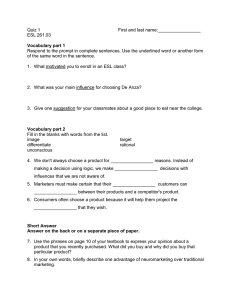

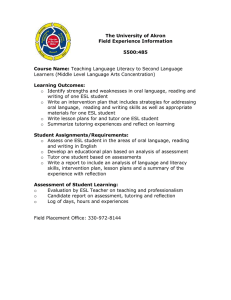

English as a Second Language Learners

advertisement