1 ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND

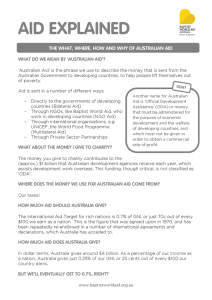

advertisement