1 CHARLES KNIGHT AND THE EMERSON ELECTRIC COMPANY

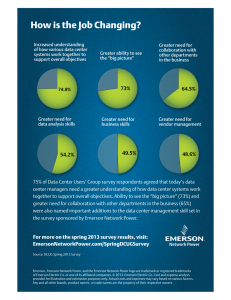

advertisement

CHARLES KNIGHT AND THE EMERSON ELECTRIC COMPANY ( This profile is based on two company sponsored histories, one written by Charles Knight and the Other written while he was CEO) The Emerson Electric Company was founded in St. Louis in 1890. The founders were two Scottish inventors and a wealthy local investor. Their vision was to invent and manufacture a variety of electrical products, beginning with motors that powered electric fans. The company prospered for three decades and then entered a long period of financial struggles beginning in 1920 and lasting up to World War II. That war gave the company new life as it secured contracts to manufacture artillery shell components and gun turrets for bombers. After the war the company continued to prosper but by 1953 it was still a medium size company which manufactured fans and electric motors in addition to its defense contracts. And its profitability was in question. In 1954 a new chief executive officer, W.R. “Buck” Persons, was hired. Under his leadership, from 1954 to 1974, Emerson expanded and diversified. It became a large corporation with most of its activity confined to the United States. That accomplishment occurred during a time of peace and prosperity in the United States. In addition to his successful growth strategy, Persons led the search for a successor would keep the company on a strong growth trajectory. His hand-picked successor was Charles “Chuck” Knight. The company’s board of directors approved because it expected Knight to retain the Persons success formula. As CEO Knight retained the company’s focus on management process as the key to everything else. He succeeded in maintaining the company’s growth during the period 1974 –2000 and in the process made Emerson a truly global corporation. That accomplishment occurred during a time of domestic and international turmoil. Under Persons and Knight the company achieved 43 straight years of increases in earnings and earnings per share. Six months after David Farr succeeded Knight as CEO the company had to announce the end of that streak due to a sharp drop in revenue. The Knight story is one of tough challenges and generally successful responses: 1. 2. 3. He concluded that the product portfolio he inherited would not support the company’s growth targets. So he stepped up the acquisitions process using a new strategic planning function to identify targets. He concluded that Emerson’s market shares were too small to produce the superior financial results that were the company’s targets. So he adopted a goal of using acquisitions to achieve large market shares. He discovered that with globalization the U.S. was losing its status as the standard for performance. So Emerson adopted international benchmarking 1 4. He concluded that the company’s policy of being a close technological follower put it at a competitive disadvantage. So Emerson adopted the goal of being the technological leader in all of its divisions. He discovered that the increasing size of Emerson made it necessary to institute new methods of planning, communicating , controlling and management development. So Emerson’s vaunted management process was modified accordingly. He found, in the 1990s, that investors were changing their criteria for evaluating stocks. So Emerson modified its financial planning accordingly. 5. 6. The rest of the Persons-Knight story follows. I. A CLOSER LOOK AT BUCK PERSONS’ TENURE: 1954-1973 Prior to coming to Emerson, Persons worked at the Lincoln Electric Company as vice president and general sales manager. Persons was an engineer by training and a gifted salesman by nature and experience. And he achieved great success at Lincoln by exercising those skills. That record led Emerson’s board to believe that Persons would be able to arrest Emerson’s downward profit trend. Persons officially became Emerson’s CEO on January 1, 1954. His experience at Lincoln Electric led him to immediately evaluate Emerson’s manufacturing costs and pricing, both of which were found wanting. A consultant was brought in to help with the analysis. The findings resulted in a reduction in the number of products being manufactured, a detailed look at the actual costs of making and marketing each product, and a change in pricing so that all products were profitable or discontinued if they could not be successfully priced at profitable levels ( Emerson Electric Company, p. 142). Persons’ first year on the job was made more stressful by difficulties with the company’s labor union. The union was used to asking for and getting periodic wage increases and 1954 was a year when an increase was demanded. Persons tried to convince the union that an increase would cripple the company. He shared the company’s financial information with the union to make the case. He pointed out that competitors had opened new plants in low wage areas, giving them a 50 to 90 cents an hour wage advantage over Emerson. He pleaded with the union to accept a 10 percent REDUCTION in wages to enable Emerson to, “ rebuild the company’s sales organization, reengineer all Emerson products for lower costs, to introduce new ‘non-seasonal products to level out employment,’ and to reexamine manufacturing operations.” ( Emerson Electric Company, p. 143). The union did drop its demand for a wage increase but asked for a profit-sharing plan instead. Emerson agreed in principle but asked for time to work out a plan. The union tried to force quicker action by calling a work stoppage on September 20th. Persons saw the strike as a power struggle to, “ …decide who was going to run the business.” ( Emerson Electric Company, p.144). The strike lasted 10 weeks and ended when the company agreed to a one year experiment with a profit sharing plan. 2 Persons viewed the strike as a breakdown in communications and launched an effort to meet with all employees and reestablish good communication. Eventually he added a monthly opinion survey of all employees at each of Emerson’s locations. But Persons also concluded that the company would have to move its production of motors to locations with lower labor costs. That decision was communicated to the employees and soon thereafter Emerson found a low cost labor site in Paragould, Arkansas. The new Emerson plant opened there in 1956 and by 1960 labor costs per hour at Paragould were $ 1.60 per hour compared with $ 2.40 per hour in St. Louis. The Paragould success was followed by the opening of additional plants in other low cost labor areas. Decentralization became a key part of Emerson’s new competitiveness strategy. The decentralization process caused Persons to reevaluate the “quality of the management process” at Emerson ( Emerson Electric Company, p.150). He was particularly concerned about finding ways for company managers to promote constructive change. The boldest action he took to address this problem was his decision to take small groups of managers with him on week-long ore boat trips. The boats carried iron ore from Minnesota to Chicago. They had room for eight paying passengers. The one-week trip isolated the passengers from their daily routines and gave them plenty of time to talk with one another. Persons expected cost cutting, product quality improvements and better pricing to boost Emerson’s profits. But he did not believe that those actions alone would be sufficient to guarantee long run success. His instincts told him that Emerson needed to become a big company and to do so through diversification. In 1955 the consulting firm of Arthur D. Little was hired to study Emerson’s growth needs and options. Little concluded that Emerson would have to achieve growth through diversification in order to meet the company’s profitability targets of a pretax profit of 12 percent on Electrical Division products ( 2 percent at the time of the study) and 8 percent in the Armaments Division ( less than 1 percent at the time). Persons considered internal diversification through research and development. But past experience led him to conclude that an easier approach, and one more likely to succeed, would be through acquisitions. And so Emerson added another element to its growth strategy – acquisitions. The first acquistion took place on April 1, 1957 and it triggered a major strategic decision regarding how Emerson should manage its new acquisitions. The acquired firm was Pryne and Company, a California firm that made kitchen ventilator units. Pryne’s founder, Ralph Pryne, planned to retire and wanted to sell his business. But he also had great pride and affection for his company; he wanted it to continue in existence; and he wanted it to maintain its identity. Emerson honored that desire and closed the deal by agreeing to run Pryne and Co. as a separate entity with its identity intact. Making that decision was not easy. Emerson’s advertising agency, a highly respected firm, recommended that Emerson put the corporate brand on the acquisition, as was common practice in American industry in those days. After agonizing over the decision Persons 3 and his team decided to not only agree to Pryne’s request but also to make that approach the corporate policy. As Persons put it, “ We were buying product names that had a very distinct position with customers. We were buying organizations that we didn’t intend to throw out. We wanted to help them grow and become more sophisticated…If we had simply consolidated these acquisitions, they would have been lost, and the opportunities in those businesses could not have been recognized. That was the whole purpose of the divisional concept.” Thus was born Emerson Electric’s adoption of the “independent” divisions strategy for acquisitions. The Emerson acquisitions strategy emphasized focusing on areas where the company already had a strong knowledge base --- electric, electromechanical, and electronic businesses. ( Emerson Electric Company, p. 156) Two of the company’s next three acquisitions reflected that emphasis. The three were Day-Brite ( commercial lighting), White-Rodgers ( a leading manufacturer of thermostats and gas controls for furnaces and appliances), and U.S. Electrical Motors ( integral horse power electric motors). What might be considered the three most important acquisitions in the 1960s also fit that mold. The three were: Ridge (a leading manufacturer of professional hand and power tools for plumbing, industrial, electrical and commercial markets); In-SinkErator ( a leading producer of household waste disposers); and Browning ( a leading manufacturer of mechanical power transmission products). A total of three dozen acquisitions were made during Persons’ years as C.E.O. (Emerson Electric Company, p.170).In addition, the Armaments Division had its name changed to the Electronics and Avionics Division in 1955 ( Emerson Electric Company, – p. 172). While acquisitions became a key or perhaps the key to Emerson’s growth, the internal development of new products was also important. The first major success in this area during the Persons era was the development of a radial-arm saw. Introduced in 1956 this product enabled Emerson to capture a large share of the business of the major retailer Sears. In fact, by 1963 that business was so large that Emerson began construction on a new factory to specialize on power tools for Sears. Emerson’s approach to new product development was to encourage the divisional managements to take the lead. However, Persons thought that corporate headquarters ought to play a supporting role. That view led him to establish several specialized research and development laboratories at the corporate level. As Emerson grew rapidly Persons found himself spending most of his time on planning, controlling and communicating. Doing so was complicated by the need to change the company’s management structure and processes in step with the changes in size and complexity. While most of Persons’ time was devoted to management matters, he did find time to engage in important marketing efforts. He, himself, had been an outstanding salesman at Lincoln Electric and he was a firm believer in devoting top management time 4 to key accounts. And so he made it a practice to personally court the top management of some of Emerson’s key accounts. Persons’ final contribution to Emerson’s success was to ensure outstanding successor management. In the early 1970s he decided to put a successor in place by no later than 1975 when he, himself, would be 65-years old. A search was launched and two consulting companies were hired to pare an original list of a hundred candidates down to six. One of the consultants was Chuck Knight who had consulted for most of Emerson’s divisions, sat on the Motor Division’s board and had extensive foreign experience. When Persons found himself dissatisfied with all of the final six he offered the job to Knight. Knight at first turned him down but was finally convinced. The Emerson board of directors elected him vice chairman of the board on December 5, 1972 and in October 1973 he become C.E.O. Persons remained as chairman until the summer of 1974. Knight’s selection was made in spite of a concern on the part of the board about Knight’s age. He was only 37 years old at the time. But that was offset by his deep knowledge base and by the assurance that he would, “ come in and operate this company with the policies and approaches that have proven so successful,” so that Emerson will have, “ the continuation of a winning formula.” III. A CLOSER LOOK AT CHUCK KNIGHT’S TENURE: 1974-2000 Chuck Knight was raised to be a business leader. His father, Lester Knight, was a Chicago area engineer who had founded a successful consulting company, Lester B. Knight and Associates. The father had a vision of Chuck eventually taking over that company and so, early on, he began mentoring and testing Chuck by giving him a series of business assignments. The summer following Chuck’s freshman year in high school he worked as a laborer in a plaster mould company owned by his father. The next summer he worked in a Canadian metal foundry; and during his college years Chuck spent summers at different jobs ranging from a Chicago roofing company to a diesel engine plant in Europe and a steel mill in Argentina. After Chuck received an M.B.A. degree from Cornell University he was sent to Germany where he worked in an entry level management job at a German supplier of automobile parts. In 1961 Chuck was named head of the European subsidiary of Lester B. Knight International Corporation. That job involved, in Chuck’s words, “ a lot of organization studies, a lot of foundry work, a lot of plant work .” ( Emerson Electric Company, p.190). In 1963 Lester Knight gave Chuck his first consulting assignment with Emerson. Chuck’s job was to help Emerson digest a newly acquired firm, U.S. Electrical Motors. Numerous other consulting jobs with Emerson followed, culminating in Chuck being assigned to help Persons select the next Emerson C.E.O. 1. Knight’s Immediate Challenges 5 True to the expectations of Persons and the board of directors, Knight recognized and valued the beliefs, values and skills which had taken root at Emerson during the Persons years. Knight regularly talked about them, cited them as key elements of the corporate culture, and practiced what he preached. A strong believer in lists, Knight identified what he believed to be Emerson’s key beliefs and values in a book he co-authored in 2005. That list referred to the situation during his tenure as C.E.O. but can be considered a reasonably accurate statement of the situation when he began. That list consisted of: (Knight, pp.4-6): • • • • • • • • • • “We insist on integrity in everything we do. Emerson’s reputation is priceless, and we have zero tolerance for misconduct or malfeasance. Not only is this ethically the right thing to do, but we also save time and expense by operating on the basis of trust – among managers, between managers and employees, and between the company, its board, its investors, customers, suppliers and partners.” “Our board, investors, customers and employees all want the same thing: consistent high performance.” “Profitability is a state of mind. To achieve winning results over the long term we must consistently generate high profits. We believe we can do this if our people are fully committed, focused, disciplined and willing to work hard.” “Finding new ways to add value for customers is the path to success.” “We must be the industry leader in our key markets. As number one we are in the best position to leverage our scale, manage costs, and invest for continued growth and profitability.” “The key to market leadership is technology leadership” “Maintaining a strong balance sheet is a powerful competitive advantage” “Long-term success requires a committed organization.” “Key managers must have autonomy to perform at their best.” “We can improve productivity only through people. Their contributions of ideas, energy and enthusiasm – their commitment – are essential to our ability to achieve constant improvement in everything we do. It is management’s responsibility to create an environment where people can make a difference.” That admirable list not withstanding, Knight took command at a time when Emerson faced a number of challenges. Knight’s list of the top priority issues included (Knight, 2005, p. x): • • • The company’s portfolio of businesses was concentrated in mature industries not likely to achieve outstanding growth. The company’s international presence was inadequate. Only twelve percent of sales came from outside the United States. In spite of the value given to technological leadership, the fact was that,“ Our technology was weak. We were a fast follower, but we needed to change the game to build leadership and transform our technology base from mechanical and electromechanical technologies to electronics.” 6 • • Acquisitions had diminished due to fears of government antitrust actions. The management process needed updating, including adoption of a formal process to produce a long run strategic plan (Emerson Electric Company, p.195). As Knight once put it,“ I admired and wanted to keep the lean organization and small-company informality but also recognized the need for more rigor, discipline, and professionalism at all levels of management. We had to find a way to develop new management talent and keep the pipeline filled. To get the kind of performance we were looking for ---above-average profitability sustained consistently year after year without compromise – we needed to engrain new ways of working (Knight, 2005, p. x). Knight served as CEO for 27 years. During that time sales rose fifteen-fold while net earnings grew eighteen-fold. “Meanwhile,” as he put it,“ we transformed the company under the guidance of an outstanding group of managers…We revamped our portfolio, building strong business platforms that are world leaders in technology. We took the company global and established leadership positions in every major region as well as an international manufacturing base that is the world standard for efficient, bestcost operations. We forged deep relationships with our customers; we no longer provide them simply with good products at attractive prices but with high-value services and solutions that enable them to compete more effectively on a global scale.” (Knight,2005,p.xi) 2. Modernizing and Managing the Vaunted Emerson Management Process Knight tirelessly explained Emerson’s success during his tenure as due first and foremost to what he calls “the management process” which originated in the 1950s. Knight claimed that the management process enabled Emerson to,“ develop superior strategies at all levels of the company” and to, “ execute them with discipline and intensity.” ( Knight, 2005, p.3). The management process was energized by the ten values cited earlier ( “We insist on integrity in everything we do”, etc.). Knight describes it as having six key elements (Knight, 2005,p.7): 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Keeping things simple A commitment to planning A strong system of follow-up and control An action orientation throughout the company An emphasis on operational excellence Creating an environment in which people can and do make a difference Knight devoted a significant portion of his time to managing and modernizing the management process. One of his earliest actions was to modernize key element number 2 ( a commitment to planning) by creating the corporate level job of assistant vice president – strategic planning. He promoted Joe Adorjan to that position and asked him to guide Emerson in developing its first long run strategic plan. 7 3. Getting things done Knight took great pride in Emerson’s ability to “get things done. As he once put it, “ We’ve designed our organization with a bias toward action, where communications flow around problems and projects, where decisions are made at the level where the best information is available, and where a small, talented staff adds high value but doesn’t slow down or get in the way of operating management.’ ( Knight, p. 53). He went on to list the following “Three Tests of an Action-Oriented Organization (Knight, p.55): (1) The organization must plan and control profits at the same level and that level must be as close to customers and markets as possible. (2) Corporate staffs should be kept small (Because. “Large staffs tend to foster a political environment in which the objective is to stymie positive change.”). (3) “Communication should flow directly between and among people who need to know and can execute plans. ( “If information runs primarily through official channels, beware.”). At the middle to upper level management level, Emerson’s planning cycle played a major role in the communication process. It enabled Knight and other corporate level leaders to communicate strategies and decisions face to face and to get immediate feedback. The planning process also enabled Knight to get to know hundreds of managers in all divisions. At the operating level Emerson’s “getting things done” communication process was dubbed “communicative management.” Knight once explained the term as follows (Knight, p.57): “ (Communicative management) is distinct from participative management which to some observers implies a kind of workplace democracy that, taken to an extreme, can paralyze an organization. As the term implies, communicative management is about two-way communications – explaining what we’re doing and why and listening to and acting on employee ideas and concerns. Doing this effectively requires a decentralized approach. We invest heavily in two-way communications including requiring managers at all levels to hold frequent face-to-face meetings with the people working for them.” The key to effective “communicative management” and a “bias toward action” is the selection and nur turing of managers. Management development was therefore one of 8 Emerson’s major concerns under both Parsons and Knight. During Knight’s tenure that policy was driven by the following four principles ( Knight, p.60): “ 1. Talented managers are assets of the corporation – not of the divisions or other units in which they happen to work.” 2. The corporation has the obligation to create opportunities for these managers. 3. These opportunities will involve job rotation and stretch assignments. We don’t move people based on their credentials and experience but rather on their success in prior jobs. 4. Our managers have the obligation to create their own careers. We provide opportunities and it’s up to our people to take advantage of them.” It might be expected that such a set of principles would cause a certain type of individual to be drawn to a management career at Emerson, and that was the case according to Knight ( Knight, p. 64). The type of person attracted to Emerson might also be expected to place a high value on being well compensated for performance. And that was also the case. Managers were rewarded with a combination of salary plus both short term and long term incentives. Knight claimed that, “ Emerson’s approach…puts a significant portion of compensation at risk – more so than is typical at other large companies.” (Knight, p.66). The compensation approach for division level executives during Knight’s tenure was (Knight, p. 66): 1. Short term – A base salary plus a year-end bonus based on the year’s performance. 2. Long term – “ Three types of stock compensation …designed to reinforce performance targets, retain key executives, and reward performance. About three thousand managers are eligible for stock options which are discretionary awards made every two or three years.” With so many managers on Emerson’s payroll, there had to be significant variations in leadership styles. Nevertheless, Emerson’s system encouraged some basic commonalities. Knight’s view of what those leadership commonalities should be appeared in a 1980 Time magazine article. That list consisted of (Loeb, p.82): 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Set priorities. Don’t delegate tough problems. Set and demand high standards of excellence. Have a sense of urgency. Pay attention to details. Be committed. Don’t waste time worrying about things you can’t do anything about. Have the ability to fail. “You cannot innovate unless you are willing to accept some mistakes.” 9 9. Be tough but fair with people. 10. Have fun. “You can’t accomplish anything unless you’re having some fun.” Item number nine of the above list was a signature part of Knight’s interactions with his managers. Particularly in planning conferences he was particularly aggressive in asking questions. But he was fair and it appears that in general the managers accepted or even admired Knight’s approach. 4. Technological leadership Being a close technological follower worked well for Emerson during the Parsons years. That appears to have been the right strategy for those times. But Emerson’s competitive environment seemed to be changing when Knight became CEO and he therefore adopted a new strategy of technological leadership. The result was a technology management process described in detail in Knight’s 2005 book and summarized as follows ( Knight, p. 3): “Emerson transformed itself into a technology leader through our management process. We start with shared beliefs about the importance of the objective, including a high-level commitment from the board of directors and the top executive team. Then we set stretch goals, plan how we will meet them, track and control our progress and pay for results. We are selective and disciplined in limiting spending to programs and projects that are likely to yield new products and to help us in the relatively near future. Thus we focus on applied technology…We provide special funding for programs and projects that are beyond the means of a single division. We open new channels to outside sources of critical technologies. We integrate stand-alone products across divisions into higher-value customer solutions. We champion new technology projects and support them with corporate resources. Finally, we honor achievements.” Initially Emerson’s technology development efforts were focused in the United States. But as the company transformed itself into a truly global corporation, spending on technology efforts began to be located in other countries. In the mid-1990s the process of overseas siting of technology spending arrived in China. There Emerson not only financed research and development projects but also sponsored PhD programs (Knight, pp. 131-132). 5. Operational Excellence One of Knight’s proudest accomplishments was Emerson’s success at achieving relatively high profit margins. As he put it in his 2005 book ( p. 88): 10 “Emerson is renowned for achieving consistently high profit margins. We strive for consistent high profitability because it is essential to creating shareholder value…During the past two decades, our average profitability, measured as earnings before interest and taxes as a percentage of sales, has run 30 percent higher than that of a group of peer companies…We’ve done this through good times and bad, continually finding ways to maintain profit margins in spite of pricing pressures, competition, inflation, the dilutive impact of acquisitions ( most of which had lower margins than Emerson), the costs of maintaining technology leadership and other factors. Our ability to deliver high profits consistently is a function of operational excellence.” Persons had introduced the emphasis on continuous efforts to reduce costs . Cost reduction was Emerson’s “religion” in the 1960s and 1970s. As Knight explained, “ (W)e implemented an aggressive program of cost reductions. Through our annual planning process, we established profit margin targets by division and product line. We also identified the amount of cost reduction necessary to close the gap between available price increases and inflation in our cost factors (hourly and salaried compensation, materials and overhead costs). Before the year started we specified programs and steps to meet 70 percent of our annual cost-reduction target, with the remaining 30 percent identified and implemented during the year.” ( Knight,p.89). Emerson was so successful with that approach that the company was caught by surprise when it lost a long established hermetic motors contract to a Brazilian competitor. It turned out that the Brazilians had licensed European technology and with their lower labor costs and efficient management were able to beat Emerson’s prices by 30 percent. Looking back on that shock, Knight remembers, “ Not only did we lose a big, long-standing business, but also we were forced to close our hermetic motors operation in Oxford (Mississippi). We lost hundreds of hourly jobs and a significant number of salaried jobs, at both the plant and in division headquarters in St. Louis. We determined that such an experience would never happen again. We also learned two lessons: first, we could no longer take for granted that we were the cost leaders in our markets ; and second, we would have to keep a close eye on foreign competitors and realign our cost structure, as required, in time to prevent the complete loss of other product lines.” (Knight, p. 91). Emerson’s response to that shock evolved in several directions. One was to change the company’s competitive benchmarks from “best in the United States” to “best in the world.” (Knight, p.92). Another was to adopt a new cost reduction strategy. The new strategy was called the Best Cost Producer Strategy. “The idea was not to compete exclusively on price but rather on value – the optimum combination of products, services and pricing – as perceived by our customers: best cost, not lowest cost.” (Knight, p.92). 11 Another part of Emerson’s response was a decision to begin moving production to locations outside of the United States. “Managers in many divisions initially resisted moving jobs. They were concerned about the cost and risk of establishing new, offshore facilities as well as the impact on the welfare of U.S. employees. However, as increasing global competition forced (Emerson’s) prices down in a broad range of products, the economic case for relocation became overwhelming.” ( Knight, p.94). Between 1983 and 1988 Emerson closed fifty plants in the United States and moved production to lower cost countries, particularly Mexico. The experience in Mexico justified those moves. As Knight reported ( Knight, p. 95): “ (W)e found that after an initial start-up period our new Mexican plants achieved quality and productivity levels equal to or better than those of our U.S. plants. This performance reflected the wage and salary differential between Mexico and the United States… A degreed engineer in Mexico cost only 25 percent of the annual compensation of a high school graduate in the United States, whereas a Mexican vocational high school graduate with a thorough knowledge of math and blueprint reading cost only 15 percent of a counterpart north of the border.” Relocation continued in the 1990s. The fall of communism in Eastern Europe presented an opportunity to set up operations in that area. Plants were also located in Asian countries, including a major thrust into China. The result was described by Knight after retirement as follows ( Knight, p. 107): “In the early 1980s we had basically no meaningful hourly jobs in low-cost countries, but after twenty years of continually investing in such locations, nearly 40 percent of our hourly employment was in low-cost areas helping…to contain hourly compensation inflation to approximately 1 percent. This compares with 3-4 percent in hour remaining U.S. plants.” In those remaining U.S. plants there was also a new order. Again, as reported by Knight ( Knight, p.107): “ Armed with facts regarding the realities of global competition and education gained from profit reviews, plant managers and HR professionals communicated the need for change and moderation to our traditional workforce. The average rate of annual general wage increases in the United Statees, for example, fell from 4 percent to less than 3 percent. We made lump sum payments in lieu of general wage increases in alternative years. Two-tier wage structures were introduced and the use of temporary employees was expanded. Medical plans were redesigned, and employee copays were increased…Despite these tough actions, 12 our opinion survey scores actually went up, a testament to the tremendous strength of our communication policies and to our people’s understanding of the challenges we faced.” The relocation of plants outside of the United States enabled Emerson to maintain its profitability edge in the 1980s. But the situation changed in the 1990s as global competition put such strong pressure on Emerson’s margins that the company changed its profit planning process. The new process was named “the profit waterfall”. Essentially it was a tool which tried to identify, in more detail than before, all of the variables that affected profits. Forty-five exhibits were needed to do that. (Knight, p.97). One final example of operational excellence during Knight’s tenure was Emerson’s adoption of a new focus on procurement and supplier relations. This began in the late 1980s and was reflective of a general trend in American management circles at the time. One element of the new approach was Emerson’s adoption of the then popular concept of “lean manufacturing.” That was done with Knight’s typical commitment to be one of the best in the world at using the approach. Related to these changes was Emerson’s decisions to become expert at using the internet to conduct “E-Business.” All of those efforts are reported with some pride by Knight in Performance without Compromise ( Knight, 2005). 6. Acquisitions Knight inherited a company addicted to acquisitions and proceeded to accelerate the process while imposing on it a tighter strategic discipline. Between 1973 and 2000 Emerson completed more than 200 acquisitions, representing an investment of over $ 10 billion. The subsequent performance of the acquisitions was, in general, outstanding. Knight reports that for businesses acquired and owned for five years or more the internal rate of return on the acquisitions averaged 15 percent annually.(Knight, p.143) .That history began after a brief pause. As explained by Knight ( Knight, p. 145): “ Emerson became an active acquirer in the mid-1950s. Between 1957 and 1970, we bought more than twenty companies …In 1970, we essentially stopped doing deals of strategic significance. Our longtime counsel advised the board that major deals faced increasing scrutiny from federal antitrust officials. Emerson shifted its focus to small deals to extend its product lines and gain access to new technologies.” Soon after I became CEO in October 1973, it became apparent through the planning process that Emerson would not be able to maintain healthy earnings growth without restarting the flow of large deals… We became more active in mergers and acquisitions almost immediately…We differ… from many active acquirers. We buy exclusively for the long 13 term. We are not a holding company that makes money through financial engineering but rather an operating company that owns certain types of business in which our participation can add significant value. We are especially interested in the quality of management and organization in the companies we acquire because they are critical to the success of our post-deal integration strategy.” Emerson’s seven guiding principles for acquisitions during the Knight years were ( Knight, pp. 146 – 153): 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. “All Acquisitions Require Top Management Involvement” “ Every Transaction Must Have a Sponsor” “No Transaction Proceeds Without a Plan” “ The Emerson Management Process (Must Create) Value” “ Ego Has No Place in Deal Making” “ Acquisitions Are About People” “ Never Stint on Due Diligence” Among the 200 plus acquisitions made during Knight’s tenure, several are worth citing because of their particular impact on Emerson. Rosemont, Inc , a leader in pressure sensors, was acquired in 1976 and became the basis of Emerson’s subsequent expansion in the area of process management.. In the 1970s Emerson acquired Copeland Corporation, a leading manufacturer of compressors with a revolutionary new technology in development ( the scroll compressor). That acquisition allowed Emerson to become a leader in the compressor industry. In 1987 Emerson acquired Liebert, a leader in the business of controls for temperature and humidity. That acquisition became a catalyst for Emerson’s expansion in the power management business. ( Knight,205,pp. 40-44). 7. Growth in the 1990s In the 1990s Knight and his team recognized a growth challenge and took actions to deal with it. Up to 1992 the company’s strategy was to grow through new products, acquisitions and global expansion and the planning process that directed those efforts was as follows ( Knight, 2005, p. 184): “In our planning process we…relied on a tool called the sales gap chart. It displayed current sales and made projections for the next five years based on an analysis of the sources of growth: the market’s natural growth rate, the division’s change in market penetration, price changes, new products, product line extensions, and international growth. The idea was that if projected growth did not meet or exceed our target, the division would face a gap. Then it became division management’s job to tell us the specific steps it would take go close the gap.” 14 This produced satisfactory results for years, but by the early 1990s it was decided that more needed to be done. One reason for the change in thinking was that Emerson was planning for a ten percent a year growth rate but some peer companies were getting 12 to 15 percent growth rates. Another reason was that growth was slowing at the level of the existing continuing operations of the company. A third reason was a report from Emerson’s task force formed to look at opportunities for growth. One immediate result of the new concern for growth was to divide the divisional planning conferences into two separate sessions – one devoted to growth planning and the second focusing on profit reviews. The reasoning was that when both subjects were handled at one conference, growth planning did not receive adequate attention. (Knight, 2005, p.186). The result of that change, between 1992 and 1997, was a proliferation of growth programs initiated by the divisions ( nearly 1,000), many of which received corporate funding. Then, in 1997, acting in part on the advice of consultant Gary Hamel, Emerson decided to coordinate marketing efforts across internal company boundaries. One result of the new thinking was a change in branding. Knight describes some elements of that decision as follows ( Knight, 2005, pp.193 ff): “ It seems obvious, but every great company must be skilled at understanding customers. That starts with excellence in marketing, a discipline historically undervalued at Emerson. However, our timing for addressing the issue proved fortuitous. New information technology was revolutionizing the discipline, enabling new ways to communicate with customers and enhancing the prospects of building deep, abiding relationships with them…” “We had a collection of divisional brands, most of which were not identified with Emerson. This diverse collection limited our ability to pursue initiatives with customers. At the same time, it hampered our corporate image. I had long been frustrated that Emerson did not receive the recognition it deserved as a technology leader, for example, because our achievements were closely identified with particular divisions.” “ But despite the good reasons to elevate the corporate brand, I was initially skeptical. For twenty-five years I had attached substantial value to acquiring dozens of companies with great brand legacies. Brands like Rosemont, Ridgid and Liebert were widely recognized as industry leaders. I worried that amplifying the Emerson identity could compromise the identify and autonomy of our individual lines. So we approached changes to our brand architecture carefully and deliberately.” 15 The result of that careful approach was a new corporate logo that, “ gave our managers a platform and a kind of permission to work together across our traditional organizational boundaries.” ( Knight, 2005, p.195). There were other changes in Emerson’s marketing approach. One was an educational program named Industrial Strength Marketing, “through which we rotated our top nine hundred managers…(T)he program not only opened our eyes to new ways of marketing but also provided a road map for change.” ( Knight, 2005,p.196). Another change was the so-called “marquee account” program. “(T)he program organized account teams that focused on particular global customers, putting Emerson resources in place that cut across our organizational boundaries. The purpose was to allow the customer to see Emerson as a single integrated supplier rather than a collection of independent divisions, each with a unique approach.” ( Knight, 2005, p.197). 8. Successor management In many ways, Knight followed Persons with respect to successor management. One important difference was that Persons had felt a need to look outside of the company whereas Knight believed there would be ample good candidates within existing management ranks. Emerson’s management development program under Knight had seen to that. One way in which Knight followed Persons example was with respect to the matter of how soon to make the changeover.. In 2005, Knight had this to say about a long tenure for a CEO ( Knight, p.2007): “ Emerson has had only three CEOs in the past fifty years..This leadership continuity is an enormous advantage for Emerson. It reinforces the consistency that we seek and limits the possibilities of our making unnecessary changes in direction or policy. It also sets senior executives’ expectations and dampens organizational policies. When CEOs take over at a relatively young age and serve long tenures, there is less jockeying for position than in the senior ranks of many big corporations .Rather, the senior people at Emerson are more focused on doing their jobs without giving much thought to whether one day the will become CEO.” With that history in mind, Knight began the search for his successor in the mid1990s. The goal was to find someone who knew the company inside and out and who was young enough to “leave a mark.” That had been the approach used by Buck Persons and it appealed to Knight. The company had a deep pool of management talent and that’s where the search began. Eventually the list was narrowed down to four candidates. Out of that group David Farr was chosen. Farr was forty-one years old, had joined Emerson straight out of an MBA program and distinguished himself as he moved up through the ranks eventually becoming group vice president of industrial components and equipment. 16 Farr succeeded Knight in October 2000. Over the next seven years Farr fully justified his selection, even though his tenure began with a revenue drop so sharp that the forty-three year streak of annual increases in earnings came to a halt. From 2001 to 2007 Emerson’s sales per share rose from $18.44 to $28.40; earnings per share rose from $1.20 to 2.66; and net profit overall rose from $ 1.032 billion to $ 2.136 billion. Key to that performance was Emerson’s on-going globalization strategy. In 2007, for the first time in Emerson’s history, international markets generated more revenue than the U.S. II. CONCLUSION On the record, Chuck Knight and Buck Persons formed a mutual admiration society. In Emerson’s one-hundredth anniversary publication Knight was quoted as saying this about Persons (Emerson Electric Com;pany, p.193): “ He took a weak company and made it a great one. Granted, I guess I’ve reaped some of the benefits of that. The base was in place and then we were really able to expand it, but he put a lot of fundamentals in place … The whole drive for cost control, the move to the South that he made, when he made it. That was very strategic. His whole acquisitions program was very successful. I think by any measure you must say he did an excellent job in acquisitions. His view of the need to get going in international business. The concept of planning conferences, the divisional autonomy ---all these are fundamental.” Knight added that Persons ran an outstanding transition process. As Knight put it, “ Buck gave me free rein. I had been working so closely with him on people problems and actually helping him in our recruiting, that the transition, organizationally and peoplewise, was probably the easiest part of the operation. Persons demonstrated his overwhelming support to make it work,…(including) his willingness to let me rethink things he had decided and policies he had in place without taking it as criticism on my part of what he had done. His doing that openly got me all kinds of credibility with the organization, and quickly. “ ( Emerson Electric Company,p. 192). Persons, in turn, had this to say about Knight ( Emerson Electric Company,p. 193): “ I was sure of some basics about Chuck: that he was going to work hard, that he had good people skills, and that he was going to work with the team that was in place there. The basic transition was under control. So then I started backing off because I knew he was going to operate differently than I did in many ways. 17 And he has” “ I knew that there were going to be changes, and that he was going to accelerate the rate of acquisitions, and he has. At the same time he’s worked to expand internal growth …” “Chuck is a guy who is in a hurry. He wants to get there; he wants to build the company up,; and he has set high targets…” “ I’d also say that Emerson is 10 times more sophisticated financially today than it was when I left. Chuck has done a lot of very interesting things. He’s really creative, and he just drives his staff to be as creative as he is, and he encourages them to bring in brighter and brighter ideas.” Corporate manager James Hardymon gave his view of the relative contributions of the two leaders with the statement that , “ I really think Buck put a tremendous process in place. And I think Chuck made it more strategic.” ( p.216). Another corporate executive, Larry Keyes said that under Knight, “Emerson,developed a level of greater sophistication in the planning process. Planning became a much more meaningful vehicle in terms of driving for growth. Chuck brought many other degrees of emphasis or intensity to the process, not the least of which was his own style, which was very combative. The division officers had better be ready to defend anything and everything that was part of (the planning) conference. So the planning process became more intense, more combative, more challenging to make sure that every single facet of an important issue had bee dissected, argued and discussed.” ( Emerson Electric Company, p216). A division executive, Jan Ver Hagen, added. “ Sure you have to get used to be challenged by Chuck. That’s part of it. But the nice thing about Chuck is that it’s not personal. (Y)ou’ll see him later in the evening after dinner, and he’ll put his arm around you, and it all over with. You made your point. You had a good conference.” ( Emerson Electric Company, p.217). Finally, Knight’s successor, David Farr said, “ Six months after I succeeded Chuck Knight as Emerson’s CEO in October 2000, we faced a significant issue we had not expected: with a sudden and sharp drop in revenues, we had to announce the end of our forty-three year streak of annual increases in earnings and earnings per share…Yet the end of the earnings streak really had no impact on how the company is organized and managed…The engrained management process that had sustained our consistent earnings 18 performance for so long proved just as valuable in giving us the tools to manage in extraordinary economic time.” ( Knight, 2005, p. 221). III. REFERENCES Emerson Electric Compan. A Century of Manufacturing: 1890-1990. Emerson Electric Company. St. Louis, 1989 Knight, Charles F. with Davis Dyer. Performance without Compromise. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. 2005 Loeb, Marshall, “ Executive View: A Guide to Taking Charge,” Time, February 25,1980. 19