Effects of captopril on ventricular arrhythmias in the early and late

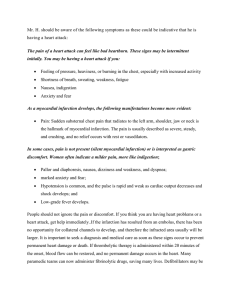

advertisement

European Heart Journal (1996) 17, 1506-1510 Effects of captopril on ventricular arrhythmias in the early and late phase of suspected acute myocardial infarction Randomized, placebo-controlled substudy of ISIS-4 A. Budaj, J. Cybulski, K. Cedro, S. Karczmarewicz, J. Maciejewicz*, M. Wisniewski* and L. Ceremuzyriski Postgraduate Medical School, Grochowski Hospital, Warsaw, Poland, "Dietla Hospital, Cracow, Poland Ventricular arrhythmias (ventricular ectopic beats per hour) occurred significantly less frequently among captopril-allocated patients than among those allocated placebo at day 3 (logarithmic scale: 0-48 ± 0-8 captopril vs 0-84 ± 1-3 placebo; F<0O03) and at day 14 (0 51 ± 10 vs 0-77 ± 1-3; /><005). The number of patients with frequent ventricular arrhythmias (more than 10 ventricular ectopic beats per hour) was also significantly lower among those allocated captopril at day 3 (7-3% vs 14-4%; /><0-05) and at day 14 (7-3% vs 14-8%; /><005). These results support the hypothesis that the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone and sympathetic system may underlie heart rhythm disturbances in acute myocardial infarction, and that early use of converting enzyme inhibitor therapy may ameliorate these disturbances. (Eur Heart J 1996; 17: 1506-1510) Key Words: Myocardial infarction, ventricular arrhythmias, ACE inhibitors, captopril, antiarrhythmic effect. Introduction logical properties of the heart leading to an increased propensity to arrhythmias'451. Angiotensin converting The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is activated enzyme (ACE) inhibitor therapy has been reported to in the acute phase of myocardial infarction and this produce antiarrhythmic effects in patients with congestive 16 71 is associated with various complications including heart failure ' , while in 11 patients with frequent 11 ventricular arrhythmias ' . It seems likely that this ventricular ectopic beats and preserved left ventricular relationship is causal since activation of the renin- systolic function captopril was not shown to suppress 181 angiotensin-aldosterone system increases systemic and ventricular ectopic activity . coronary vascular resistance, which results in a rise in Several small studies of the effects on ventricular myocardial wall stress and a fall in coronary blood flow, arrhythmias of ACE inhibitor therapy during and after augments urinary excretion of potassium and mag- acute myocardial infarction have been published. In nesium, and exerts a direct toxic effect on myocardial 1992, our group reported that captopril suppressed cells'2'31. These effects adversely modify the electrophysio- ventricular ectopic beats in the third week after myocardial infarction'91. In 1993, Pipilis et al.ll0] observed a non-significant reduction in the frequencies of idioRevision submitted 19 January 1996, and accepted 15 February ventricular rhythm and in the number of ventricular 1996. ectopic beats per hour during the first 48 h after the start The study supported by the grant CMKP-S-30/94 from Post- of treatment in acute myocardial infarction among 32 graduate Medical School, Warsaw, Poland. The results were presented at the XVII Congress of the European patients allocated captopril compared with those allo-1 cated placebo. More recently Di Pasquale et a/.'" Society of Cardiology, 20-24 August 1995 Amsterdam. reported that captopril given before thrombolysis Correspondence Andrzej Budaj, MD, Department of Cardiology, reduced the incidence of reperfusion arrhythmias, as Postgraduate Medical School, Grochowski Hospital, Grenadier6w well as of predischarge ventricular arrhythmias, as 51/59, 04/073 Warsaw, Poland. 0195-668X/96/101506+05 $18.00/0 1996 The European Society of Cardiology Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on September 30, 2016 The antiarrhythmic effect of oral captopril was studied during the early (day 3) and late (day 14) phase of acute myocardial infarction among 304 patients in a randomized placebo-controlled substudy of ISIS^t. Effect of captopril in AMI Methods Study group and treatment ISIS-4 is described in detail elsewhere'14'. Patients were eligible if symptoms of suspected acute myocardial infarction had started within 24 h and there were no clear indications for, or contraindications to, oral ACE inhibitors, oral nitrates and intravenous magnesium, each of which was tested in ISIS^t. Randomization was performed by a central 24 h telephone randomization service. A 2 x 2 x 2 factorial study design was used, with half the patients randomly allocated to receive oral captopril (initial dose 625 mg, followed 2 h later by 12-5 mg, 12 h later by 25 mg, and then 50 mg twice daily) or matching placebo for 28 days. Apart from the trial medications, routine treatment was administered at the discretion of attending physicians. Patients admitted to coronary care units at Grochowski Hospital in Warsaw and Dietla Hospital in Cracow between July 1991 and August 1993 with suspected acute myocardial infarction were considered for the arrhythmia substudy. This substudy was approved by the institutional ethical committees of both hospitals. Recording and analysis of arrhythmias in the Holter substudy Twenty-four hour Holter ambulatory monitoring was performed on day 3 ± 1 and day 14 ± 2 after admission to the CCU. Both recordings were available for reliable analysis from 304 of 469 randomized patients (the limited availability of Holter recorders prevented some patients from undergoing the monitoring). Arrhythmias were traced onto both MTM Multitechmed two channel recorders (Grochowski Hospital) and Oxford Medilog II single channel recorders (Dietla Hospital). Replay-under-visual-control analysis was conducted by physicians unaware of the patients' allocated treatment regimen. The number of ventricular ectopic beats per hour of recording time, ventricular tachycardia (defined as a sequence of three or more ventricular ectopic beats at a heart rate >110/min) were recorded as were the presence of complex ventricular arrhythmias (multifocal ventricular ectopic beats, pairs and/or ventricular tachycardia). Statistical analysis Data are presented as means with standard deviations (SD) or percentages. Ventricular ectopic beats/hour are not normally distributed in patients with acute myocardial infarction, and so the values obtained were logarithmically transformed for statistical comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS/PC+ program. Variance analysis and Student unpaired t-test were used to compare the frequency of arrhythmias in the treatment groups. The incidence of ventricular arrhythmias as a categorical variable was also compared by the chi-square test. A P value <005 was considered significant. Results Patient characteristics Baseline pre-randomization patient characteristics (Table 1) were well-balanced between the treatment groups. Patients were randomized at an average of 11 h from the onset of symptoms of suspected acute myocardial infarction. ST segment elevation of the initial ECG was present in 73% of the patients (33% in anterior leads, 38% in inferior leads alone and 2% in both or other leads). Slightly more of the patients allocated captopril had evidence of inferior infarction but this excess was not statistically significant. Following randomization, infarction was confirmed in 92% of the randomized patients. There were no significant differences in non-trial medications between the groups, except that antiarrhythmic drugs were used more often in the placebo group (16% captopril vs 30% placebo). None of these patients received any non-trial ACE inhibitor in hospital. Ventricular arrhythmias The overall prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias is shown in Table 2. More than 10 ventricular ectopic beats/hour were observed in about 10-11% of patients, ventricular tachycardia in about 2-3% and complex ventricular arrhythmia in about 10-12%, with little difference between the prevalence at day 3 and that at Eur Heart J, Vol. 17, October 1996 Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on September 30, 2016 compared with those allocated captopril from the 3rd day of myocardial infarction. Similarly, in CATS'121 the incidence of reperfusion arrhythmias was significantly reduced by giving captopril with thrombolytic therapy during the acute phase of myocardial infarction. Soogard et a/.1'31 did not observe an antiarrhythmic effect as a result of captopril administration on day 30 after myocardial infarction but in that study the drug was started on the 7th day after the onset of myocardial infarction. However, captopril induced a significant antiarrhythmic effect by 6 months, with a correlation between left ventricular dysfunction and arrhythmias. It may be that any antiarrhythmic effects as a result of ACE inhibitor therapy are greatest when treatment is started early in acute myocardial infarction. To assess more reliably the effects on arrhythmias of the early use of ACE inhibitor therapy we prospectively planned a much larger Holter arrhythmia study than had previously been conducted among a subset of patients entering ISIS-4'14'. 1507 1508 A. Budaj et al. Table 1 Clinical characteristics of patients (mean ± SD or number and percentage) No of patients with Holter monitoring Placebo 153 Statistical significance 112(74%) 58-3 ± 100 125 ± 18 80 ± 13 20(13%) 10-3 ±4-9 116(76%) 591 ±10-6 121 ± 18 84±17 16(10%) 11-5 ± 6-2 ns ns ns ns ns ns 50(33%) 61(40%) 2(1%) 37(25%) 49(32%) 55(36%) 4(3%) 44(29%) ns ns ns ns 142(94%) 138(90%) ns 76(50%) 76(50%) 77(50%) 78(51%) ns ns 54(36%) 149(99%) 118(78%) 29(19%) 25(16%) 68(44%) 145(95%) 109(72%) 37(24%) 46(30%) ns ns ns ns /><0-025 CHF = congestive heart failure. Table 2 Prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias VEBs/hour Day 3 Day 14 0 0-1-10 >10 133(43-2%) 138(45-8%) 138(46-3%) 128(43-2%) 28(10-5%) 33(10-7%) VT Complex VA 9(2-9%) 7(2-3%) 38(12-3%) 31(10-3%) VEBs = ventricular ectopic beats; VT=ventricular tachycardia; VA = ventricular arrhythmia. Table 3 Ventricular ectopic beats . h ~~' in each treatment group Logarithmic mean ± SD (and corresponding linear mean ± SD) No of patients Day 3 Day 14 Captopnl Placebo 151 0-48 ±0-8 (1-8 ±5-4) 0 51 ± 1 0 (3-2 ±2-2) 153 0-84 ± 1-3 (8-1 ±30-8) 0-77 ± 1-3 (9-2 ± 49-7) day 14. The mean number of ventricular ectopic beats. h~' was significantly lower among those allocated captopnl, both at day 3 and at day 14 (Table 3, Fig. 1). The number of patients with frequent ventricular arrhythmias (defined as ventricular ectopic beats/hour >10) was also significantly lower at day 3 and at day 14 in the captopril group (Table 4, Fig. 2). No Eur Heart J, Vol. 17, October 1996 Statistical significance /><0003 /><005 significant differences in the incidence of ventricular tachycardia or of complex ventricular arrhythmias were demonstrated. Discussion The present study demonstrates that captopril starting from the first day of suspected myocardial infarction Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on September 30, 2016 Pre-randomization data Male n Age (years) Systolic BP (mmHg) Heart rate (beats . min ~ ') Symptoms of CHF Time from pain onset (h) Electrocardiogram ST elevation, anterior ST elevation: inferior ST elevation: other No ST elevation Post-randomization data Infarction confirmed Other trial treatment in hospital Nitrates p.o. Magnesium sulphate Non-trial treatment in hospital Fibrinolytic Aspirin Nitrates i.v. Beta-blockers Antiarrhythmics Captopnl 151 Effect of captopril in AMI Table 4 Incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in each treatment group 1509 rp<0.05-, Xt Number of patients (and percentage) Captopril Placebo Statistical significance m 14.8 rvi •s 10 m -13 C VEB.h~'>10 Day 3 Day 14 Complex VAs Day 3 Day 14 VT Day 3 Day 14 11(7-3%) 11(7-3%) 22(14-4%) 22(14-8%) /><005 P<00S -.n 03 7.3 7.3 O 15(9-8%) 16(10-7%) 23(14-8%) 15(10-0%) ns ns 3(2-0%) 3(2-0%) 6(3-9%) 4(2-7%) ns ns See Table 2 for explanation of abbreviations. r- P < 0 . 0 5 - | 0.84 0.77 03 0.51 §& n = 151 n = 153 Dav3 n=151 n = 153 Dav 14 Figure 1 Frequency of ventricular ectopic beats per hour (VEB.h" 1 m e a n ± S D ) on a logarithmic scale in the captopril Q and placebo-allocated D groups as recorded on day 3 and day 14. produces antiarrhythmic effects in both early and late phases of acute myocardial infarction. These results confirm the observation in our earlier small study191 and are consistent with the trends in other studies1'0"12'. Although one small study did not observe an antiarrhythmic effect of captopril on day 30 after myocardial infarction, treatment started 7 days after myocardial infarction in that study (and a significant reduction in ventricular arrhythmias was observed at 6 months). In GISSI-2[I5) it was reported that >10 ventricular ectopic beats/hour was one of the strongest prognostic predictors in patients recovering from myocardial infarction following treatment with fibrinolytic agents. We found that captopril treatment led to a significant decrease in the number of patients with frequent ventricular ectopic beats. >10.h~'. What mechanisms may be involved in the antiarrhythmic properties of ACE inhibitors? Experimental electrophysiological evidence of direct antiarrhythmic action by ACE inhibitors is controversial'18"201, and it is likely that the metabolic t is n = 11 n = 22 Dav .3 n=ll n = 22 Dav 14 Figure 2 Percentage of patients with frequent ventricular ectopic beats (VEB.h-•> 10) in the captopril Q and placebo-allocated • groups as recorded on day 3 and day 14. action of these compounds constitutes the main mechanism of benefit. (Similarly, metabolic properties of /J-blockers'21>22' and amiodarone123'241 seem to be responsible for beneficial effects in secondary prevention after myocardial infarction, and is related to the electrical stabilization exerted by these drugs'251). ACE inhibitor therapy reduces angiotensin II production, and this results in decreased peripheral resistance, as well as a reduction in the load imposed on the heart, along with alleviation of sympathetic nervous strain'16'171. ACE inhibitors also reduce the generation of aldosterone with subsequently diminished loss of magnesium and potassium and better preservation of electrolyte balance. Blockade of the toxic effects of angiotensin II on the myocardial cells may also be important. In our study, antiarrhythmic drugs were more frequently used in the placebo group (30%) than in the captopril group (16%). The question arises as to whether this may have influenced the results. For example if these antiarrhythmic drugs produced proarrhythmic effects, increasing the number of ventricular ectopic beats, then this could bias the treatment comparisons. This seems unlikely, however, as all major trials with antiarrhythmics after myocardial infarction, including CAST12 '271, resulted in reductions in ventricular ectopic beats despite an increased mortality. In conclusion, starting captopril early in acute myocardial infarction has an antiarrhythmic effect during the early (day 3) and late (day 14) phases of acute myocardial infarction. These antiarrhythmic properties have particular clinical relevance since in the post-CAST era we are fully aware of the proarrhythmic effects of classical antiarrhythmic drugs. ACE inhibitor therapy is devoid of the above adverse effects while still being able to stabilize cardiac rhythm. This antiarrhythmic effect of ACE inhibitor therapy may play a role, along with attenuation of remodelling, in reducing mortality when ACE inhibitors are used early in acute myocardial Eur Heart J, Vol. 17, October 1996 Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on September 30, 2016 i <0.003 bo 3 1510 A. Budaj et al. infarction (as in ISIS-4[14] and in GISSI-3[28]) as well as long-term following myocardial infarction'29'301. The authors thank Dr Rory Collins and Dr Marcus Flather for valuable comments and revision of the manuscript. References Eur Heart J, Vol. 17, October 1996 Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on September 30, 2016 [1] Michorowski B, Ceremuzynski L. The renin-angiotensinaldosterone system and the clinical course of acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 1983; 4: 259-64. [2] Ceremuzynski L. Hormonal and metabolic reactions evoked by acute myocardial infarction. Circ Res 1981; 48. 767-76. [3] McAlpine HM, Morton JJ, Leckie B, Rumley A, Gillen G, Dargie HJ. Neuroendocrine activation after acute myocardial infarction. Br Heart J 1988; 60: 117-24. [4] James MA, Jones JV. Systolic wall stress and ventricular arrhythmia: the role of acute change in blood pressure in the isolated working rat heart. Clin Sci 1990; 79: 499-504. [5] Sideris DA, Kontoyannis DA, Michalis L, Adractas A, Moulopoulos SD. Acute changes in blood pressure as a cause of cardiac arrhythmias. Eur Heart J 1987; 8. 45-52. [6] Cleland JGF, Dargie HJ, Hodsman GP et al. Captopnl in heart failure. A double blind controlled trial. Br Heart J 1984, 52: 530-5. [7] Webster MWI, Fitzpatrick MA, Nicholls MG, Ikram H, Wells JE. Effect of enalapril on ventricular arrhythmias in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1985; 56: 566-9. [8] Steinman RT, Gilley D, Gunther S, Fromm B, Lehmann M. Effect of oral captopril on premature ventricular complexes in patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Cardiol 1993; 16: 105-8. [9] Budaj A, Cedro K, Cybulski J, Ceremuzynski L. Angiotension converting enzyme inhibitors as antiarrhythmic drugs in acute myocardial infarction. Arch Turk Soc Cardiol 1992; 20: 201. [10] Pipilis A, Flather M, Collins R et al. Effects on ventricular arrhythmias of oral captopnl and of oral mononitrate started early in acute myocardial infarction: results of a randomised placebo controlled trial. Br Heart J 1993; 69: 161-5. [11] Di Pasquale P, Paterna S, Cannizzaro S, Bucca V. Does captopril treatment before thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction attenuate reperfusion damage? Short-term and long-term effects. Int J Cardiol 1994; 43: 43-50. [12] Kingma JH, van Gilst WH, Peels CH, Dambrink J-HE, Verheugt FWA, Wielenga RP for the CATS investigators. Acute intervention with captopril during thrombolysis in patients with first anterior myocardial infarction. Results from the Captopnl and Thrombolysis Study (CATS). Eur Heart J 1994; 15: 898-907. [13] Sogaard P, Gotzsche CO, Ravkilde J, Norgaard A, Thygesen K. Ventricular arrhythmias in the acute and chronic phases after acute myocardial infarction. Effect of intervention with captopril. Circulation 1994; 90: 101-7. [14] ISIS-4 Collaborative Group. ISIS-4: A randomised tnal assessing early oral captopril, oral mononitrate, and intravenous magnesium sulphate in 58,050 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1995; 345: 669-85. [15] Maggioni AP, Zuanetti G, Franzosi MG et al. and GISSI-2 Investigators. Prevalence and prognostic significance of ventricular arrhythmias after acute myocardial infarction in the fibrinolytic era. GISSI-2 results. Circulation 1993; 86: 312-22. [16] Flather MD, Pipilis A, Conway M et al. for the ISIS Pilot Study Collaborators' Group. Early captopril treatment reduces angiotensin II levels after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 19: 380A. [17] Ray GS, Pye M, Oldroyd KG et al. Early treatment with captopril after acute myocardial infarction. Br Heart J 1993; 69-215-22. [18] Linz W, Scholkens BA, Han YF. Beneficial effect of the converting enzyme inhibitor, ramipnl, in ischemic rat hearts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1986; 8: 91-9. [19] Kingma JH, de Graeff PA, van Gilst WH, van Binsbergen E, de Langen CDJ, Wesseling H. Effects of intravenous captopril on inducible sustained ventricular tachycardia one week after expenmental infarction in the anaesthetized pig Postgrad Med J 1986; 62 (Suppl I): 159-63. [20] Hemsworth PD, Pallandi RT, Campbell TJ. Cardiac electrophysiological actions of captopril: lack of direct antiarrhythmic effects. Br J Pharmacol 1989; 98: 192-6. [21] Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, Collins R, Sleight P. Beta Blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomised trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1985; 27 355-71. [22] ISIS-1 Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of intravenous atenolol among 16027 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-1. Lancet 1986; ii: 57-66. [23] Burkart F, Pfisterer M, Kiowski W, Follath F, Burckhardt D, Jordi H. Effect of antiarrhythmic therapy on mortality in survivors of myocardial infarction with asymptomatic complex ventricular arrhythmias. Basel Antiarrhythmic Study of Infarct Survival (BASIS). J Am Coll Cardiol 1990, 16: 1711-18. [24] Ceremuzynski L, KJeczar E, Krzeminska-Pakula ME et al. Effect of armodarone on mortality after myocardial infarction: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 20: 1056-62. [25] Ceremuzynski L. Secondary prevention after myocardial infarction with class III antiarrhythmic drugs. Am J Cardiol 1993; 72: 82F-86F. [26] The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppresion Trial (CAST) Investigators. Preliminary report: effect of encainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomised trial of arrhythmia suppresion after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1989; 321: 406-12. [27] Greene HL, Roden DM, Katz RJ, Woosley RL, Salerno DM, Henthorn RW and the CAST Investigators. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppresion Trial: first CAST . . . then CAST-II. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 19: 894-8. [28] Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravivenza nell'Infarto miocardico. GISSI-3: Effects of lisinopril and transdermal glyceryl trinitrate singly and together on 6-week mortality and ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1994; 343: 1115-22. [29] The Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study Investigators. Effect of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. Lancet 1993; 342: 821-8. [30] Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moye LA et al. on behalf of the SAVE investigators. The effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction following myocardial infarction: Results of the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Trial. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 669-77