journal of the american historical print collectors society

volume 38, number 2 • autumn 2013

THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL PRINT COLLECTORS SOCIETY

The American Historical Print Collectors Society, founded

in , is incorporated as a non-profit association in the

State of Connecticut and has been granted tax-exempt status

by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. The purpose of the

Society is:

To foster the collection, preservation, study, and exhibition

of original historical American prints that are one hundred

or more years old;

To support and encourage research and development of

publications helpful to the appreciation and conservation

of such historical prints;

To cooperate with historical societies, museums, and other

institutions and organizations having similar interests.

IMPRINT is published twice-yearly to serve these ends

and is available only through membership in the AHPCS.

Membership, now nationwide, is open to all interested

individuals and institutions. The current annual dues of

$. includes a subscription to IMPRINT, a News Letter

published four times a year, regional meetings, an invitation to the annual meeting held in a different city each

year, and the fellowship of other print collectors and

experts. We are grateful to those who join in the following

categories: Contributing, $; Patron, $; Benefactor,

$. Any amount over $ is federally tax-deductible. To

join write to: Membership Office, American Historical

Print Collectors Society, 94 Marine Street, Farmingdale,

NY 11735-5605. Our web site, www.ahpcs.org, includes

an annotated bibliography of past IMPRINT articles and

information on ordering back issues.

This issue of Imprint is supported in part by a generous bequest from Wendy Shadwell

to the American Historical Print Collectors Society.

OFFICERS AND BOARD OF DIRECTORS

PUBLICATION COMMITTEE

Robert K. Newman

James S. Brust

James E. Schiele

Lauren B. Hewes

David G. Wright

President

1st Vice President

2nd Vice President

Secretary

Treasurer

Georgia B. Barnhill

Nancy Finlay

Sally Pierce

Marshall R. Berkoff

Allen W. Bernard

Robert M. Bolton

Donald J. Bruckner

Marilyn Bruschi

Michael Buehler

Nancy Finlay

Roger Genser

Christropher W. Lane

Jackie Penny

Sally Pierce

Sue Rainey

Rosemarie Tovell

Charles Walker

John M. Zak

©The American Historical Print Collectors Society, . All rights

reserved. IMPRINT (ISSN -) is published twice a year,

Spring and Autumn, by the American Historical Print Collectors

Society, Inc., 94 Marine Street, Farmingdale, NY 11735-5605, and

is available only through membership in the Society. Reproduction

in whole or part of any article is prohibited. A list of back issues

appears on our web site (www.ahpcs.org). IMPRINT will consider

but assumes no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts.

Manuscripts should conform to the IMPRINT style, and authors may

obtain a style sheet from the editor before submitting a manuscript.

Length ranges from , to , words, with to illustrations.

Contributors are responsible for obtaining from publishers, authors,

institutions, and private owners of works of art written permission to

Sue Rainey

David G. Wright

IMPRINT

Sally Pierce

Rosemarie Tovell

Editor

Book Review Editor

REGIONAL REPRESENTATIVES

Nancy Finlay, Chair

Marshall R. Berkoff

Phyllis Brown

James S. Brust

Elisabeth Burdon

Thomas Corcoran

Kathleen Manning

Hartford, Connecticut

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Dana, North Carolina

San Pedro, California

Portland, Oregon

Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin

San Francisco, California

publish all illustrations and long text quotations taken from published

sources protected by copyright. Authors who submit manuscripts

must disclose whether the manuscript has been or will be submitted

elsewhere. All inquiries should be addressed to the editor at the above

address. IMPRINT articles are abstracted and indexed in R.I.I.A.

(International Repertory of the Literature of Art) through , and

from – in Bibliography of the History of Art and Historical

Abstracts and/or America: History and Life. The latter two databases

are also searchable on-line via EBSCOhost.

Call for Entries 2013–2014

The Ewell L. Newman Book Award

T

o recognize and encourage outstanding publications

enhancing appreciation of American prints at least

one hundred years old, the award consists of a framed citation and one thousand dollars.

Small and large works, those of narrow scope and those with

broad general coverage are equally considered. Original

research, fresh assessments, and the fluent synthesis of

known material will all be taken into account. The emphasis

is on quality and on making an outstanding contribution to

the subject. Exhibition catalogs, monographs, articles, and

works based on local sources are eligible.

Publications remain eligible for a period of roughly two years

after they first appear. Once a work has been passed on by the

Jury, it will not be considered again except in a substantially

revised edition. Jurors are collectors, authors, and scholars of

American historical prints. They are Thomas Bruhn (chair),

Storrs, Connecticut; Jonathan Flaccus, Putney, Vermont;

Ned McCabe, Peabody, Massachusetts; Sally Pierce,

Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts; and Lauren Hewes,

Shrewsbury, Massachusetts.

The most recent award, presented at the Society’s annual

conference in May 2013, honors Philadelphia on Stone:

Commercial Lithography in Philadelphia, 1828-1878, edited

by Erika Piola. Contributing authors are Jennifer

Ambrose, Donald C. Cresswell, Sara W. Duke,

Christopher W. Lane, Erika Piola, Michael Twyman, Dell

Upton, and Sarah J. Weatherwax. Philadelphia on Stone is

published by the Pennsylvania State University Press in

association with The Library Company of Philadelphia.

A chronicle of all the past Newman Award winners appears

on the Society’s web site at:

www.ahpcs.org/NEWMAN_award_winners.htm

To submit a book to the Jury for consideration, please mail to:

Thomas P. Bruhn

42 Summit Road

Storrs, CT 06268

For additional information, contact the Jury chairman at:

thomas.bruhn@uconn.edu

journal of the american historical print collectors society

volume 38, number 2

autumn 2013

Imprint

contents

2

Audubon and Cincinnati

Robert C. Vitz

18

Monkeys, Misrule, and the Birth of an American Identity in Picture Books of

the Rising Republic

Laura Wasowicz

32

William Hind Prints of the Labrador Peninsula

Gilbert L. Gignac

49

Book Reviews

Rosemarie Tovell, Book Review Editor

Catharina Slautterback, Chromo-Mania!: The Art of Chromolithography in Boston,

1840-1910; Donald C. O’Brien, The Engraving Trade in Early Cincinnati, With a Brief

Account of the Beginning of the Lithographic Trade; [ Joseph J. Felcone], Portrait of

Place: Paintings, Drawings, and Prints of New Jersey, 1761-1898, from the Collection

of Joseph J. Felcone

It is a pleasure to publish in this issue articles resulting from two talks delivered at AHPCS annual

meetings: Gilbert Gignac spoke on William Hind at the 2006 meeting in Ottawa, and Robert

Vitz spoke on Audubon in Cincinnati last May. ¶ The issue opens with Vitz’s delightful

account of John J. Audubon’s early days in America when he tried various ways to support himself and his wife Lucy, while always pursuing his passion for birds. It was in Cincinnati that

Audubon formed the determination to systematically paint as many American birds as he could

and to publish a great ornithological work. ¶ Laura Wasowicz pursues the theme of monkeys as

central characters in American children’s books. The popularity of the subject was inspired by the

publication of natural histories of exotic lands that featured monkeys and apes. Selecting examples from 1798 to 1859, Wasowicz shows how the simian characters act out commentaries on

human behavior. This role playing took on added resonance after the publication of Darwin’s On

the Origin of Species in1859. ¶ While Wasowicz touches briefly on issues of producing books and

their illustrations, Gilbert Gignac gives a definitive, almost step-by-step, account of the making

of a heavily-illustrated, two-volume documentary work, Henry Youle Hind’s Explorations in the

Interior of the Labrador Peninsula: The Country of the Montagnais and Naskapee Indians (London:

Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, 1863). Fortunately, many of the preliminary

sketches and finished watercolors of William Hind, the expedition artist, have survived, and pertinent production records of the Longman publishing house are preserved at the University of

Reading. Gignac’s account is suffused by his appreciation of the talent that both brothers brought

to a life-long dedication to give a true “picture” of Canada in text and image. ¶ The book reviews

are all on place-specific topics: chromolithography in Boston; the engraving and lithographic

trade in Cincinnati; and representations of New Jersey.

S a l l y P i e r c e , Editor

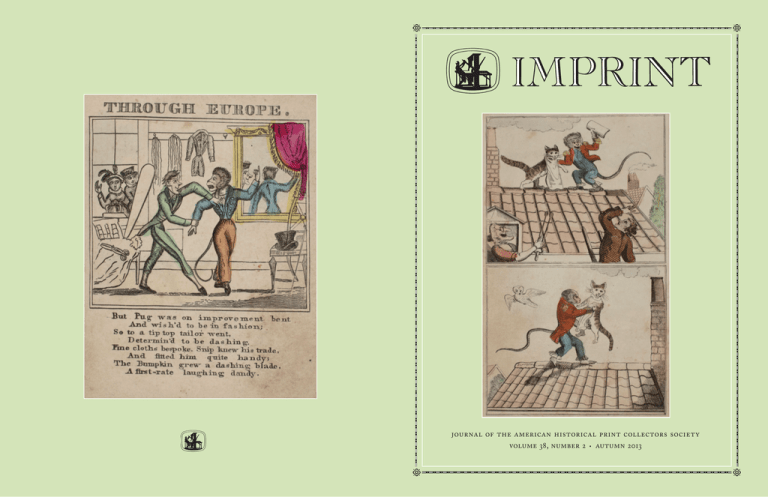

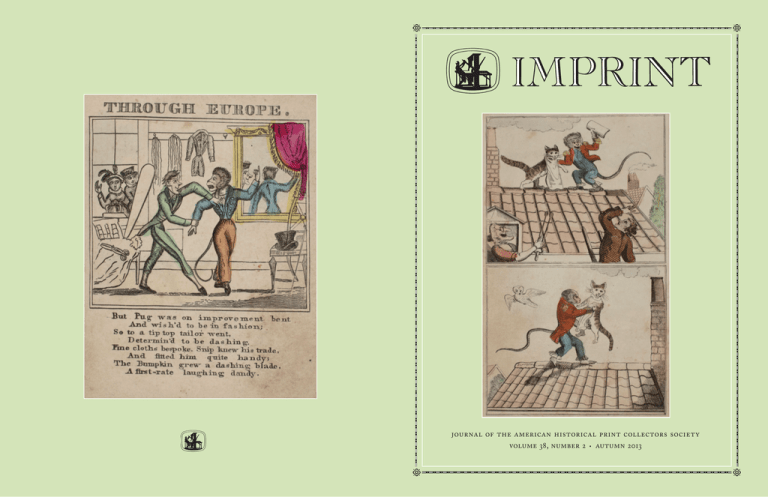

f r o n t c o v e r : Pug throws the roof tile and carries the cat to the chimney, in The Monkey’s Frolic, a Humorous

Tale (Lancaster, MA: Carter, Andrews & Co.; Boston: Carter & Hendee; Baltimore: Charles Carter, ca. 1828–1830),

leaf 4. Copper engraving, probably by Joseph Andrews, 67⁄8 x 41⁄4". Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

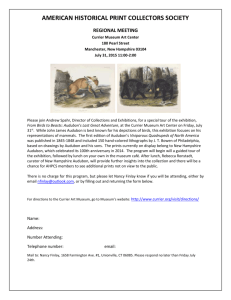

b a c k c o v e r : Pug tries on his new suit, in Pug’s Tour through Europe [Philadelphia?: Morgan & Yeager?, ca,

1824–1825?], 2. Copper engraving, probably by Hugh Anderson, 41⁄4 x 31⁄2". Courtesy of the American

Antiquarian Society.

Robert C. Vitz

Audubon and Cincinnati

ohn Audubon (fig. 1) spent only nine months in

Cincinnati, yet those months proved critical to his

career. While living here, he not only sketched six subjects for his future Birds of America, but the failure of

the Western Museum, his employer, to pay him convinced

the artist-naturalist to devote his time and energy to compiling a book illustrating the birds of the United States. But

more of all that later. To understand Cincinnati’s place in

the Audubon story, we have to know something about the

man before he arrived here in early 1820.

There is considerable confusion surrounding much of

Audubon’s early life, but it was a confusion he promoted

in an effort to make himself appear more respectable.

However, modern biographers agree that he was born on

the island of Santo Domingo, in what is now Haiti, on

April 26, 1785, the illegitimate son of Jean Audubon, a

French naval officer, and his twenty-seven-year-old

French mistress. His mother died within the boy’s first

year. Given his mother’s last name, Jean Rabin spent his

early childhood on his father’s sugar plantation. At about

the age of eight, and shortly before the revolution that

swept across the island, young Jean and his father sailed to

Nantes on the west coast of France. Here, on his father’s

considerable estate, his obliging stepmother reared him;

and his name, to obscure his illegitimacy, was changed to

Jean-Jacques Fougère Audubon. For the next ten years he

learned the ways of a French gentleman, and he excelled

at singing, dancing, shooting, riding, fencing, and playing

J

the flute and violin. He also learned to draw, and he developed a keen interest in his natural surroundings. Excitable,

enthusiastic, and considered quite handsome, he drew

people to him.

Partly to avoid service in Napoleon’s navy, Audubon’s

father sent him in 1803 to the United States where he

owned 284 acres along the fast-flowing Perkiomen Creek,

near where it joined the Schuylkill River, north of

Philadelphia. Mill Grove, with its large two-story fieldstone

house, surrounded by fertile farmland and inviting woods,

became the eighteen-year-old Audubon’s introduction to

America. “Hunting, fishing, drawing, and music occupied

my every moment,” he later wrote in his journal, “cares I

knew not, and cared naught about them.” In short order, he

established a reputation for shooting, hunting, fancy

clothes, dancing, and skating. He also soon met his neighbor’s oldest daughter, the almost seventeen-year-old Lucy

Bakewell (fig. 2). This intelligent, well-read, musical young

woman found Audubon fascinating, and her steadfast character served as an important counterweight to his romantic

exuberance. She, too, enjoyed riding and dancing, shared his

disdain of city life, and helped him learn English. Of course,

despite his somewhat flamboyant social life, Audubon also

began his serious observation of the natural world, often

joined by Lucy, and he experimented with drawing life-like

images of the birds he shot.

Four years later, and after an unsuccessful business adventure, the couple married. The day following the brief cere-

r ob e rt c . v i t z grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio, received his B.A. from

DePauw University, his M.A. from Miami University, and his Ph.D. from

the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. For thirty-six years he

taught United States history at Northern Kentucky University in

Highland Heights, Kentucky, before retiring in 2008. His principal

research interests are American cultural and intellectual history, with a

particular emphasis on the contributions of nineteenth-century

Cincinnati. He has published in a variety of scholarly journals including

New York History, Queen City Heritage, American Music, and the Filson

Club History Quarterly. He is the author of The Queen and the Arts:

Cultural Life in Nineteenth-Century Cincinnati (Kent, OH: Kent State

University Press, 1989), and At the Center: 175 Years at Cincinnati’s

Mercantile Library (Cincinnati: Mercantile Library Association, 2010).

f ig . 1 , op p o s i t e . Engraved by Charles Turner after a painting by

Frederick Cruikshank, John J. Audubon, painted in London ca.1831.

Engraving, 91⁄2 x 7" (plate), published by Robert Havell, London, 1835.

Boston Athenaeum

2

vitz

•

au d u b on a n d c i n c i n n at i

3

4

Imprint

f ig . 2 . Photograph of a miniature by Frederick Cruikshank, Lucy

Bakewell Audubon, painted in London ca. 1831. Collection of the NewYork Historical Society. Negative #44214.

mony in the Bakewell parlor, they departed for Louisville,

Kentucky, where Audubon and Ferdinand Rozier, a partner, hoped to launch successful business careers. They traveled by stage across Pennsylvania, ferrying across the

numerous rivers and ascending mountain ridges on the

rutted and often muddy roads. At Pittsburgh they waited

for their furniture and household goods to catch up with

them. And then it was down the Ohio River by cumbersome flatboat, a five hundred-mile journey that deposited

them in Louisville in a remarkable ten days. That summer

Audubon divided his time between establishing customers

for his store and wandering along the river in pursuit of

birds. Evenings were spent socializing.

The Louisville years provided some unexpected benefits

for Audubon, particularly the arrival of Alexander Wilson

in 1810. The Scottish-born naturalist, already considered

America’s leading ornithologist, visited Louisville in search

of subscribers for his great multi-volume work, American

Ornithology, then in the process of being published.

Although tempted to subscribe, Audubon declined. He

•

autumn 2013

also came to the realization that his own illustrations were

superior to Wilson’s and that he knew more about bird

behavior and habitat. However, the two men did spend

several days birding together, before Wilson started back

east. He died three years later, leaving his final volume to

be completed by a friend.

If Louisville offered good company, it did not provide

much business success, and after two years the partners,

along with Lucy and the newly-born Victor Gifford

Audubon, set out for Henderson, Kentucky, a small village

some 125 miles downstream from Louisville. Located on

the edge of the frontier and in a thinly-populated region,

one wonders why Audubon thought commercial success

would find them there. It didn’t. But, there were always new

birds. While Rozier tended to the store, Audubon often

went wandering, sometimes for weeks at a time. He sighted a large flock of white pelicans, managed to misidentify

sandhill cranes, and took great delight in spotting scarlet

tanagers, ivory-billed woodpeckers, and other forest birds.

Audubon’s rendering of the Ivory-bill (fig. 3) (probably

extinct, despite several reported recent sightings) remains

one of his most popular bird portraits. On one of his wilderness rambles, Audubon stared in awe as millions of passenger pigeons migrated overhead. “The air was literally filled

with pigeons,” he noted in his ever present journal, “the

light of noon day was obscured as by an eclipse; the dung

fell in spots not unlike flakes of melting snow; and the continued buzz of wings had a tendency to lull my senses to

repose.” One hopes that he, at least, wore a hat. Of course,

the passenger pigeon (fig. 4) is now also extinct. The last of

the species—named “Martha” in honor of Martha

Washington—died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. Her

body is in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution.

By this time Audubon had refined his drawing technique. Using a board marked with a wire grid, he would

secure a freshly killed bird to it in a lifelike manner by

means of additional wires and threads. He then sketched

the bird on drawing paper marked with an identical grid,

so that the result was an image both lifelike and life-size.

Background and foliage could be added later.

As their store foundered, Audubon and Rozier invested

in two other projects, a large saw and grist mill and, later, a

small steamboat. Both proved unsuccessful. Audubon has

often been accused of being a poor businessman, and there

f ig . 3 , op p o s i t e . John James Audubon, Ivory-billed Woodpecker, ca.

1826. Study for Havell plate no. 66, inscribed: “Drawn from Nature by

John J. Audubon/ Louisianna [sic],” watercolor, pastel, black ink,

graphite, gouache, and white lead pigment on paper, 381⁄4 x 251⁄16", laid

on card. Collection of the New-York Historical Society. Digital image

created by Oppenheimer Editions. Object #1863.17.66.

vitz

•

au d u b on a n d c i n c i n n at i

5

6

Imprint

•

autumn 2013

vitz

•

au d u b on a n d c i n c i n n at i

7

f ig . 5 . Drawn and engraved by Doolittle & Munson. Cincinnati, ca.

1831. Engraved vignette, 5 x 9", from a map. Courtesy of the Cincinnati

Museum Center.

is considerable truth to that, but it was the financial Panic

of 1819 that finally did him in. The nation’s first depression

dried up credit and brought on a severe contraction of the

economy. In July of that year Audubon filed for bankruptcy. Court records listed his possessions: one piano, 150

books, 20 Windsor chairs, various rugs and carpets, Lucy’s

wedding silver, 4 mirrors, china, 1 large walnut desk, 4 silver candlesticks, 1 fiddle, 1 flageolet, a flute, a guitar, several beds and cribs, and livestock, plus drawing materials, and,

of course, a large portfolio of drawings. The estimated value

was $7,000, which was used to offset his debts. Fortunately

for posterity, a friend purchased the drawings and drawing

f ig . 4 , op p o s i t e . John James Audubon, Passenger Pigeon, 1824.

Study for Havell plate no. 62, inscribed: “Drawn from Nature/

Pittsburgh. Pena./ J.J. Audubon,” watercolor, pastel, graphite, gouache,

black chalk, and black ink on paper, 26 5⁄16 x 181⁄2", laid on card.

Collection of the New-York Historical Society. Digital image created by

Oppenheimer Editions. Object #1863.17.62

materials and returned them to Audubon. At this point, no

doubt the lowest point in his life, fortune turned.

Cincinnati’s Western Museum offered him a position.

Cincinnati (fig. 5), founded in 1788, was a thriving city of

about 10,000 people in 1820, and already the largest community in the western country. Dr. Daniel Drake (fig. 6),

the city’s preeminent physician, scientist, town promoter,

and civic organizer, had been the driving force in establishing a scientific institution known as the Western Museum.

As one of the museum’s five managers, he sought to fill it

with “the natural productions and antiquities of the

Western Country….” The Reverend Elijah Slack, another

manager and also the president of the recently opened

Cincinnati College, agreed to house the museum’s collection in the college rooms. First, however, they needed to

recruit a staff. Largely on the strength of a letter from

Robert Todd of Lexington, Kentucky, (the father of Mary

Todd Lincoln), Drake hired Audubon as a taxidermist “to

stuff birds and fishes.” A very confident Drake offered a

handsome salary of $125 per month. To make the situation

8

Imprint

•

autumn 2013

f ig . 6 . Engraved by A. H. Ritchie, Daniel Drake, M.D., age 65.

Published by Robert Clarke & Co., Cincinnati, for the Ohio Valley

Historical Series, no. 6, 1870. Engraving, 113⁄8 x 7 1⁄2". Courtesy of the

Cincinnati Museum Center.

f ig . 7. Alonzo Chappel, probably influenced by a painting by John

Woodhouse Audubon, John J. Audubon. Hand-colored steel engraving,

7 1⁄4 x 51⁄4" (image), published by Johnson , Fry & Co., New York, 1861.

Courtesy of the Old Print Shop.

even more attractive to Audubon, the college owned a copy

of Alexander Wilson’s American Ornithology. The thirtyfive-year-old Audubon accepted immediately. John

Audubon is often depicted in his later portraits as a rustic

frontiersman (fig. 7), a sort of companion to James

Fennimore Cooper’s literary character, Natty Bumppo.

This was a pose the artist skillfully used to market himself

in England, much in the way Benjamin Franklin had done

in France a half-century earlier. However, in all likelihood,

while in Cincinnati, he looked more like the gentlemanly

self-portrait painted in oils in 1822 or 1823 at Beech

Woods, Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. Audubon painted

himself wearing a green jacket, white waistcoat, white shirt

with starched, pointed collar, and necktie tied in a bow. His

curly brown hair is brushed up from his forehead and falls

just to the top of his collar.1

Whatever his looks, by January 1820, the Audubons

were in Cincinnati. While Lucy set up housekeeping in a

small, cheaply furnished rented house on East Third

Street, John worked closely with Robert Best, the Western

Museum’s curator, who showed him many of the best bird

watching spots in the area. It was Best who informed him

about a “strange species” of bird in Newport, Kentucky, a

bird that built its nests in clusters attached to the walls of

f ig . 8 , op p o s i t e . John James Audubon, Cliff Swallow, 1820. Study

for Havell plate no. 68, inscribed: “Cincinnati Ohio May 20th 1820/

John J. Audubon,” watercolor, pastel, black and brown ink, and graphite

with touches of gouache on two sheets of paper, 1813⁄16 x 117⁄8", laid on

card. Collection of the New-York Historical Society. Digital image created by Oppenheimer Editions. Object #1863.17.68.

vitz

•

au d u b on a n d c i n c i n n at i

9

10

Imprint

the military post there. Off went Audubon to observe and

sketch these cliff swallows (fig. 8). Best also placed an

advertisement in a local newspaper, asking people to bring

in specimens for mounting. Although Best meant dead

specimens, one morning Audubon was surprised by a

woman who brought in a large live bird, pinned in her

apron, which had fallen down her chimney the night

before. Recognizing it as a juvenile least bittern (fig. 9), he

sketched it while it stood motionless on his table. His

curiosity also led him to perform an experiment with two

upright books, set one inch apart, to see if the bird could

squeeze through without the books falling. It did. This

indicated to him how bitterns could easily move through

reeds without being noticed.

During those Cincinnati months, Audubon also made

drawings of a sharp-shinned hawk and a cedar bird, now

f ig . 9 . John James Audubon, Least Bittern, 1820, 1832. Study for

Havell plate no. 210, inscribed: “No. 1- a small Bittern.” Watercolor,

graphite, pastel, collage, gouache, and black ink on paper, 143⁄4 x

2111⁄16", laid on card. Collection of the New-York Historical Society.

Digital image created by Oppenheimer Editions. Object #1863.17.210.

•

autumn 2013

called a cedar waxwing. Both of these images found their

way into his Birds of America. A fifth bird proved the most

exciting for Audubon, for he had never seen this one

before. Indeed, imagining it to be a newly discovered

species, he labeled it the “Cincinnati Gull” (fig. 10). In his

journal, he described this first encounter: “They would

alight side by side, as if intent on holding a conversation….

We watched them for nearly a half an hour, and having

learned something of their manners, shot one, which happened to be a female. On her dropping, her mate almost

immediately alighted beside her, and was shot.” Well, so

much for avian chivalry. Later, he learned that the bird had

already been named for Charles Lucien Bonaparte,

Napoleon’s nephew and an accomplished ornithologist in

his own right, and so it is known today as Bonaparte’s Gull

(fig. 11). Audubon’s shooting of specimens can be disturb-

vitz

•

au d u b on a n d c i n c i n n at i

11

f ig . 1 0 . John James Audubon, Bonaparte’s Gull, originally labeled

Cincinnati Gull, 1820. Inscribed: “Drawn from Nature & from the

Living Bird/by John J. Audubon Cincinnati Ohio Augt. 19.1820.”

Pastel, graphite, watercolor, and black ink on paper, 115⁄16 x 17 3⁄16", laid

on card. Collection of the New-York Historical Society. Digital image

created by Oppenheimer Editions. Object #1863.18.26.

ing to modern sensibilities, but there was no other way for

an artist to draw a bird with any accuracy, and he seldom

killed indiscriminately. Working with dead specimens also

permitted him to open up the birds’ stomachs to determine

what food had recently been eaten, thus allowing him to

learn more about their habitat and eating habits. Often,

after sketching a bird in the field, he would cook and eat it.

Although not something the Audubon Society currently

recommends, Audubon’s notes do provide us with some

interesting tastes, albeit vicariously. Grebes, a type of duck,

proved “fishy, rancid and fat.” No surprise there. Redwinged blackbirds he considered “good and delicate.” The

hermit thrush, somewhat smaller than a robin, was “fat and

delicate,” and the greater yellowlegs, a large shorebird, was

deemed “very fat but very fishy.” The northern flicker, a

species of woodpecker that often feeds on the ground, he

found “very disagreeable,” complaining that it had “a strong

flavor of ants.” The cedar waxwing, however, received his

highest culinary praise: it is “sought by every epicure for the

table,” he wrote. Even the turkey vulture, that ever present

companion of road kill, did not escape his palate, for he

concluded that it “tasted well.”2

Audubon’s relationship with the Western Museum did

not go smoothly. The same economic crisis that had caught

him in Henderson swept through Cincinnati’s financial

community. Bank notes depreciated and land values collapsed. Daniel Drake, the civic leader and town promoter,

had to sell his home and move to a log house on the edge of

the city, which he dubbed “Mount Poverty.” The Western

Museum quickly found itself with insufficient operating

funds. As Audubon wryly noted some years later, “I found,

sadly too late, that the members of the College Museum

12

Imprint

•

autumn 2013

vitz

were splendid promisers, but poor paymasters.” In lieu of any

payment, Dr. Drake did support a public display of

Audubon’s drawings. The editor of the Inquisitor-Advertiser

praised the exhibit: “No one can examine them without the

strongest emotions of surprise and admiration,” he wrote.

“We hope that every person will avail himself of the first

opportunity to examine specimens in this branch of fine arts,

which for fidelity and correctness in execution, are so excellent as to surpass…all others that we have ever witnessed.”3

The Audubons limped along in Cincinnati, aided by

Lucy’s careful management and the city’s low cost of living.

“Our living here is extremely moderate,” John wrote, “the

markets are well supplied and cheap, beef only two and

one-half cents a pound, and I am able to provide a good

deal myself; Partridges are frequent in the streets, and I can

shoot Wild Turkeys within a mile or so; Squirrels and

Woodcocks are very abundant in the season, and fish

always easily caught.” Without pay, however, both John

and Lucy turned to other sources of income. In late

February, John Audubon opened a drawing school, advertising in the Inquisitor-Advertiser for pupils to learn drawing and the French language (fig. 12). About twenty-five

students signed up. Two months later he began teaching at

a Miss Deeds’s school for “females of all ages” (fig. 13). In

addition, Lucy taught the usual elementary subjects to private pupils at her home. For some, she even provided music

lessons. Without regular work, however, John turned to

portrait painting, the bread and butter for almost all

American artists in the first half of the nineteenth century,

charging five or ten dollars a head. Among his subjects

were Dr. Drake, the Rev. and Mrs. Elijah Slack, John

Cleves Symmes, and General and Mrs. William Lytle.

It is not clear how long Audubon remained employed by

the Western Museum. Sometime during the spring of

1820, probably in April, Drake informed him that the

museum could no longer afford his services—not that he

had received any pay yet—but it was clear to all that funding for the museum had dried up. The museum did hold an

official opening celebration in June at which Drake singled

out Audubon for his talent, mentioning that his portfolio

already included drawings of many birds not in Wilson’s

American Ornithology.

While the Audubons were scrambling to make ends

meet, the Long Expedition arrived in Cincinnati. Major

f ig . 1 1 , op p o s i t e . John James Audubon, Bonaparte’s Gull, ca. 1821,

1830. Study for Havell plate no. 324, watercolor, collage, graphite, pastel, black chalk, gouache, and black ink on paper, 211⁄4 x 153⁄16", laid on

card. All three birds were drawn separately and pasted on the background. Specimens were obtained in Ohio in 1820, while on an outing

with Robert Best, Curator of the Cincinnati Museum at that time.

Collection of the New-York Historical Society. Digital image created by

Oppenheimer Editions. Object #1863.17.324.

•

au d u b on a n d c i n c i n n at i

13

Stephen H. Long, of the Army Corps of Engineers, was on

his way west. He and his party arrived in May on the

steamboat Western Engineer, designed especially for exploring the upper reaches of the Missouri and Platte Rivers.

The boat measured 75 feet by a very narrow 13 feet. It carried several cannon, boasted a mast and a sail, and vented

waste steam from its serpent-carved prow. One presumes

that this was designed to intimidate native peoples. The

crew included Thomas Say, an entomologist, and Titian

f ig . 1 2 , a b ov e . Advertisement for a drawing school run by John J.

Audubon, from the Cincinnati Inquisitor-Advertiser, June 27, 1820.

Courtesy of the Cincinnati Museum Center.

f ig . 1 3 , b e l o w . Advertisement for Miss Deeds’ School, where

Audubon taught drawing and painting, from the Western Spy and

Cincinnati General Advertiser, March 16, 1820. Courtesy of the Cincinnati

Museum Center.

14

Imprint

Peale, artist, taxidermist, and the youngest son of artist

Charles Willson Peale. One evening, those two men spent

several hours looking with great admiration at Audubon’s

work. Their enthusiastic support provided an important

emotional boost to Audubon’s developing plans.

With apparently little future in Cincinnati, John and

Lucy made a decision—and it was very much a joint decision—to go ahead with the concept of a large book on

American birds that would be far superior to Alexander

Wilson’s work, both in number of species represented and

in their illustration. It was also a rash and romantic decision which would ultimately require Audubon to become

an artist, writer, salesman, and collections agent. But it did

provide him with a goal that he eagerly embraced. The

patient and loyal Lucy must have recognized that this was

her husband’s destiny, and, of course, hers as well. The plan

had Audubon traveling to New Orleans where he would

explore the region, draw birds, and find a way to support a

family. Lucy and the children would follow later, after John

had established himself in the Crescent City. Before

departing Cincinnati, Audubon purchased a calf-bound

book the size of a ledger, into which he would pour his

observations about the trip. This journal is now in the collection of Harvard’s Houghton Library.

Audubon traveled light. On the first day he recorded his

meager possessions: several books, two guns and tackle,

watercolors, brushes, pencils, chalk, sheets of art paper in a

tubular tin case, wire for mounting, a violin, a flute, and one

wide-brimmed hat. No doubt he also brought an extra set

of clothes, for he had promised Lucy he would change his

shirt every week. “My talents are to be my support,” he

wrote, “and my enthusiasm my guide in my difficulties.” In

exchange for free passage on a large flatboat, he agreed to

supply fresh game for the crew and the several passengers.

In addition, Audubon carried four letters of introduction,

provided by Dr. Drake, Rev. Slack, General William

Henry Harrison, and Senator Henry Clay, the latter’s

addressed to officers and agents of the federal government.

He also arranged to bring along his most gifted student,

thirteen-year-old Joseph Mason, the son of a local printer

and bookseller. Mason had displayed a particular talent for

drawing plants, and in subsequent months he would draw

the vegetation on which some of Audubon’s birds rest.

Some years later, their friendship disintegrated when

Mason learned that Audubon had left his name off many

of the plates for Birds of America.

Thus, late in the afternoon on October 12, 1820, man and

boy departed from Cincinnati’s bustling public landing. We

can assume that Lucy and the children were there to see them

off, but an air of sadness must have settled over the family

because they planned on a separation of some seven months.

That proved wildly optimistic. Fourteen very difficult months

passed before they were reunited. Lucy divided her time

•

autumn 2013

between Cincinnati and Louisville, teaching when she could.

When Audubon could, which was very irregular, he sent

money to her; and Daniel Drake eventually came up with

$400 in back pay, which either indicates that Audubon

worked for the museum less than four months or that the

museum remained unable to fulfill its financial commitment.

This became the bitterest period in Lucy Audubon’s life.

That first night on the Ohio, the flatboat floated only

eighteen miles, and in the morning Audubon and young

Mason went ashore to procure food for the day. Their hunt

produced thirty quail, one woodcock, twenty-seven gray

squirrels, a barn owl, and a juvenile turkey vulture. Still

moving with the sluggish river, the flatboat reached

Louisville and then, on November 2, Henderson, the scene

of so many sad memories. Three weeks later they stopped

in New Madrid, a shabby Missouri village almost

destroyed eight years earlier by the great earthquake that

bears its name. On January 2, they tied up at Natchez,

where Audubon hustled portraits in hopes of sending

money back to Lucy. Eight days later they arrived in New

Orleans, twelve weeks after departing Cincinnati.

Thus began the second half of Audubon’s life. He spent

several years in Louisiana, moving from New Orleans to

Bayou Sara to Natchez and back to New Orleans. Portrait

painting provided an irregular income, and when necessary

he tutored young Louisianans in painting, music, dancing,

and fencing. After Lucy and the children finally joined him

in December 1821, she also worked as a teacher and governess. But always there were birds. These years produced

some of his finest work. In 1824, he traveled to Philadelphia

to seek a publisher for his book. This proved unsuccessful,

and two years later he left for Great Britain and future fame.

In London, Audubon made his fortunate and life-changing

connection with Robert Havell Jr. and began the process of

turning his remarkable portfolio of drawings into the 435

hand-colored engravings that we are so familiar with today.

For the next twelve years he traveled between the United

States and England. Indeed, during that time, he made

eight Atlantic crossings. In Great Britain, he visited not

only London, but Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, and

Edinburgh, in attempts to find subscribers for his work in

progress. He also managed to visit France on two occasions,

where he gained public recognition but few subscriptions.

During these years, Lucy twice joined him in England, but

for most of this period they were separated, and her letters

reflect the strains on their marriage. When Audubon was in

the United States, he also sought out potential purchasers of

f i g . 1 4 , o p p o s i t e . Broadside advertisement for the Western

Museum, ca. 1825–1850. Wood engraving, 13 x 6" (sheet). Courtesy of

the Cincinnati Museum Center.

vitz

•

au d u b on a n d c i n c i n n at i

15

16

Imprint

his book, at approximately a thousand dollars a set. But all

the time, he never stopped drawing. Between 1829 and

1837, he visited upstate New York, Nova Scotia and

Labrador, the newly established Republic of Texas, South

Carolina, and much of Florida, including Key West and the

Dry Tortugas. It would be hard to find another American

who had visited as much of the United States as Audubon.

With the publication of the great double elephant folio

edition of Birds of America, Audubon secured his reputation.

He went on to produce the companion five-volume

Ornithological Biography, which provided the descriptive text

for Birds of America, and later he produced another multivolume production on the Viviparous Quadrupeds of North

America, along with several other works. He was accepted as

a fellow in the Royal Society and the Linnean Society of

London, as well as the French Academy of Sciences, and

spent his last years living comfortably in a house overlooking

the Hudson River, north of New York City.

But, we are not quite finished with his Cincinnati connection. On two later occasions Audubon stopped in

Cincinnati while traveling from Pittsburgh to Louisville.

In November 1829, although he was unable to see Dr.

Drake, he did stop by the Western Museum. “It scarcely

improves since my last visit,” he wrote to a friend in

Philadelphia, “except indeed by wax figures and such other

shows as are best suited to make money and the least so to

improve the mind.” The Western Museum had indeed fallen on hard times. Sold by the original managers, it had

now become a museum of entertainment, for which wax

figures and its so-called “Infernal Regions” (fig. 14) proved

highly popular—more popular apparently than stuffed

birds and fish. Fourteen years later, Audubon again stopped

briefly in the city, arriving at three o’clock in the morning

and departing eight hours later. There is no record that he

even left the boat.

In the 1870s and 1880s, Cincinnati could boast of having two complete sets of The Birds of America. In 1870 the

Cincinnati Public Library acquired its copy, which had

been originally purchased by a Dr. Thomas Edmondson, a

wealthy physician and patron of the arts in Baltimore.

Several years after Edmondson’s death, his library was sold

at auction in 1870. The four-volume Birds of America and

the companion five-volume Ornithological Biography

together fetched $750. It is presumed that the buyer was

•

autumn 2013

Joseph Longworth of Cincinnati, the son of Nicholas

Longworth, for it was he who sold the Birds to the library

for $1,000. It now rests in a handsome case in the

Cincinnati Room on the library’s third floor. The other set

belonged to Henry Probasco, one of Cincinnati’s wealthiest citizens during the nineteenth century, and the donor of

the magnificent fountain that sits at the corner of Fifth and

Vine streets. Probasco, who made his fortune as a partner

in a wholesale hardware company, acquired an extensive

library after he retired in 1856. Along with early English

Bibles, several rare editions of the First, Second, and

Fourth Folios of Shakespeare, a 1497 copy of Dante’s

Divine Comedy, and scores of other wonderful books,

Probasco had purchased his Audubon. Its provenance is

unknown. Unfortunately, his library did not remain in the

city. After enjoying a lavish life-style, Probasco found it

necessary to sell his collection in 1890, and it went to the

recently-founded Newberry Library in Chicago. However,

the Newberry did not keep the Audubon set. As a result of

an agreement among the Chicago Public Library, the

Newberry, and the John Crerar Library, The Birds of

America went to the latter in 1897. It is now housed at the

University of Chicago.

And finally, there is the case of what might have been. In

the 1840s the board of the Mercantile Library—the venerable 178-year-old institution in which this talk was presented—discussed the purchase of an Audubon. This

probably was the double elephant folio edition. However,

by the time a decision was reached, the set was no longer

available. In late 1859 the Mercantile Library board again

entertained the idea of purchasing an Audubon. I believe

this to have been the rare Bien edition, but, since it was

being released in installments, the board chose to wait for

the completion of the set. Then the Civil War came, and

no more is heard of Audubon in the minutes of the

Mercantile Library board meetings.

In addition to works by the artist now housed in

Cincinnati collections, a three-dimensional monument to

John Audubon’s time in the area can be visited. Directly

across the river from Cincinnati, in the Riverside area of

Covington, Kentucky, a bronze statue stands. Audubon is

looking out over the Licking River, with sketchbook in

hand. You are welcome to ask him any questions—but he

is not much of a conversationalist.

vitz

notes

This article is developed from the talk presented at the

AHPCS annual meeting in Cincinnati in May 2013.

1. Audubon’s self-portrait painted at Beech Woods, is reproduced as the

frontispiece to Audubon’s America: The Narratives and Experience of

John James Audubon, edited by Donald C. Peattie (Boston: Houghton

Mifflin Co.; The Riverside Press, Cambridge, 1940). The self-portrait can also be viewed in Home to Roost: Ornithological Collections at

Lehigh University, a web exhibition on the Lehigh University Library

Services site (http://www.lehigh.edu/).

2. Regarding Audubon’s avian eating preferences, five of the references

come from Durant and Harwood, p. 122. Reference to the taste of

flicker and cedar waxwing come from Olson, pages 158 and 122

respectively.

3. Cincinnati Inquisitor-Advertiser, February 29, 1820, p. 3.

•

au d u b on a n d c i n c i n n at i

17

bibliography

Adams, Alexander B. John James Audubon: a Biography.

New York, 1966.

Audubon, John James. The Audubon Reader. Edited by

Richard Rhodes. New York, 2006.

________. Ornithological Biography, or An Account of the

Habits of Birds of the United States of America, Accompanied

by Descriptions of the Objects Represented in the Work

Entitled “The Birds of America,” and Interspersed with

Delineations of American Scenery and Manners. 5 vols.

Edinburgh: A. Black, 1831-1849.

Brenner, Barbara. On the Frontier with Mr. Audubon. New

York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1977.

Durant, Mary B, and Michael Harwood. On the Road with

John James Audubon. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1980.

Ford, Alice. John James Audubon. New York: Abbeyville

Press, 1988.

Gillespie, Dorothy. John James Audubon: Relations of the

Naturalist with the Western Museum at Cincinnati.

[Cincinnati?]: Cincinnati Society of Natural History,

[1937].

Harris, Edward. Up the Missouri with Audubon: the Journal

of Edward Harris. Edited and annotated by John

Francis McDermott. Norman: University of Oklahoma

Press, 1951.

Herrick, Francis H. Audubon, the Naturalist: a History of His

Life and Times. New York: Appleton-Century, 1938.

Keating, L. Clark. Audubon: the Kentucky Years. Lexington:

University Press of Kentucky, 1976.

Olson, Roberta J. M. Audubon’s Aviary: the Original

Watercolors for “The Birds of America”. New York: NewYork Historical Society, 2012.

Rhodes, Richard. John James Audubon: The Making of an

American. New York: Knopf, 2004.

Vedder, Lee. John James Audubon and the “Birds of America:”

A Visionary Achievement in Ornithological Illustration.

San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 2006.

Laura Wasowicz

Monkeys, Misrule, and the Birth of

an American Identity

in Picture Books of the Rising Republic

M

onkeys became playful fixtures in American picture books issued between 1790 and 1860. They

populate nearly forty American children’s books

published in that seventy-year span, long before Curious

George popped onto the scene.1 This debut of the picture

book monkey reflects the publication of natural histories in

the late eighteenth century that featured monkeys. The

influential writer Oliver Goldmith’s History of the Earth and

Animated Nature had an extensive chapter on monkeys, and

his text was quickly adapted for the use of schools by Mary

Pilkington, thus increasing access to information about

monkeys and their habitat for both adults and children.2

Monkeys were teeming inhabitants of exotic hinterlands in

the Old and New Worlds. These newly discovered creatures

quickly became fashionable inhabitants of children’s books

as well, both as mischievous pets and eventually as freewheeling proto-human agents.

In children’s books, these free-agent monkeys are clearly

distinguished from dogs, donkeys, pigs, and other animals

trained as learned animals by humans. A learned animal

constantly under the master’s control is quite different

from a willful, untrained monkey. Cultural scholar Brett

Mizelle observes, “The blurring of boundaries between

humans and animals helps to account for the tremendous

popularity of performances of ‘learned pigs,’ which

amazed and amused audiences by spelling, solving mathematical problems, and answering questions by picking up

cards placed upon the floor. In the late eighteenth century the learned pig proved a sensation in London.”3 One

l au ra was o w ic z is Curator of Children’s Literature at the American

Antiquarian Society. For the past twenty-six years, she has worked to

acquire, catalog, and provide reference service for the AAS collection of

twenty-four thousand children’s books issued between 1650 and 1899.

She has written articles on various aspects of nineteenth-century

American children’s book publishing, picture book iconography, and child

reading habits. She is also the editor of the Nineteenth-Century American

Children’s Book Trade Directory, available on the AAS website

(http://www.americanantiquarian.org). Wasowicz holds a master’s degree

in Library Science from the University of Chicago, a master’s degree in

History from Clark University, and a bachelor’s degree in History from

Rockford College.

18

fine example of a learned dog is found in the early nineteenth-century picture book Peter Pry’s Puppet Show. Part

the II.4 The illustrations depict a variety show of curiosities, including a copper-plate image of two small children

watching a trained dog pick out letter cards under the

watchful eye of its master (fig. 1). The dog wears no

clothes and is clearly controlled by the master. The verse

text reinforces the importance of literacy to its young readers: “A learned Dog you now behold/ Much more so than

his betters./ Do you by him example take,/ And study well

your Letters.”5 The children in the scene look as though

they are curiously taking in the dog’s “wisdom.”

f ig . 1 . A learned dog and his master, in Peter Pry’s Puppet Show. Part

the II (Philadelphia: Morgan & Sons, ca. 1821–1834), 7. Copper

engraving, probably by William Charles, 5 x 41⁄16" (plate). Courtesy of

the American Antiquarian Society.

wa s o w i c z

•

m 0 n k e y s i n p ic t u r e s b o ok s

19

f ig . 2 . Norwegian Man/Orangutan, in People of All Nations: An Useful

Toy for Girl or Boy (Albany: Henry Collins Southwick, ca. 1812), 30–31.

Wood engraving by an unknown artist, two adjacent pages each measuring 23⁄4 x 27⁄8 ". Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

Unlike the domestic animal, the monkey emerges into

early nineteenth-century children’s picture books as a free

agent, frequently occupying the liminal space between

human and animal. This ambiguity is marvelously captured in People of All Nations: An Useful Toy for Girl or Boy

(fig. 2). Children’s books depicting various ethnic groups

in native costume were highly popular throughout the

nineteenth century. This is a fairly early example in miniature format. In People of All Nations, the ethnic groups are

arranged alphabetically, providing young readers with a

secular counterpart to the religiously inspired alphabet

found in The New England Primer, a universally recognized source of alphabet instruction at the time. Alphabet

books have been recently rediscovered by researchers as

rich repositories of culturally recognized racial and ethnic

stereotypes, and indeed provide rich fodder. In this case, a

neatly dressed Norwegian man appears as the opposite (in

more ways than one) to the orangutan. The description for

the latter is quite interesting: “An Ourang-Outang is a

wild man of the woods in the East Indies. He sleeps under

trees, and builds himself a hut; he cannot speak, but when

the natives make a fire in the woods, he will come to warm

himself.”6 The wood-engraved illustration and this short

passage reflect how fluid popular attitudes were toward

the distinction between human and animal. The orangutan (which we now consider to be an animal) is classed

with other humans, and called “a wild man” in the description. At the same time, there was debate in the AngloAmerican world about the degree to which African slaves

and other indigenous people were truly human. For this

reason, this image of the orangutan provides an important

clue to our modern understanding of cultural attitudes

toward race, ethnicity, and ultimately, humanity in the

early American republic.

Richard Johnson’s The History of a Doll contains one of

the earliest monkey characters in an Anglo-American

children’s story.7 Johnson wrote a number of titles for the

English pioneer children’s book publisher John Newbery.

20

Imprint

f ig . 3 . The wily pet monkey grasps the ill-fated doll, in Richard

Johnson, The History of a Doll (Boston: John W. Folsom, 1798), 25.

Wood engraving by an unknown artist, 37⁄8 x 2 1⁄2". Courtesy of the

American Antiquarian Society.

He wrote History of a Doll in 1780, and it was first issued

in the United States by the Boston publisher John W.

Folsom in 1798. The doll’s fate is ultimately at the mercy

of a wily monkey that is definitely a creature of the New

World. The story chronicles the adventures and substantial tribulations of a doll. It is nearly destroyed by her first

mistress’ brother, and later by a sailor while en route to the

West Indies with its second mistress. But her trials are not

over; the master of the house kept a “mischievous monkey,” which seizes it while the doll’s mistress sees to company at the door (fig. 3). The accompanying woodcut

shows the doll in the monkey’s clutches, the open door in

the background revealing a palm tree and two human figures (the shorter figure represents the young mistress

greeting the adult visitor). This monkey belongs to the

exotic world of the West Indies, and it mishandles the doll

•

autumn 2013

(properly dressed in long skirt, kerchief, and bonnet) with

abandon. Upon returning to see her doll “in the paws of

the savage monkey,” the young mistress gives a “terrible

scream,” whereupon, fearing “the punishment he

deserved,” the monkey takes the doll in its mouth and

climbs up the chimney to the roof-top (this bit of misbehavior will be repeated in the humorous nineteenth-century poem The Monkey’s Frolic). The monkey willfully

takes matters into his own hands, and unlike the first mistress’ brother, shows no regret for his actions. The doll’s

current mistress runs out of the house to find the monkey

clutching her doll (now “black as soot itself could be”) up

on the roof. A servant soon arrives to shoot the monkey

dead, and the doll falls into a nearby pond, horribly

scratched and disfigured by the monkey’s paws. This monkey was given free rein, but used his power within the

household to steal and maim the prized London doll. His

bad behavior echoes the brother’s mistreatment, but his

punishment is not guilt, but death.8

This trope of a monkey mishandling a female object is

played out with a very different and humorous result in

the popular nineteenth-century picture book The Monkey’s

Frolic.9 It was first issued by the London publisher John

Harris in 1823, and was reissued on both sides of the

Atlantic through at least the 1850s. Unlike the relatively

crude woodcut relief images found in The History of a Doll

and People of All Nations, The Monkey’s Frolic has images

produced from engraved copper plates using an intaglio

process in which the image is cut into a copper plate using

sharp tools; the furrowed lines made by the tools hold the

ink, and the image is transferred onto paper using a special plate press. With its capacity for producing finely

detailed images, the intaglio method dominated the

graphic production of separately issued prints (particularly political cartoons) during the first three decades of the

nineteenth century, and its popularity extended to picture

books.10 The Monkey’s Frolic is a bit bigger than the first

two books, reflecting the greater availability of paper for

picture books by the late 1820s. Its letterpress text was

printed on a conventional hand press, making it easier to

correct any textual errors.

The story’s action takes place in a well-furnished house

in which the pet monkey is literally granted the run of the

house and free rein over his activities. Unlike the orangutan in the wild and the doll-tormenting pet, this monkey

f ig . 4 , op p o s i t e . Mischievous Pug “shaves” and binds the cat, in

The Monkey’s Frolic, a Humorous Tale (Lancaster, MA: Carter, Andrews &

Co.; Boston: Carter & Hendee; Baltimore: Charles Carter, ca.

1828–1830), leaf 2. Copper engraving, probably by Joseph Andrews,

67⁄8 x 41⁄4". Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

wa s o w i c z

•

m 0 n k e y s i n p ic t u r e s b o ok s

21

22

Imprint

•

autumn 2013

wa s o w i c z

is fully dressed (and grandly at that) in what resembles a

military uniform complete with epaulettes on his jacket,

but the ruffles on his pants signal that this power suit

might be more the stuff of childish play. Pug begins his

frolic by attempting to shave Puss the pet cat (fig. 4). Puss

is described as a female, and depicted as a naked pet,

reflecting her remove from the clothed, human-like status

of the monkey. After attempting to charm her with a

greeting, Pug resolves to shave her with a scary looking

(but actually harmless) ivory letter opener. Although Puss

tries to escape, Pug the monkey “pursued, and regardless

of struggle or prayer,/ Fast bound her, at last, to the back

of a chair.” Thus restrained, the female puss can only rely

on her wailing to get the attention and protection of the

household’s human members. The cook responds to her

mewing, but the wily Pug absconds with Puss in his arms

headed for the roof-top.

The text is always careful to soften the seemingly true

situation depicted in the illustrations. As in the tense

rooftop situation depicted in The History of a Doll, the

human members of the household try to intervene (fig. 5).

In this case, when a servant climbs a ladder to reach Pug

and his cat hostage, the monkey exercises both free will

and initiative by throwing a roof tile at his “assailant.”

Ultimately, Pug was met with laughter, not bullets, as he

wiped the soapsuds off of Miss Puss’ face “as Nurse would

a child.”11 The bottom engraving shows Pug easily walking with the cat as he would on the ground, the flying owl

in the background reminding the viewer that they are

indeed up in the air. This image of a male monkey physically holding a female cat hostage is replicated not only in

the many reissues of The Monkey’s Frolic but it also finds its

way into the wider print culture for adults in the disturbing image of The Cat’s-Paw engraved by Robert Graves

(1798–1873) after a design by British artist Edward

Henry Landseer (1802–1873).12 Landseer specialized in

humorous and sentimental depictions of animals, and his

work appeared in pictorial books for children and adults in

the nineteenth century. In this case, the male monkey is

holding his hostage’s paw onto a stove, her kittens in the

basket above witnessing the gruesome scene (fig. 6). As in

The Monkey’s Frolic, the harshness of the image is softened

by the text; the accompanying poem, describes a coquettish cat who flirts with the monkey, who being the wily

f ig . 5 , op p o s i t e . Pug throws the roof tile and carries the cat to the

chimney, in The Monkey’s Frolic, a Humorous Tale (Lancaster, MA: Carter,

Andrews & Co.; Boston: Carter & Hendee; Baltimore: Charles Carter,

ca. 1828–1830), leaf 4. Copper engraving, probably by Joseph Andrews,

67⁄8 x 41⁄4". Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

•

m 0 n k e y s i n p ic t u r e s b o ok s

23

f ig . 6 . The Cat’s-Paw, in The Forget-Me-Not (London: R. Akerman;

Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1830), 6th Plate. Copper engraving by

Robert Graves after a design by Edward Henry Landseer, 51⁄2 x 33⁄8".

Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

creature he “naturally” is, uses their familiarity to control

her paw to grab a hot chestnut roasting on the stove. The

cat retaliates by scratching the monkey and breaking his

hold; but her victory is not recorded in the illustration.

Unlike Landseer’s cat, Miss Puss does not break free,

but she does engage with Pug in a rooftop adventure. The

daredevil monkey swings with the cat onto an adjacent

rooftop, where they slide through a chimney (shades of

the ill-fated London doll), and bound into the sick room

of a man suffering from gout. These uninvited visitors literally scare the invalid into good health, and Pug is hailed

as a hero. He shakes hands (like a gentleman) with the

cured man’s doctor before returning home with Miss Puss.

In the 1840s, New York picture-book publisher Charles P.

Huestis recast the story as a cheaply-printed woodengraved picture book in which the terse rhyme is

exchanged for verbose prose. Pug becomes Jocko, and

Miss Puss becomes a French cat named Miss Minette, but

the iconography is essentially the same. The pet monkey,

24

Imprint

f ig . 7. Country Bumpkin Pug asks for directions, in Pug’s Tour through

Europe [Philadelphia?: Morgan & Yeager?, ca, 1824–1825?], 1. Copper

engraving, probably by Hugh Anderson, 41⁄4 x 31⁄2". Courtesy of the

American Antiquarian Society.

by his wily charm, occupies the ambiguous space between

willful human and subservient animal.

The monkey character gains even more ground as a fullblown tourist and would-be bon vivant in the picture book

Pug’s Tour through Europe. Although first published in

London, the edition held at the American Antiquarian

Society contains text adapted to an American audience.13

Unlike The Monkey’s Frolic, the illustrations and accompanying captions are both engraved on metal. Two of the

engravings are signed “HA” (see fig. 9) and could be the

work of Hugh Anderson (1782–1866) who was working

in Philadelphia at the time and contributed an engraving

to at least one book also containing an engraving by

Joseph Yeager, a partner in the firm Morgan & Yeager,

picture-book publishers.

This edition of Pug’s Tour is definitely an American

knock-off. American allusions are inserted in the first

verse (fig. 7): “A country Pug to New-York came,/ A raw

young yankee Squire,/ Awkward his dress, his gait the

•

autumn 2013

same,/ His full-moon cheeks on fire.”15 Pug might be fully

dressed but his attire is that of a country bumpkin—oldfashioned knee britches, vest, and frock coat—which

might do in rural Connecticut, but not New York in the

1820s. With curved walking stick in hand, he appears

fresh in town—and looks like he is asking directions of a

London beefeater (the text was changed more than the

illustrations). The text says he was “Exciting laughter and

surprise,/And something too like pity.”16 It is not an accident that Pug is posed in front of menagerie animals in

their cages; in fact an unclothed long-tailed monkey is in

the upper right, as though mimicking the monkey mimicking a man. Pug, like his unclothed counterpart, is on

display as an unusual (if not exotic) creature, engaging our

laughter and pity.

Pug goes to a tailor where he ditches his country duds

for long pants and a tailored waistcoat: “Fine cloths

bespoke. Snip knew his trade,/ And fitted him quite

handy;/ The Bumpkin grew a dashing blade,/ A first-rate

laughing dandy.”17 Not only do we see Pug in his new

outfit, it is as though the clothes direct him in a sleek,

postured attitude. The tailor is himself quite natty and

forceful, as he presides over the actions of the new Pug

(fig. 8). The tools of his trade (the scissors, the fabric, and

hanging wigs) are all in plain view. A well-dressed couple

curiously observe Pug through the window, as though

they are watching a caged monkey.

The newly outfitted Pug resolves to take “The Tour of

Europe and forsake Columbia for some years./ On board

a steam ship, Calais bound,/ the youth embark’d at Old

Slip [the Southern tip of Manhattan].”18 So although the

images closely match the English edition, care was made

to adjust the text for an American audience, turning the

English Pug into a Yankee going abroad. Pug skillfully

embraces and imitates the European locals around him. In

France, Pug offers snuff to a lady with a low bow. In

Venice, he dances with masked carnival goers, mistaking

them for apes, reminding the viewer that friendly revelers

are not necessarily friends.19

With detail worthy of a political caricature, Pug’s visit

to an Italian art gallery is lampooned (fig. 9). He is shown

examining a fine painting of St. Peter’s Basilica, the seat

of Christianity, through an eyeglass. A sculpture of the

wolf nursing Romulus and Remus is in the foreground, as

if to remind Pug that the civilization of Rome was started through the close union of pagan god, man, and animal. Pug seems too intent on appraising the painting of

the contemporary Rome to pay any attention to civilization’s (and his own) humble beginnings. The text echoes

the irony: “Paintings he’d say were so, and so,/ Sculptures

were, such, and such;/ And each he’d criticise [sic],

although/ A pig knows just as much.”20 This line essentially equates our monkey dandy with an unclothed

wa s o w i c z

•

m 0 n k e y s i n p ic t u r e s b o ok s

25

f ig . 8 . Pug tries on his new suit, in Pug’s Tour through Europe

[Philadelphia?: Morgan & Yeager?, ca, 1824–1825?], 2. Copper engraving probably by Hugh Anderson, 41⁄4 x 31⁄2". Courtesy of the American

Antiquarian Society.

f ig . 9 . Pug visits a Roman art gallery, in Pug’s Tour through Europe

[Philadelphia?: Morgan & Yeager?, ca, 1824–1825?], 7. Copper engraving probably by Hugh Anderson, 41⁄4 x 31⁄2". Courtesy of the American

Antiquarian Society.

“learned” (i.e., trained) pig. The urn to the right of the

painting bears the initial “HA” (conceivably engraver

Hugh Anderson). Pug’s European trip comes to an

abrupt end when he encounters Greeks fighting the

Ottoman Turks for their independence (a very real event

that lasted from 1821 to 1832). Our departing dandy

wishes the “Brave Greeks” well. Pug acts as a comic filter

to convey the real violence and tribulation in Greece that

was being recorded by the poet Lord Byron and the

American medical reformer Samuel Gridley Howe at the

same time.

Some thirty-five years later, a truly American monkey

emerges from the pages of The Discontented Monkey, a picture book issued just as Charles Darwin was publishing

his On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection,

and the debate concerning slavery reached a fever pitch.21

This sophisticated nineteenth-century fable is attributed

to “Klaver Oldfellah” (whose identity has not surfaced),

but its black-line wood-engraved illustrations were

designed by the well known social caricaturist Augustus

Hoppin (1828–1896). Raised in an upper-class

Providence family and trained in law at Harvard, Hoppin

quickly abandoned a legal career to pursue art.22 He particularly excelled at caricature, and his eye for poking fun

at American society is evident in his illustrations for The

Discontented Monkey. The picture book’s title signals a different type of monkey portrayal. The monkeys in the earlier books are mischievous, wily creatures graced with the

gift of mimicry; but the adjective “discontented” alludes to

the very human ability to aspire, even dream, and this

f ig . 1 0 , n e x t pag e . Monkeys paying homage to the almighty dollar, in Klaver Oldfellah, The Discontented Monkey (Boston: C. H.

Brainard; New York: Dinsmore & Co., 1859. Cover imprint: Boston:

Clark, Shepard & Brown), inner wrapper. Wood engraving by Henry

Bricher and Stephen S. C. Russell after a design by Augustus Hoppin,

67⁄8 x 51⁄4". Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

26

Imprint

•

autumn 2013

wa s o w i c z

•

m 0 n k e y s i n p ic t u r e s b o ok s

27

28

Imprint

•

autumn 2013

story is essentially a dream tale. First of all, the hero Jocko

is not a freewheeling pet or an exceptional animal functioning in a world run by humans; he lives with his mother in a monkey community complete with social gradations. Jocko yearns to live in the fashionable West End of

the wood, although his wise mother dismisses its inhabitants as mostly upstarts who seek to live close to the aristocracy. Disregarding his mother’s counsel, the aspiring

Jocko sets up household in a rotten stump, but discovers

he cannot fully participate in West End society because he

does not have a fashionably long tail; in fact, he has just a

nub of tail because his father had it cut off when he was a

baby to avoid it getting caught in a hyena trap. A frustrated

Jocko appeals to the advice of a human dervish who advises

Jocko to visit an oracle at the Temple of Terminus, which

Hoppin portrays with biting wit (fig. 10). We see the

smoky altar to the “almighty” American dollar flanked by

tall apelike soldiers (one wears an Asian straw hat and the

other a fez). The monkey pilgrims appear to represent a

cross section of classes: one female wears a fashionable

hoopskirt, and a portly male has a proper suit jacket, while

the patched pants of one prostrate pilgrim are clearly visible. Perhaps Hoppin wanted to comment on the rising

power of the American dollar around the world, as well as

its power to draw the homage of all its inhabitants around

it in ways that reform ideology, or religion, or even secular

morality, could not.

Jocko’s wish is eventually granted through the intercession of a visionary, “tail-spinning” poet (who is not pictured

and seems human), and the aspiring monkey quickly

employs the services of a “tail dresser” to get it curled to

fashionable perfection (fig. 11). The tail dressing shop is

run by a “ribbed-nosed baboon” which Hoppin portrays

with great anatomical attention. Apparently he is aware of

the various zoological studies of primates coming to the

fore at the time. Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means

of Natural Selection was published in London in November

1859, and it must have heightened awareness of primates

and their biological relationship to humans.

When Jocko discovers that his curled tail upsets his

center of balance, he goes to get it ironed out at a laundry

run by Sufferer the tailor, an orangutan (fig. 12). Once

again, Hoppin’s drawing breathes unique life into every

figure in the picture, from the calm face of Sufferer pre-

siding over the iron, to the bespectacled tailor threading

the needle, and the fleeing backside of our hero Jocko.

Tortured by the heat on his tail, Jocko runs out of the

laundry, only to have his tail mistaken by monkey firefighters as a hose, and they hold it directly to the fire.

When he realizes how badly he has misspent his life with

foolish aspirations, Jocko awakes in his mother’s habitation, and he realizes that it was all just a nightmare.

With its wordy, cumbersome prose, the real genius of

The Discontented Monkey lies in its pictures that appeal on

many levels to both children and adults. The co-publisher Shepard, Clark & Brown published both fairy tales and

fiction for children. An advertisement on the inside

wrapper for the book’s other Boston publisher, Charles

H. Brainard, describes him as a print and book publisher,

and lists portraits of celebrities for sale including the abolitionists Charles Sumner, Wendell Phillips, and William

Lloyd Garrison. As a printed artifact, The Discontented

Monkey is literally the product of an American reform

and intellectual culture that is redefining what it means to

be human.

An image of monkeys from the anonymously issued

ABC Book I sums up both the playful and liminal role that

monkey characters occupied in children’s picture books in

the first half of the nineteenth century (fig. 13).23 The

illustration shows three monkeys climbing a tree that has

a bell tied onto it with a rope (thus telling the viewer that

the tree “belongs” to a human). The rhyme caption accompanying the image reminds the reader of monkeys as a

type of humorous mirror echoing (but not quite replicating) human behavior: “The monkeys are a cunning race/

So full of antics and grimace,/ Who strut and in our faces

grin,/ As tho’ they had created been,/ To let us see as in a

glass,/ Our follies all before us pass.” 24 In this case, the

monkeys are naked animals, who play in the tree at and for

the pleasure of humans, both the ostensible, invisible

owner of the bell-entwined tree, and the human reader

viewing the image. As seen in the stories about the illfated London doll and her monkey tormentor, the frolicking monkey Pug, the Yankee traveler Pug, and Jocko the

discontented monkey, these monkeys play out aspects of

willful misbehavior, humorous misrule, ambitious mimicry, and dreamy aspiration that could be attributed to

human characters. Richard Johnson’s portrayal of the pet

f ig . 1 1 , p r e c e di n g pag e . Jocko gets his tale curled, in Klaver

Oldfellah, The Discontented Monkey (Boston: C. H. Brainard; New York:

Dinsmore & Co., 1859. Cover imprint: Boston: Clark, Shepard &

Brown), plate 4. Wood engraving by Henry Bricher and Stephen S. C.

Russell after a design by Augustus Hoppin, 67⁄8 x 51⁄4". Courtesy of the

American Antiquarian Society.

f ig . 1 2 , op p o s i t e . Jocko gets his tail ironed, in Klaver Oldfellah,

The Discontented Monkey (Boston: C. H. Brainard; New York: Dinsmore

& Co., 1859. Cover imprint: Boston: Clark, Shepard & Brown), plate 5.

Wood engraving by Henry Bricher and Stephen S. C. Russell after a

design by Augustus Hoppin, 67⁄8 x 51⁄4". Courtesy of the American

Antiquarian Society.

wa s o w i c z

•

m 0 n k e y s i n p ic t u r e s b o ok s

29

30

Imprint

•

autumn 2013

wa s o w i c z

monkey in The History of a Doll offers a severe cautionary

example of how even a pampered pet can pay with his life

for mishandling a girl’s beloved doll (amplifying the punishment received by a naughty brother for a similar

offense). Not unlike a slave, the monkey’s life was to a fair

extent expendable, and completely in the hands of its

owner. In contrast, the male monkey protagonists in The

Monkey’s Frolic, Pug’s Tour through Europe, and The

Discontented Monkey occupy an exceptional space between

humans and other animals, which includes the human

trappings of clothing and free agency. In The Monkey’s

Frolic, the prankster Pug is given free rein by his master

with no effective curbs, and as a result of his antics with

the cat, he solves the human invalid’s problem by scaring

him into good health. Though treated as an exotic oddity

by humans, the touring Pug in Pug’s Tour through Europe