients, their caregivers and the interprofessional care team. Communication: Demonstrate proficiency to interview and counsel seniors with varying degrees of cognitive and communication abilities. Communication: Recognize barriers to effective communication (e.g., cognitive, sensory, cultural, and language). Education: Utilize educational material appropriate to the specific patient/caregiver. CORE COMPETENCIES FOR INTERPROFESSIONAL COLLABORATIVE PRACTICE VE5. Work in cooperation with those who receive care, those who provide care, and others who contribute to or support the delivery of prevention and health services. RR1. Communicate one’s roles and responsibilities clearly to patients, families, and other professionals. CC1. Choose effective communication tools and techniques, including information systems and communication technologies, to facilitate discussions and interactions that enhance team function. CC2. Organize and communicate information with patients, families, and healthcare team members in a form that is understandable, avoiding discipline-specific terminology when possible. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 17 MODULE I: COMMUNICATING WITH OLDER ADULTS: IMPORTANT CONCEPTS Low health literacy is an extremely prevalent problem, with 60% of adults age 65+ at a basic or below basic health literacy level. The causes of low or declining health literacy are diverse, but they can usually be organized by identifying with of the three “In’s” (intake, interpret, and interact) the cause is interfering with (ex. Loss of vision limits a patient’s ‘intake’ ability, while dementia may limit the ability to interpret). Hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia may all lead to cerebrovascular disease and stroke, which can affect reading ability. Moreover, several studies have shown that individuals who have hypertension are more likely to have a decline in cognitive function, even in the absence of a stroke. The Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA) has shown health literacy to be closely inversely correlated with age. Figure 1. Mean scores on the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults for five age groups, stratified according to years of school completed: >12 yr (black circle; n = 898), 12 yr (white circle; n = 998), 9–11 yr (black triangle; n = 526), and 0–8 yr (white triangle; n = 352). The bars indicate standard errors (Baker, Gazmararian, Sudano, Patterson, 2000). A patient with low health literacy may find most patient education materials that are distributed in physicians’ offices to be too complex, written at too high a level, or not organized from the patient perspective. Having a companion or caregiver with the patient can create a specific type of triadic dialogue that is uniquely common to geriatrics (some say it is like turning a pediatric triadic interview on its head). It is important to obtain information from both patient and caregiver without alienating or ignoring either party. A language barrier can occasionally be a hurdle in effective communication in elderly populations. Often surmounting this hurdle requires a set communication skills, including experience with a triadic interview and the ability to break down information so it can be translated. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 18 MODULE I: COMMUNICATING WITH OLDER ADULTS: CLINICAL PEARLS OF MANAGING COMMUNICATION CHALLENGES MEDIUMS OF COMMUNICATION Non-verbal Communication Personal Space: be aware most people prefer 1 1/2 to 3 feet of space around them. Assess their mood and attitude. Utilize congruent facial expressions. Use gestures to clarify your point. Paraverbal Communication Be aware of how your message is perceived. Attend to tone: respectful Assess volume: consider possible hearing impairment Attend to cadence: keep your rhythm slow and deliberate Verbal Communication Use simple, direct statements, enunciate words, avoid terms of endearment or infantilizing. Utilize Mr. or Mrs., Ms. until granted permission otherwise… Ask! Always acknowledge the patient directly, address the family member or caregiver afterward. Never ignore the patient. Power of Attorney is only an enforced power if the patient becomes incapacitated. Ask open-ended questions and avoid giving ‘fill in the blank’ responses (unless format is necessary because of cognitive deficiency). Do not skirt issues (depression, suicide, alcohol, finances, abuse). Allow plenty of time for responses. Empathic Listening An active process, provide undivided attention. Remember to restate, rephrase and clarify. Allow for silence. BARRIERS TO COMMUNICATION Hearing impaired Possible Solution: Stand directly in front of the person, make sure you have that individual’s attention and that you are close enough to the person before you begin speaking to reduce or eliminate background noise. Possible Solution: Use a portable amplifier system; speak slowly and distinctly. Visually impaired Possible Solution: Explain what you are doing as you are doing it. Ask how you may help: increasing the light, reading the document, and/or describing where things are. Possible Solution: Write instructions in large font with a dark marker. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 19 Dementia Introduce yourself each time. Use short simple sentences or questions and give plenty of time for the person to respond. Maintain a calm demeanor; dementia patients may mirror emotion. Redirect and distract out of stressful situations. Dementia: Understanding Behaviors Dementia can affect areas in the brain that control emotion and behavior. The person’s ability for insight and judgment may be impaired. Confusion limits one’s ability to understand their surrounding and or to express themselves conventionally. Dementia: Further Tips for Communication Speak slowly using simple sentences. Ask simple questions that require a choice or a yes/no answer. Use concrete terms and familiar words. Always introduce yourself, don’t expect the person to know your name no matter how long you have known them. Prompt the person with information instead of testing their knowledge. Offer choices when possible (e.g., Do you live at home or with family?). Use gestures and visual cues to get your message across. Speak in a warm, easy-going, pleasant manner. Use humor and cheerfulness when possible. If the person is hard of hearing, speak into their ear instead of yelling louder. Consider the use of hearing aids or a headset amplifier. Assist the patient in note-taking, marking things on a calendar. Ask family to assist by providing reminders, and to consider use of a medical alert system for safety and medication prompting. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 20 MODULE I: COMMUNICATING WITH OLDER ADULTS: GUIDING QUESTIONS Why is it difficult to communicate with older adults? Compared to other students at your level in training, do you feel you are below average, average, or above average in your ability to communicate with older adults? What are the potential benefits and possible pitfalls to having a caregiver or companion accompanying the patient to an appointment? Why is health literacy especially a concern in older adult populations? What other populations might be at risk for low health literacy? What are the three components of health literacy (mentioned in the video)? What problems can arise if a patient has low health literacy? UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 21 MODULE I: COMMUNICATING WITH OLDER ADULTS: READING AND REFERENCE LIST Baker D, Gazmararian J., Sudano J, Patterson M. The association between age and health literacy among elderly persons. Journal of Gerontology: SOCIAL SCIENCES 2000; 55B(6): S368-S374. Health literacy in clinical practice. Retrieved http://cme.medscape.com/viewarticle/566053_5 June 18, 2012. National Family Caregivers Association. Improving doctor/caregiver communications. www.nfcacares.org. Parker R, Baker D, Williams M, Nurss J. The test of functional health literacy in adults: A new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. Jounal of General Internal Medicine; 10(10) October 1995: 537-541. S-TOHFLA Retrieved November 8, 2011: http://www.nmmra.org/resources/Physician/152_1485.pdf. Weiss BD. Assessing health literacy in clinical practice. Medscape 2007. http://sme.medscape.com/viewarticle/566053. Accessed August 25, 2012 [requires free registration to MedScape CME site to view] ADDITIONAL RESOURCES FOR FURTHER LEARNING American College of Physicians Health Literacy Resources http://foundation.acponline.org/hl/hlresources.htm American College of Physicians Ethics and Human Rights Committee: Family caregivers, patients and physicians: ethical guidance to optimize relationships. http://www.springerlink.cin.ioebyrk.asp?genre=article&id=doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1206-3. Strategies to Improve Communication Between Pharmacy Staff and Patients: A training Program for Pharmacy Staff http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/pharmlit/pharmtrain.htm TOFHLA Teaching Version. Available for purchase from Peppercorn Books http://www.peppercornbooks.com. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 22 M ODULE II: G ERIATRIC P RESCRIBING Summary This module focuses on the complexity of managing multiple medications in older adults with regard to proper dosing, prescribing cascades, and adverse drug reactions. Module I has four parts: two PowerPoint presentations for students to scroll through, a third narrated PowerPoint presentation, and a link to the AGS Beer Criteria Printable Pocket Card. The first two presentations are accessed online via the links provided; the slides do not have audio and are intended for exposure to the material rather than mastery of all the information contained on them. Students should progress through the PowerPoints at their own pace; for more detailed slides, it is possible to pause the presentation. Some of the important concepts are repeated among the presentations. The narrated PowerPoint presentation can be accessed via Blackboard Vista; it provides a review of important topics from the first two presentations, describes some clinical pearls for geriatric prescribing, and offers an introduction to anticoagulation in the older adult. Students are encouraged to print out the AGS Beer Criteria Printable Pocket Card for reference and discussion in regards to its usefulness and purpose. Part 1 Making Medication Use Safer in Older Adults http://onlinetraining.umassmed.edu/p35814819/ Part 2 Drug Therapy in the Elderly http://onlinetraining.umassmed.edu/drug_therapy/ Part 3 Geriatric Prescribing Parts I & II Tjia Gurwitz Fitzgerald Part 4 AGS Beers Criteria Printable Pocket Card American Geriatrics Society http://www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/beers/PrintableBeersPocketCard.pdf PROGRAM OBJECTIVES ADDRESSED Consider the complexity of multiple medical co-morbidities and polypharmacy when communicating with older persons in the ambulatory clinical setting. Increase awareness of medication reconciliation, including prescribed, herbal, and over-the-counter medications. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 23 MODULE II: GERIATRIC PRESCRIBING: MEDICAL, NURSING, PHARMACY, AND INTERPROFESSIONAL COMPETENCIES AAMC & JOHN A. HARTFORD FOUNDATION GERIATRIC COMPETENCIES FOR MEDICAL STUDENTS Medication Management: Explain impact of age-related changes on drug selection and dose based on knowledge of age-related changes in renal and hepatic function, body composition, and Central Nervous System sensitivity. Identify medications, including anticholinergic, psychoactive, anticoagulant, analgesic, hypoglycemic, and cardiovascular drugs that should be avoided or used with caution in older adults and explain the potential problems associated with each. Medication Management: Document a patient’s complete medication list, including prescribed, herbal and over-the-counter medications, and for each medication provide the dose, frequency, indication, benefit, side effects, and an assessment of adherence. AACN & JOHN A. HARTFORD FOUNDATION ADULT-GERONTOLOGY PRIMARY CARE NURSE PRACTITIONER COMPETENCIES Management of Patient Health/Illness: Conducts a pharmacologic assessment addressing polypharmacy; drug interactions and other adverse events; over-the-counter; complementary alternatives; and the ability to obtain, purchase, self administer, and store medications safely and correctly. Management of Patient Health/Illness: Prescribes medications with particular attention to high potential for adverse drug outcomes and polypharmacy in vulnerable populations, including women of childbearing age, adults with co-morbidities, and older adults. ASCP GERIATRIC PHARMACY CURRICULUM GUIDE COMPETENCIES Biology of Aging: Discuss the physiologic changes associated with aging and how they impact medication therapy. Biology of Aging: Apply the knowledge of aging physiology to the clinical use of medications. Communication: Demonstrate skill in communicating drug and adherence information (verbal and written) to senior patients, their caregivers and the interprofessional care team. Communication: Demonstrate proficiency to interview and counsel seniors with varying degrees of cognitive and communication abilities. Communication: Recognize barriers to effective communication (e.g., cognitive, sensory, cultural, and language). Pathophysiology: Recognize medication-induced disease. Geriatric Assessment: Obtain and interpret the medication history in relation to patient's current health status. Geriatric Assessment: Recognize the relationship between geriatric syndromes/diseases and medication-related problems. Education: Ensure understanding of medication use and its role in the overall treatment plan. CORE COMPETENCIES FOR INTERPROFESSIONAL COLLABORATIVE PRACTICE RR3: Engage diverse healthcare professionals who complement one’s own professional expertise, as well as associated resources, to develop strategies to meet specific patient care needs. TT3: Engage other health professionals- appropriate to the specific care situation- in shared patient-centered problem-solving UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 24 MODULE II: GERIATRIC PRESCRIBING: IMPORTANT CONCEPTS The amount of medication use in the elderly is much higher, compared to younger populations. 40% of people >65 years old use >5 medications, while 12% of the elderly population uses >10 medications. Nearly 1/3rd (1.9 million) of Adverse Drug Events are preventable. Of the most serious, life-threatening ADEs, over 40% are preventable. Body composition changes with age: muscle mass decreases while lipid storage increases. This can profoundly affect the half-life of lipid soluble drugs. Decrease in kidney function can also affect the half-life of medications as well. Older adults have slower metabolism, excretion of drug as well as increase sensitivity. The saying, “start low, go slow” is used to refer to medication dosing The types of medications most commonly involved in adverse drug events relate closely to those most frequently prescribed in the ambulatory setting, with cardiovascular drugs and antibiotics/anti-infectives are the most frequently used and implicated drug categories. Some of the common problems with Polypharmacy are more adverse drug reactions, decreased adherence to drug regimens, poor quality of life, high rate of ADEs and or side effects, and (unnecessary) drug expense. Factors contributing to polypharmacy are underreporting symptoms, use of multiple providers, use of others’ medications, limited time for discussion, limited knowledge of geriatric pharmacology (clinician), and low health literacy leading to poor understanding of purpose of medications (patient) Factors contributing to non-adherence are a high number of medications, expense of medications, complex or frequently-changing dosing schedule(s), adverse reactions, confusion about brand /trade name, difficult-toopen containers, rectal/vaginal/SQ (unpopular) modes of administration, and limited patient health literacy General Model of a ‘prescribing cascade’ UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 25 MODULE II: GERIATRIC PRESCRIBING: GUIDING QUESTIONS What have been your experiences regarding medication use in older adults? Do you have parents or grandparents on multiple medications? Do you know any family members who are been hospitalized because of an adverse drug event? What sort of medications does the patient you navigate take? What is Medication Reconciliation? What is the purpose of medication reconciliation and what are the essential steps in the process? Why are elderly patients at a high risk for ‘prescribing cascades’? What are 2-3 clinical examples of instances where prescribing cascades can develop? What are some effective ways to reduce the number and cost of medications for an elderly patient? What 4 factors of pharmacokinetics change with aging? What organ systems undergo normal age-related physiologic changes that influence how to prescribe medications for older adults? Discuss anticoagulation in older adults. What concerns, considerations, and challenges occur? UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 26 MODULE II: GERIATRIC PRESCRIBING: READING AND REFERENCE LIST American Geriatrics Society. AGS Beers Pocket Card. Accessed http://www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/beers/PrintableBeersPocketCard.pdf August 25, 2012. Gurwitz J. Drug Therapy in the Elderly. PowerPoint presentation at the Chief Resident Immersion Training. Accessed http://onlinetraining.umassmed.edu/drug_therapy/ August 25, 2012. Gurwitz J, Field T, Harrold L, Rothschild J, Debellis K, Seger A, Cadoret C, Fish L, Garber L, Kelleher M, Bates D. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA: March 5, 2003; 289(9): 1107-1096. Rochon P, Gurwitz J. Optimizing drug treatment for elderly people: the prescribing cascade. BMJ 1997; 315: 10961099 (25 October). Tjia J. Making medication use safer in older adults. PowerPoint presentation at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Accessed http://onlinetraining.umassmed.edu/p35814819/ August 25, 2012 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 27 M ODULE III: G ERIATRIC S PECIALTY -S PECIFIC E XPERIENCES & C ONSIDERATIONS Summary This module explores how integrative geriatric care for a medically complex patient is managed across specialties. This module is intended to supplement clinical experiences unique to each student navigator, so therefore it is not expected that you- the student navigator- read the entire module. Instead, read the introductory article “The Way We Age Now” by Atul Gawande and Part 8: The Hospitalized Patient. Additionally, select one or two sections from Parts 2 through 7 based on experiences in clinical navigation sessions. If a navigation session took place in a specialty not listed here, alternatively a student navigator may choose to look up information regarding geriatric considerations for that specialty. The small group session that accompanies this module will be mostly focused on student navigators sharing impressions of their specialty navigation sessions. Part 1: Introduction The Way We Age Now http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/04/30/070430fa_fact_gawande Gawande Part 2: Geriatric Psychiatry 3D Geriatrics: Dementia, Delirium, and Depression http://onlinetraining.umassmed.edu/p97121950/ The 3D’s Continued: Clinical Pearls Fitzgerald Part 3: Geriatric Cardiology Cardiology Clinical Pearls Heart Disease in Older Adults Blanchard Fitzgerald Part 4: Geriatric Orthopedics Orthopedic Clinical Pearls Considerations Treating Older Adults in Orthopedics Blanchard Fitzgerald Part 5: Geriatric Oncology The Older Adult with Cancer: Considerations and Pearls for Treatment Fitzgerald Part 6: Pain Management Clinical Pearls of Managing Persistent Pain in the Older Adult Fitzgerald Part 7: Rheumatologic Diseases Geriatric Rheumatology http://www.ouhsc.edu/geriatricmedicine/Education/GeriatricRheumatology/index.htm Part 8: The Hospitalized Patient What to do when your Patient is Hospitalized & A Brief Introduction to Third Year Gleich Nakasato Fitzgerald PROGRAM OBJECTIVES ADDRESSED Consider the complexity of multiple medical co-morbidities and possible cognitive impairment when communicating with older persons in the ambulatory clinical setting. Weigh standard recommendations for health screenings and treatments with the age, functional status, and the goals of care for older patients. Reflection upon the psychological, social, and spiritual needs of patients with advanced illness and their family members. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 28 MODULE III: GERIATRIC SPECIALTY-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS: MEDICAL, NURSING, PHARMACY, AND INTERPROFESSIONAL COMPETENCIES AAMC & JOHN A. HARTFORD FOUNDATION GERIATRIC COMPETENCIES FOR MEDICAL STUDENTS Cognitive and Behavioral Disorders: Define and distinguish among the clinical presentations of delirium, dementia, and depression Cognitive and Behavioral Disorders: Perform and interpret a cognitive assessment in older patients for whom there are concerns regarding memory or function. Health Care Planning and Promotion: Define and differentiate among types of code status, health care proxies, and advanced directives in the state where one is training. Health Care Planning and Promotion: Accurately identify clinical situations where life expectancy, functional status, patient preference or goals of care should override standard recommendations for screening tests in older adults. Health Care Planning and Promotion: Accurately identify clinical situations where life expectancy, functional status, patient preference or goals of care should override standard recommendations for treatment in older adults. Palliative Care: Assess and provide initial management of pain and key non-pain symptoms based on patient’s goals of care. Hospital Care for Elders: Identify potential hazards of hospitalization for all older adult patients (including immobility, delirium, medication side effects, malnutrition, pressure ulcers, procedures, peri and post operative periods, and hospital acquired infections) and identify potential prevention strategies. AACN & JOHN A. HARTFORD FOUNDATION ADULT-GERONTOLOGY PRIMARY CARE NURSE PRACTITIONER COMPETENCIES Management of Patient Health/Illness: Assesses individuals with complex health issues and co-morbidities, including the interaction with acute and chronic physical and mental health problems. Management of Patient Health/Illness: Recognizes the presence of co-morbidities, their impact on presenting health problems, and the risk for iatrogenesis. Management of Patient Health/Illness: Treats and manages complications of chronic and/or multi-system health problems. Professional Role: Coordinates comprehensive care in and across care settings. ASCP GERIATRIC PHARMACY CURRICULUM GUIDE COMPETENCIES Continuum of Care: Participate in interprofessional decisions regarding appropriate levels of care for individual patients. Continuum of Care: Facilitate medication reconciliation across the continuum of care. Prioritizing Care Needs: Develop a problem list and prioritize care based upon severity of illness, patient preference, quality of life, and time to benefit. Prioritizing Care Needs: Identify patients who need referrals to other health and non-health professionals. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 29 CORE COMPETENCIES FOR INTERPROFESSIONAL COLLABORATIVE PRACTICE RR3: Engage diverse healthcare professionals who complement one’s own professional expertise, as well as associated resources, to develop strategies to meet specific patient care needs. RR4: Explain the roles and responsibilities of other care providers and how the team works together to provide care. RR5: Use the full scope of knowledge, skills, and abilities of available health professionals and healthcare workers to provide care that is safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable. RR7. Forge interdependent relationships with other professions to improve care and advance learning. TT3. Engage other health professionals—appropriate to the specific care situation—in shared patient-­‐centered problem-­‐ solving. TT4. Integrate the knowledge and experience of other professions— appropriate to the specific care situation—to inform care decisions, while respecting patient and community values and priorities/ preferences for care. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 30 GERIATRIC CARDIOLOGY CLINICAL PEARLS Medications commonly taken by older patients seeing a cardiologist Coumadin (warfarin) – a potent blood thinner, one of the most effective medication available for preventing ischemic stroke in older at-risk patients (those with hypertension, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, diabetes). o Special considerations in older patients: review complete list of medications (both prescription and over-the-counter) for potential drug-drug interactions with warfarin that might excessively thin a patient’s blood (increased risk of bleeding). Beta-blockers (atenolol, metoprolol [Lopressor, Toprol], carvediol) – lower heart rate and blood pressure by persistently blunting adrenergic response; significantly decrease mortality following a heart attack and in those with heart disease; slow the progression of chronic heart failure (improve exercise tolerance and functional status). o Special considerations in older patients: check orthostatic blood pressures (lying, sitting, standing) to ensure that blood pressure does not drop too much (increased risk of falls). Due to the aging of the sino-atrial node, older patients on beta-blockers tend to have lowered heart rates. May cause depression and anxiety. Digoxin – increases contractility of the heart muscle; decreases frequency of hospitalizations for congestive heart failure but does not lower mortality. o Special considerations in older patients: potential for toxicity is higher in older patients given narrow therapeutic drug window and decreased kidney function associated with aging. Monitor levels more frequently in those with renal failure as toxicity can lead to significant heart arrhythmias. Normal aging changes to the older heart Muscle is less able to relax between heart beats and becomes stiffer over time (especially in those with longstanding high blood pressure). Less able to increase the strength of contraction (and thereby becomes harder to offload more oxygen to the heart muscle during exercise). The walls of coronary blood vessels become less elastic over time. Specific considerations for older patients seeing a cardiologist Patients with heart failure but a preserved ejection fraction – diastolic dysfunction – frequently have a comparable prognosis to those with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (systolic dysfunction). A better prognostic marker for patients with heart failure is to assess their functional capacity, i.e., how limited on a daily basis they are by their shortness of breath. Treating hypertension in patients in their 80s and 90s is still of paramount importance – with resultant risk reduction of stroke and heart failure. You need to be more cognizant, though, of inducing orthostatic hypotension in older patients on multiple blood pressure-lowering agents (especially alpha-blockers and ACE-inhibitors). Beta-blockers are not optimal blood pressure agents when used in isolation. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 31 Anticoagulation with warfarin is currently considered the most effective way to prevent stroke in older patients with atrial fibrillation. Carefully consider a patient’s goals of care when weighing a patient’s risk of anticoagulation with the possible benefits of stroke prevention when starting warfarin. Loop diuretics (furosemide, or, Lasix) are effective for symptomatic relief of congestive heart failure symptoms – but have many side effects in older persons that need to be closely monitored (electrolyte abnormalities). UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 32 GERIATRIC ORTHOPEDICS: CLINICAL PEARLS With the first baby boomer set to turn 65 on January 1, 2011, there will be more older patients visiting orthopedic doctors than ever before. The focus of an orthopedic visit for an older patient is to consider treatments designed to maintain mobility and alleviate musculoskeletal pain that can lead to a loss of daily function. Advanced minimally invasive surgical procedures have decreased the frequency of complications associated with surgery, making surgical intervention a viable option for many older patients. The following are examples of common problems an older patient may encounter: Hip and Femur Hip fractures are the most frequent orthopedic injury suffered by older patients. A patient whose hip fracture is not treated urgently (within 48 hours) is at greater risk of ultimately losing their mobility and independence – which can, unfortunately, lead to long-term care placement. Unless treated urgently, hip fractures are also the orthopedic injury with the highest mortality rate – both immediately following the fracture as well as 6 and 12 months later. There are four patterns of hip fracture frequently seen: femoral head fracture, femoral neck fracture, intertrochanteric fracture, and subtrochanteric (shaft) fracture. Interdisciplinary care is vital for successful treatment. The most important preventative treatment for hip fractures in older patients is fall prevention, focusing on promoting exercise, maintaining balance, and minimizing potentially hazardous medications. Older patients should be screened for osteoporosis (see below); those with hip fractures should almost always be treated for osteoporosis. Knee The knee is a major site for a list of debilitating pathologies, including bursitis, ligament tearing, and highly prevalent arthritic diseases. Knee surgery and even total knee replacement are becoming popular procedures for older patients as new technologies offer a faster recuperation and higher likelihood of recovering full mobility. Foot and Ankle Bunions, tendon rupture, and nerve damage are some foot/ankle problems that can significantly disrupt gait and balance. The foot and ankle is generally divided into three sections - forefoot, midfoot, and hindfoot (including the ankle) - with each area having its own diverse pathology. A comprehensive article about geriatric ankle/foot surgery can be found at the following link: Foot & Ankle Surgery: Considerations for the Geriatric Patient http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/710374 (Lee & Mulder, 2009) Spine Older patients can experience a number of pathologies that affect the integrity of their vertebral column. The diagram at right lists a number of common issues that can cause back pain. Note that the range of problems includes skeletal, vascular, nervous, cancerous, and joint components UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 33 SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR OLDER PATIENTS SEEING AN ORTHOPEDIST Osteoporosis Osteoporosis is a very common medical condition, affecting roughly 10 million older patients. Osteoporosis is marked by bone loss and compromised bone strength, leading to a greater risk of fracture with minimal (or even no) trauma. Hip fractures pose perhaps the greatest risk to an older patient’s independence. Osteoporotic vertebral fractures can lead to chronic pain and loss of function. Treatment of osteoporosis has become much more feasible with the advent of bisphosphonates – namely, alendronate (Fosamax), ibandronate (Boniva), risedronate (Actonel), and zoledronic acid (Reclast). Preventative measures such as calcium and vitamin D supplementation can also help ward off disease progression significantly and even prevent falls. Arthritis: osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis Arthritis is a major issue in older patients, spanning a clinical spectrum from totally asymptomatic to debilitating and incapacitating. Osteoarthritis can be more difficult to treat with medication because its pathology is ‘wear and tear’ aging rather than immune-mediated like rheumatoid arthritis. Exercise, especially in the water (where joints are buoyant), is invaluable. If medications prove ineffective and compromise a patient’s daily functioning, then surgery may be entertained as an option to reduce pain and restore joint function. Rheumatoid arthritis is an inflammatory arthritis that can be treated through the use of anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant drugs. Cancer Various types of cancer can cause debilitating problems. Sarcomas (and soft tissue sarcomas) can infiltrate bone and muscle, devastating normal tissue architecture and functionality. Cancer with metastisis to bone can be a source of pain and potential disability. Blood cancers such as multiple myeloma will also frequently manifest in part through bone lesions. The risk of fracture is greatly increased in any number of cancers. Frailty and Immobility The elderly population is extremely heterogeneous; at any age there will be patients who are frail and in poor health as well as others who are quite healthy and physically robust. (To a geriatrician, a patient’s chronologic age is far less important than their overall functional age.) Recovery from surgery needs to take into account a patient’s baseline activity level. It is often necessary that surgical recuperation occurs in an inpatient rehabilitation facility, or skilled nursing facility. Regardless of frailty, one of the most pressing issues in older patients is extended immobility. Immobility can quickly lead to a severe decline in health, due to problems such as pressure ulcers, infection, muscle/bone atrophy, and heart failure. A main goal of orthopedic surgery in elderly patients should be to maximize mobility as prevention for the problems of immobility. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 34 WHAT TO DO WHEN YOUR PATIENT IS HOSPITALIZED & AN INTRODUCTION TO THIRD YEAR FOR MS-IIS The Navigator Program was designed to accomplish two main goals. The first is providing students with diverse early clinical experiences as longitudinal patient relationships in geriatrics. The second goal is to support older adults by providing them with a resource as they navigate a convoluted and complicated medical system. Often the patients who benefit the most from The Navigator Program are those who depend the most heavily on medical care; in general they are medically complex and frailer patients. Because frail patients face multiple health problems, hospitalization of a Student Navigator’s patient is not an uncommon occurrence. Navigating a hospitalized patient can be logistically challenging since the patient’s interactions with health professionals are not confined to a specific block of time as they are in an outpatient appointment. For some students (especially MS-Is or MS-IIs), a hospitalized patient may be there first experience with inpatient internal medicine. Inpatient care can be as confusing and as daunting for medical students as it is for patients. Below are some general tips regarding what to expect in internal medicine and how to navigate a hospitalized patient. A Day in The Hospital: Hospitalized patients are cared for by a team of medical providers that includes nurses, social workers, attending physicians, specialist physicians, residents, and health profession students The day starts early for patients and medical staff. Generally, residents and medical students will first see patients between 6am-8am. Commonly, the team then regroups with an attending doctor and visits all the patients the team cares for. This is referred to as “rounding”. While all hospitals and teams vary, usually the team solidifies the care plan for each patient while rounding with the attending physician in the morning. Some teams explain the care plan to the patient while rounding, while other teams choose to do so while visiting patients in the afternoon. Nurses check-in on patients at certain intervals throughout the day and are often the first-line interaction patients have when they need something or call for help. How frequently a nurse checks-in on a patient is related to the severity of the patient’s illness, medical needs, and hospital regulations. Throughout the afternoon, medical team members will check-in on patients based on the severity of the patient’s illness and communication from the patient’s nurse. The patient’s care is transferred to a night team sometime between 6pm-8pm; usually there are few changes to a patient’s care plan overnight unless the patient’s condition changes dramatically. Tips for Navigation: Be open and forthright with the patient and caregivers about your schedule. It is unrealistic to try and be present for every conversation between the patient and medical staff. Work with the patient and his/her family to determine how you can be most helpful. Are there certain meetings with medical staff the family would appreciate your presence at? Would it be helpful to visit with the patient on certain days family members are unable to? Nurses are a vital part to the care team and ideally they are involved in the care planning for the patient with the rest of the team. Students may find, however, that communication between physicians/residents and nurses is not always perfect. To find out precisely what the care plan for a patient is, a student may have to discuss what the patient’s understanding is, the impressions and plans from their nurse, and possibly ask a resident or attending for the plan if the opportunity presents itself. Care providers are always busy caring for multiple patients. Use your best judgment in asking the patient’s care team to explain the plan to you. Sometimes the best you can do is talk with the patient. Having a hospitalized patient can feel like a major time commitment and a huge responsibility. It is most important to be reasonable about how often you can be present. Other priorities must come first, including class-time, studying, and downtime away from school or navigator program commitments. The templates provided for this course are intended to help and not hinder navigators; they may not be as effective in the inpatient setting as they are for outpatient appointments. Instead of the templates, navigators may find it helpful to keep a daily log of the patient’s care plan and medications while hospitalized. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 35 MODULE III: GERIATRIC SPECIALTY-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS: GUIDING QUESTIONS Discuss the experience of following patients to settings other than a geriatrician’s office. Be prepared to give other students navigators a brief summary of the visit. How was the experience the same or different for the patient? How about for you as the Navigator? What are the important factors in effectively caring for a medically complex older adult? Using the relevant section(s) of this module, find a few important concepts regarding specialty-specific geriatric care to share and emphasize with the group. How might you envision the treatment the specialist offered varying if the patient was younger or had fewer comorbidities? Do you think the age or health of the patient was a consideration the specialist took into account when making treatment recommendations? UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 36 MODULE III: GERIATRIC SPECIALTY-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS: READING AND REFERENCE LIST AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. The Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50: 205–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.50.6s.1.x Accessed http://www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/2002_persistent_pain_guideline.pdf August 25, 2012 American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons (2009), Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57: 1331–1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x Accessed http://www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/2009_Guideline.pdf August 25, 2012 Fisher A, Davis M, Rubenach A, Sivakumaran S, Smith P, Budge M. Outcomes for older patients with hip fractures: The impact of orthopedic and geriatric medicine cocare. J Orthop Trauma 20(3) March 2006. Gawande A. The way we age now. The New Yorker. Accessed http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/04/30/070430fa_fact_gawande August 25, 2012. Gleich G. 3D Geriatrics: dementia, delirium, and depression. PowerPoint presentation at UMMS CRIT 2010. Accessed http://onlinetraining.umassmed.edu/p97121950 August 25 2012. Guttman M. The aging brain. USC Health Magazine. Accessed http://www.usc.edu/hsc/info/pr/hmm/01spring/brain.html. August 25, 2012. Jansen J, Butow P, van Weert J, van Dulmen S, Devine R, Heeren T, Bensing J, Tattersall M. Does age really matter? Recall of information presented to newly referred patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:5460-5457. Lichtman A. Guideline for the treatment of elderly cancer patients. Cancer Control. November/December 2003; 10(6): 445-453. Nakasato Y, Ling S. Geriatric Rheumatology. Developed in collaboration with the University of Oklahoma Reynolds Department of Geriatric Medicine, 2008. Accessed http://www.ouhsc.edu/geriatricmedicine/Education/GeriatricRheumatology/index.htm August 25, 2012 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 37 M ODULE IV: E ND - OF -L IFE C ARE & C ONSIDERATIONS Summary Our fourth (and final) learning module was developed in response to the unexpected passing of two navigated patients. The “End-of-Life Care Considerations” module is designed to introduce students to the principles of palliative care and hospice – mindful that MS1, MS2, GSN, and pharmacy students do not always receive formal education in end-of-life care. Hospice is an interdisciplinary treatment model for patients with an estimated life expectancy of six months or less. Rather than the curing of disease, the primary goal of hospice is aggressive symptom management – adherent to a patient’s goals of care, with an emphasis on quality of life and alleviation of physical and emotional stress (patient, caregivers). A Medicare benefit, hospice affords services to patients for which they would otherwise not be eligible, e.g., medical supplies, emotional/spiritual counseling, and bereavement support following a patient’s death. Hospice truly models an interdisciplinary approach to patient care, with a physician overseeing the care plan, but with interdisciplinary staff providing much of the hands-on care, including social and emotional support. Surveys have shown that 98% of families whose loved one enrolled in hospice would recommend hospice care to others. Yet, despite such high satisfaction rates, hospice is still underutilized. Despite the six month benefit, the median length of hospice care is only 21-26 days – with ~1/3 of patients referred in the last week of their life. We will begin to further explore these concepts and some of the barriers to hospice enrollment – and consider how to most effectively communicate with patients and their families about hospice care. Part 1 An 86-Year-Old Woman With Cardiac Cachexia Contemplating the End of Her Life http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/303/4/349.full.pdf+html Kutner Part 2 Understanding Hospice – An Underutilized Option for Life’s Final Chapter http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp078067 Gazelle Part 3 On Breaking Bad News and Speaking of Death Cukor Part 4 In the Clinic: Palliative Care http://www.annals.org/content/156/3/ITC2-1.full.pdf+html Part 5 A Geriatrics and Palliative Care Blog http://www.geripal.org On Twitter: @GeriPalBlog UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection Swetz Smith & Widera P a g e | 38 MODULE IV: END-OF-LIFE CARE & CONSIDERATIONS: MEDICAL, NURSING, PHARMACY, AND INTERPROFESSIONAL COMPETENCIES AAMC & JOHN A. HARTFORD FOUNDATION GERIATRIC COMPETENCIES FOR MEDICAL STUDENTS Health Care Planning and Promotion: Define and differentiate among types of code status, health care proxies, and advance directives in the state where one is training. Palliative Care: Assess and provide initial management of pain and key non-pain symptoms based on patient’s goals of care. Palliative Care: Identify the psychological, social, and spiritual needs of patients with advanced illness and their family members, and link these identified needs with the appropriate interdisciplinary team members. Palliative Care: Present palliative care (including hospice) as a positive, active treatment option for a patient with advanced disease. AACN & JOHN A. HARTFORD FOUNDATION ADULT-GERONTOLOGY PRIMARY CARE NURSE PRACTITIONER COMPETENCIES Management of Patient Health/Illness: Assesses the adequacy of and/or need to establish an advance care plan. Management of Patient Health/Illness: Assesses the appropriateness of implementing the advance care plan. Management of Patient Health/Illness: Plans and orders palliative care and end of life care as appropriate. ASCP GERIATRIC PHARMACY CURRICULUM GUIDE COMPETENCIES Continuum of Care: Describe advanced directives, the role of power of attorney, and living wills. End of Life Care: Define the philosophy and processes of hospice/palliative care. End of Life Care: Identify and demonstrate the ability to discuss end of life issues as they relate to medication appropriateness. CORE COMPETENCIES FOR INTERPROFESSIONAL COLLABORATIVE PRACTICE RR4: Explain the roles and responsibilities of other care providers and how the team works together to provide care. CC8: Communicate consistently the importance of teamwork in patient-centered and community-focused care. TT4: Integrate the knowledge and experience of other professions – appropriate to the specific care situation – in shared patientcentered problem-solving. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 39 MODULE IV: END-OF-LIFE CARE & CONSIDERATIONS: GUIDING QUESTIONS Has anyone had a personal experience with hospice that they would be willing to share? What is the difference between palliative care and hospice? What do you think are some of the most common barriers (on the part of patients, families, and physicians) for hospice enrollment? Why are so many patients only referred to hospice in the last week of their lives? How can you effectively communicate with patients and their families about hospice? What are some non-cancer diagnoses which qualify patients for hospice? What are some symptoms that a patient might experience at the end of their life besides pain? What are advances directives? Are you familiar with the MOLST? (http://www.molst-ma.org/) Who are the interdisciplinary members that constitute a hospice team? What are their individual roles in providing care UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 40 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 41 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 42 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 43 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 44 MODULE IV: END-OF-LIFE CARE & CONSIDERATIONS: READING AND REFERENCE LIST Kutner, Jean S., MD, MSPH. An 86-Year-Old woman with cardiac cachexia contemplating the end of her life: Review of hospice care. JAMA: January 27, 2010; 303(4): 349-356. Gazelle, Gail, M.D. Understanding hospice – An underutilized option for life’s final chapter. NEJM: July 26, 2007; 357(4); 321-324. Cukor, Jeffrey. On Breaking Bad News and Speaking of Death. Lecture from “Caring for the Seriously Ill” elective at University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA. Reprinted with permission. Swetz, Keith M., MD, and Kamal, Arif H., MD. In the clinic: Palliative care. Annals of Internal Medicine: February 7, 2012; 156(3); ITC2-1. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 45 R ESOURCES O VERVIEW Additional resources provided to allow the Student Navigator further development and understanding of available assistance to older adults, as well as the challenges motivating the need for the services. Advancing Geriatrics Education at UMMS (AGE) Geriatric Interest Group at UMass Medical School (GIG) University of Missouri SOM Reynolds Geriatric Portal http://www.umassmed.edu/AGE http://www.umassmed.edu/AGE/GIG http://som.missouri.edu/reynolds/links.htm University of Arizona SOM Reynolds Geriatric Portal http://www.reynolds.med.arizona.edu/index.cfm Geriatrics Overview and Housing Options (Bonner) http://onlinetraining.umassmed.edu/p82709042 Examples of Services for Elders in the Worcester Community Elder Services of Worcester http://www.eswa.org 411 Chandler St., Worcester MA 01602 Phone: 508.756.1545 / Toll Free: 1.800.243.5109 TDD: 508.792.4541 / FAX: 508.754.7771 Nutrition & Protective Services Programs [Direct] Phone: 508.852.3305 Home Connections Summit Eldercare & Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) http://www.summiteldercare.org 277 E Mountain St. and 1369 Grafton St, Worcester MA 1.800.698.7566 / TDD/TTY: 1.800.899.4196 National Family Caregivers Association http://www.nfcacares.org/caregiving_resources PROGRAM OBJECTIVES ADDRESSED IN RESOURCES OVERVIEW Consider the complexity of multiple medical co-morbidities, polypharmacy, involvement of family members and or caretakers, and possible cognitive impairment when communicating with older persons in the ambulatory clinical setting. Reflect upon the psychological, social, and spiritual needs of their patients with advanced illness and their family members. UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 46 INDEX Actonel, 34 Advancing Geriatrics Education at UMMS (AGE), 37 Alendronate (Fosamax), 34 Anticoagulation, 32 Arthritis, 34 Association Between Age and Health Literacy in Elderly Persons, 21 Atenolol, 31 Atrial fibrillation, 31, 32 Beta-blockers, 31, 32 Bisphosphonates, 34 Boniva, 34 Calcium, 34 Cancer, 34, 35 Cardiology, 3, 28, 35 Carvediol, 31 Cerebrovascular, 22 Clinical Pearls, 21, 24, 30, 33 Common Problems in Geriatrics for Orthopedic Surgeons, 28 Communicating Effectively Checklist, 21 Communication, 3, 4, 21, 22, 23, 26 Communication, non-verbal, 24 Communication, verbal, 24 Coumadin (warfarin), 31 Delirium, 28, 29, 35 Dementia, 22, 24, 25, 28, 35 Depression, 24, 28, 31, 35 Diabetes, 22, 31 Diastolic dysfunction, 31 Digoxin, 31 Does Age Really Matter?, 28 Drug Therapy in the Elderly, 16 Elder Services of Worcester, 37 Empathic Listening, 24 Family Caregivers, Patients and Physicians, 21 Foot and Ankle, 33 Fosamax, 34 Frailty and Immobility, 34 Furosemide, 32 General Model of a ‘prescribing cascade’, 18 Geriatric Cardiology, 30 Geriatric Cardiology Clinical pearls, 31 Geriatric Competencies, 16, 28 Geriatric Interest Group at UMass Medical School (GIG), 37 Geriatric Oncology, 30 Geriatric Orthopedics, 30 Geriatric Psychiatry, 30 Geriatrics Overview and Housing Options (Bonner), 37 Gleich G, 6, 28 Guidelines for the Treatment of Elderly Cancer Patients, 28 Guiding questions, 6 Guiding Questions, 19, 26, 35 Gurwitz J, 16, 19 Guttman M, 28 Health Literacy and Patient Safety, 21 Hearing impaired, 24 Heart, 31, 32, 34 Heart Disease in the Elderly, 28 Helpful Tips, 10 Hip and Femur, 33 Hood VL, 21, 27 Hypercholesterolemia, 22 Hypertension, 22, 32 Ibandronate (Boniva), 34 Immobility, 34 Impact of Orthopedic and Geriatric Medicine, 28 Important concepts, 6 Important Concepts, 18, 22, 30 Improving Doctor/Caregiver Communication, 21 Incidence and Preventability of Adverse Drug Events, 16 Kidney, 18, 31 Knee, 33 Lasix, 32 Leffler C, 21, 27 Lichtman A, 28, 35 Loop diuretics, 32 Lopressor, 31 Low Health Literacy, 21 Making Medication Use Safer in Older Adults, 16 Managing Communication Challenges, 24 McGee S, 4, 5 Metastisis, 34 Metoprolol, 31 Module I Geriatric Prescribing, 16 Module II Communicating with Elders, 21 Module III Geriatric Specialty-Specific Considerations, 28 Multiple myeloma, 34 National Family Caregivers Association, 27, 37 Note-Taking Template (blank), 12 Note-Taking Template (sample), 14 Nurss J, 21, 27 Oncology, 3, 28, 30, 35 Optimizing Drug Treatment for Elderly People, 16 Orthopedics, 3, 28, 35 osteoarthritis, 34 Osteoporosis, 34 Outcomes for Older Patients with Hip Fractures, 28 Overall Timeline for Student Navigator Training, 11 Paraverbal Communication, paraverval, 24 Parker R, 21, 27 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 47 polypharmacy, 3, 17, 18, 37 Program Faculty and Administration, 5 Program Objectives, 17, 22, 29, 37 Psychiatry, 3, 28 Reading and Reference List, 20, 21, 27, 36 Reclast, 34 Resources, 37 rheumatoid arthritis, 34 Rheumatoid arthritis, 34 Risedronate (Actonel), 34 Rochon P, 16 Sarcomas, 34 Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults, 22 Specialty-specific considerations, 3 Specific Considerations for Older Patients Seeing an Orthopedist, 34 Spine, 33 Stroke, 22, 31, 32 Summary, 6, 16, 21, 28 Summit Eldercare & Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), 37 Systolic dysfunction, 31 Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA), 21 The Way We Age Now, 28 Timeline of a Navigator Session, 8 Tjia J, 16 TOFHLA, 21, 22, 27 Toprol, 31 Training to Become a Student Navigator, 6 UMMS Advancing Geriatric Education (AGE), 6 University of Arizona School of Medicine Reynolds Geriatric Portal, 37 University of Missouri School of Medicine Reynolds Geriatric Portal, 37 University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics Medication Reconciliation, 16 Vallie B, 3, 10 Vertebral column (diagram), 33 Visually impaired, 24 Vitamin D, 34 Warfarin, 31, 32 Williams M, 21, 27 Young L, 28 Zoledronic acid (Reclast), 34 Zweig S, 28 UMMS AGE Senior Patient Navigator Program© Materials included may be subject to copyright protection P a g e | 48