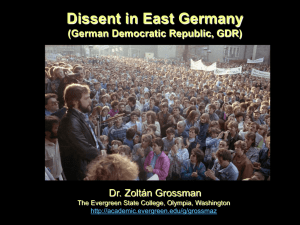

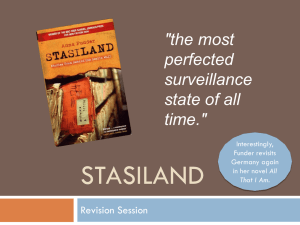

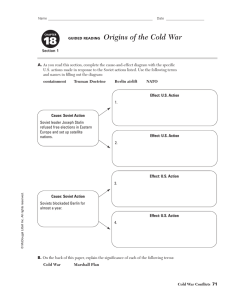

East Germany: The Stasi and De

advertisement