From the Chiang Mai Initiative to an Asian Monetary Fund

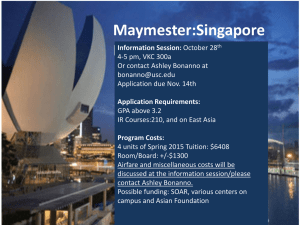

advertisement