ELTR 130 (Operational Amplifiers 1)

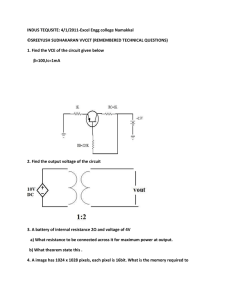

advertisement