Technical Advice Note: Assessment of Noise

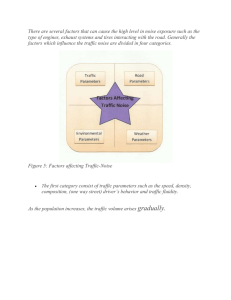

advertisement