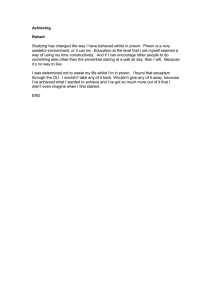

Children Imprisoned by Circumstance

advertisement