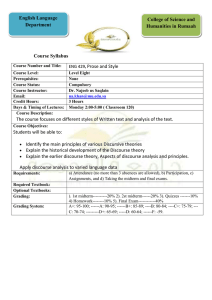

Discourse Analysis - NCRM EPrints Repository

advertisement