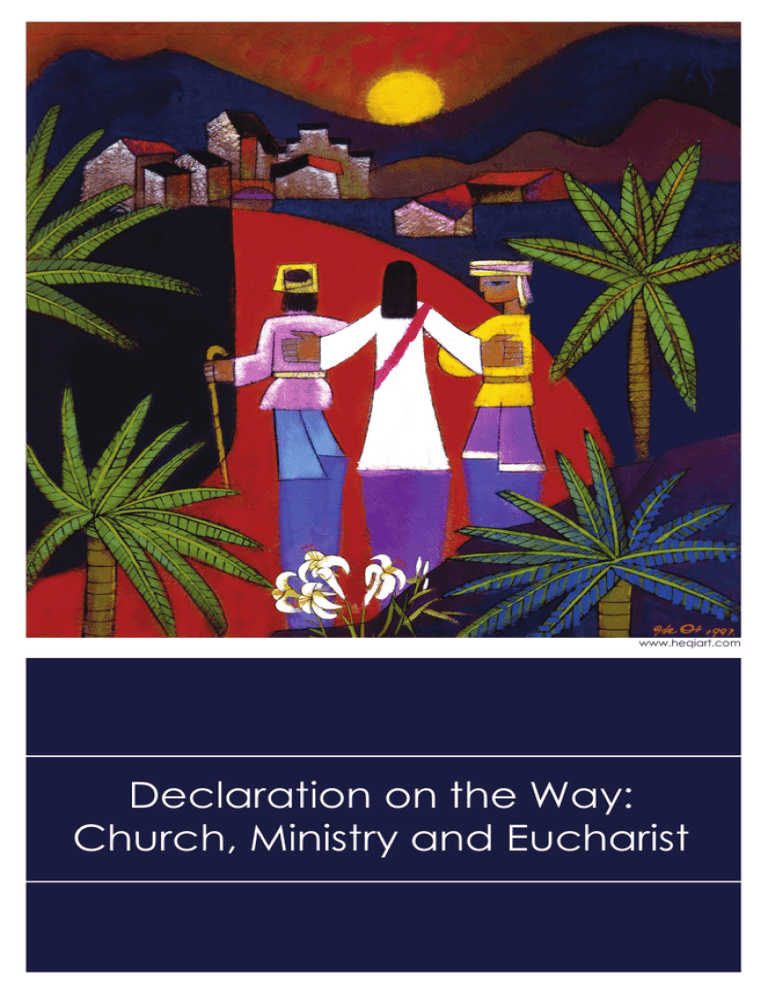

Declaration on the Way - United States Conference of Catholic

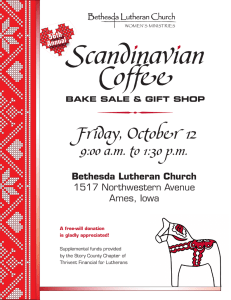

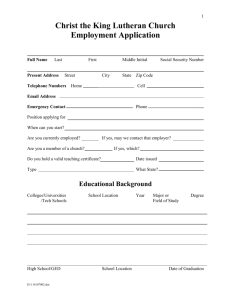

advertisement