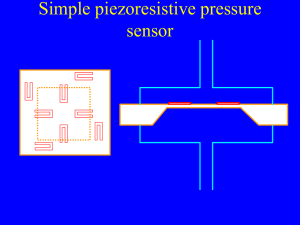

A Thesis entitled Design and Fabrication of a Micro

advertisement