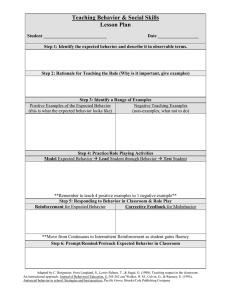

Introduction to Positive Ways of Intervening with Challenging Behavior

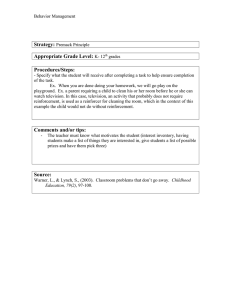

advertisement