African Health Sciences Vol 8 Special Issue.pmd

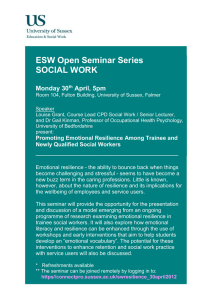

advertisement