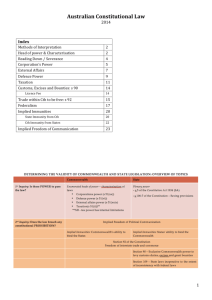

The state of fundamental legal rights in Australia

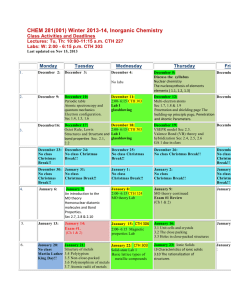

advertisement