2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry: GFP Discovery & Development

advertisement

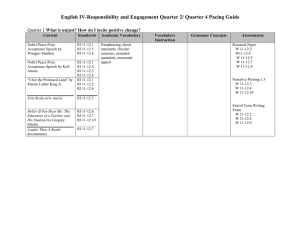

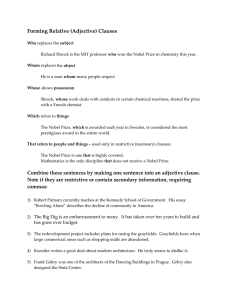

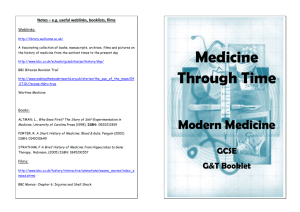

2008 nobel Laureates The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2008 Osamu Shimomura University of california, san diego J. Henriksson/SCANPIX tom kleindinst/marine biological laboratory “for the discovery and development of the green fluorescent protein, GFP” Martin Chalfie Roger Y. Tsien 1/3 of the prize 1/3 of the prize 1/3 of the prize Born: 1928 Born: 1947 Born: 1952 Birthplace: Japan Birthplace: United States Birthplace: United States Nationality: Japanese citizen Nationality: US citizen Nationality: US citizen Current position: Professor Emeritus, Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA, and Boston University Medical School, Massachusetts, USA Current position: William R. Kenan Jr Professor of Biological Sciences, Columbia University, New York, New York, USA Current position: Professor, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA chemistry 7 Copyright © Nobel Web AB 2008. Nobelprize.org, Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize medal design mark are registered trademarks of the Nobel Foundation. 2008 nobel Laureates Phantatomix/Science Photo Library Speed read: Illuminating biology T he discoveries awarded the one-hundredth Nobel Prize in Chemistry are a shining example of how fundamental research in one area of science can sometimes lead to highly beneficial applications in another. In this case, finding the key to how a marine organism produces light unexpectedly ended-up providing researchers with a powerful array of tools with which to visualise cell biology in action. Osamu Shimomura purifies a blue luminescent protein from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria that he names aequorin; he also isolates a protein displaying bright green fluorescence that is later named green fluorescent protein (GFP) 1962 The story begins with Osamu Shimomura’s research into the phenomenon of bioluminescence, in which chemical reactions within living organisms give off light. While studying a glowing jellyfish in the early 1960s he isolated a bioluminescent protein that gave off blue light. But the jellyfish glowed green. Further studies revealed that the protein’s blue light was absorbed by a second jellyfish protein, later called green fluorescent protein (GFP), which in turn re-emitted green light. The ability of GFP to process blue light to green (its fluorescence) was found to be integral to its structure, occurring without the need for any accompanying factors. In 1988, Martin Chalfie heard about GFP for the first time, and realised that its ability for independent fluorescence could perhaps make it an ideal cellular beacon for the model organisms he studied. Using molecular biological techniques, Chalfie succeeded in introducing the gene for GFP into the DNA of the small, almost transparent worm Caenorhabditis elegans. GFP was produced by the cells, giving off Martin Chalfie hears about GFP for the first time, and realises it could be used to map proteins in the transparent nematode worm, Caenorhabditis elegans 1979 Shimomura shows that GFP contains a special chromophore, a chemical group that absorbs and emits light 1988 1992 Chalfie obtains the GFP gene from Douglas Prasher, and Chalfie’s PhD student Ghia Euskirchen expresses it in Escherichia coli – the bacteria glow green in UV light without the addition of any other factors Timeline: Milestones for the 2008 Nobel Laureates in Chemistry, Osamu Shimomura, Martin Chalfie & Roger Y. Tsien. 8 chemistry Copyright © Nobel Web AB 2008. Nobelprize.org, Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize medal design mark are registered trademarks of the Nobel Foundation. 2008 nobel Laureates Tsien lab, university of California, San Diego its green glow without the need for the addition of any extra components, and without any indication of causing damage to the worms. Subsequent work showed that it was possible to fuse the gene for GFP to genes for other proteins, opening-up a world of possibilities for tracking the localisation of specific proteins in living organisms. The opportunities offered by GFP were immediately obvious to many, as was the desirability of extending the range of available tags. Roger Tsien first studied precisely how GFP’s structure produces the observed green fluorescence, and then used this knowledge to tweak the structure to produce molecules that emit light at slightly different wavelengths, which gave tags of different colours. In time, his group added further fluorescent molecules from other natural sources to the tag collection, which continues to expand. Complex biological networks can now be labelled in an array of different colours, allowing visualisation of a multitude of processes previously hidden from view. Chalfie expresses GFP in C. elegans and shows it can be used to track the location of specific proteins 1994 Roger Tsien shows how the GFP chromophore is formed in a chemical reaction that requires oxygen, without the help of other proteins Mikhail Matz and Sergei Lukyanov discover six GFP-like proteins in fluorescent corals, including a red protein called DsRED 1994–1998 Tsien and collaborators tweak the structure of GFP to produce new variants that shine more strongly and produce different colours, such as cyan, blue and yellow 1999 2000–2002 Tsien produces stable variants of DsRED that glow in shades of red, orange and pink – complex biological networks can now be labelled using all the colours of the rainbow chemistry 9 Copyright © Nobel Web AB 2008. Nobelprize.org, Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize medal design mark are registered trademarks of the Nobel Foundation. 2008 nobel Laureates In his own words: Osamu Shimomura Tom Kleindist/Marine Biological Laboratory “To get success, everybody has to overcome any difficulty on the way.” Osamu Shimomura can speak from experience. As a teenager living 12 kilometres away from Nagasaki, he felt the blast of the atomic bomb explosion in August 1945. “I was soaked by black rain. So, I was contaminated by the radioactivity, a lot of strong radioactivity. But fortunately still I’m alive.” “I don’t do my research for application or any benefit. I just do my research to understand why jellyfish luminesce” Osamu Shimomura holding some of the hundreds of thousands of jellyfish specimens that he collected from Friday Harbor. The thousands of scientists worldwide who have benefited from the fruits of Shimomura’s labours will no doubt share his sentiment. Thanks to his discovery of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in jellyfish they have one of the most important tools at their disposal for visualizing life at the microscopic level; although Shimomura is quick to point out that there was only ever a single purpose behind his studies. “I don’t do my research for application or any benefit. I just do my research to understand why jellyfish luminesce, and why that protein fluoresces.” jellyfish did he need to collect? “Our schedule was 50,000 per summer, in one or two months.” These remarkable expeditions took place every summer for 19 years, collecting a staggering 850,000 jellyfish in total. “That’s classical biochemistry, not genetics or something like that,” says Shimomura. Osamu Shimomura Discovering GFP in jellyfish took considerable effort. “What we needed to do to study that protein is we have to get large amounts of that protein. So, we collected huge numbers of jellyfish by going to Friday Harbor, Washington, every summer.” Just how many When Osamu Shimomura started studying glowing jellyfish, he had no idea that it would lead to a scientific revolution. Shimomura says that GFP is one of many, still undiscovered, molecules in nature that emit light, but he fears that the demands of carrying out such labour intensive and uncertain research will deter young scientists from looking for them. “They prefer easier research. And they prefer research subjects that you can see the results; that you are sure to get the results.” So, what advice would Shimomura give to young people who are interested in entering science? “Study whatever they are interested in, and don’t give up on the way until they finish the subject. Good subjects have a lot of difficulty. If one gives up, on the way; that’s it, that’s finished.” By way of illustrating his philosophy on never finishing until the job is done, Shimomura continues to work in a laboratory set up in the basement of his house, despite officially retiring in 2001. Recently he has been working on writing papers, and also helping other people, but he resigns himself to the inevitable change that will result from being awarded the Nobel Prize. “I think it’s hopeless to work out of the laboratory for the next several months, I guess.” This article is based on a telephone interview with Osamu Shimomura following the announcement of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. To listen to the interview in full, visit http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/2008/shimomura-interview.html 10 chemistry Copyright © Nobel Web AB 2008. Nobelprize.org, Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize medal design mark are registered trademarks of the Nobel Foundation. 2008 nobel Laureates In his own words: Martin Chalfie Looking back at the moment 20 years ago when he first heard about green fluorescent protein (GFP) in a seminar, Chalfie recalls his instant realisation that GFP could be used as a cellular beacon in his studies in the nematode worm, known as Caenorhabditis elegans. “One of the great things about working on C. elegans was the fact that it was transparent, and so when I first heard that seminar describing GFP, and realised, ‘I work on this transparent animal, this is going to be terrific! I’ll be able to see the cells within the living animal’.” The story from initial thought to seeing cells glow in C. elegans involved an extraordinary chain of events over the following two years. Chalfie contacted a researcher called Douglas Prasher who was studying GFP, and they agreed that once Prasher had cloned the gene that encodes GFP they would see if they could make it glow in C. elegans. But while Prasher finished cloning the GFP gene, Chalfie had taken a sabbatical, moving from Columbia University to the University of Utah to work with his then new wife. “When he finished the cloning, he got in touch with me, or he tried to,” recalls Chalfie. Prasher tried to contact Chalfie at Columbia University, and then at the University of Utah, “…but someone must have The Caldwell Laboratory, University of Alabama F or many scientists, the phone call from a Nobel Prize Awarding Institution informing them that they have been awarded the Nobel Prize must rank as one of the most important moments of their lives. Martin Chalfie will remember the moment somewhat differently. A recent change of ring tone on his home phone meant he slept through the call from Stockholm, thinking it was for someone else. Chalfie laughs when recalling how he received the happy news. “I woke up, and I realised that they must have given the Prize in Chemistry, so I simply said, ‘Okay, who’s the schnook that got the Prize this time?’ And so I opened up my laptop, and I got to the Nobel Prize site and I found out I was the schnook!” C. elegans glowing with green fluorescent protein. answered the phone and said something to the effect of ‘Marty Chalfie, never heard of him’,” recalls Chalfie. “And so Douglas Prasher got the idea that I had dropped out of science. He didn’t tell me because he didn’t think I was interested anymore.” Chalfie says fortune eventually shone on him after an opportune search of a medical database revealed that Prasher had cloned GFP, and the pair re-established contact. By that time, several research groups were investigating whether GFP could glow in other organisms. However, through no fault of their own, the manner in which they were excising Prasher’s GFP gene to create more of the gene themselves was creating a protein that didn’t glow. “That fragment had extra little bits of sequence on either end,” says Chalfie. “Apparently, it’s those sequences that were poison. The extra DNA interfered with the protein production.” Chalfie, on the other hand, had done things differently. “We simply amplified exactly the coding sequence from the clone, and didn’t have any of the extra DNA.” When Chalfie tested whether his GFP was working, it glowed. “I work on this transparent animal, this is going to be terrific! I’ll be able to see the cells within the living animal” Given the unlikely chain of events, and the manner in which he discovered the news about his Nobel Prize, Chalfie can be forgiven for wondering if he is still sleeping. “I’ll try to wake up tomorrow and say that it wasn’t a dream!” This article is based on a telephone interview with Martin Chalfie following the announcement of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. To listen to the interview in full, visit http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/2008/chalfie-interview.html chemistry 11 Copyright © Nobel Web AB 2008. Nobelprize.org, Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize medal design mark are registered trademarks of the Nobel Foundation. 2008 nobel Laureates In his own words: Roger Tsien L A love of pretty colours can be said to have been the driving force in Tsien’s research career. “I have to say I myself do not find pipetting colourless droplets of liquid from one plastic tube to another awfully inspiring.” says Tsien. “At least without having to worry about whether the work would be successful in 5 or 10 or 20 years, I could get some direct aesthetic pleasure out of the experiments as I went along.” When asked to comment on the observation that this Nobel Prize in Chemistry is being awarded for work that is basically involved in cell biology, Tsien notes that it’s an area that has been categorised as being chemical biology, biochemistry, or as Tsien sometimes calls it, “We try to build molecules to solve problems” Roger Tsien’s range of fluorescent proteins have brought some colour to laboratory work. molecular engineering, “at least our approach to it, because we try to build molecules to solve problems.” Does Tsien worry about these academic labels? “I try not to,” he replies, but adds that it becomes dangerous “when students let themselves get pigeon-holed, or let their thought processes get pigeon-holed, and they say ‘Oh, I could never do that, that’s chemistry. I don’t know any chemistry’.” It’s surprising how often biologists develop an attitude about chemistry or chemists an attitude about biology, says Tsien, which unfortunately creates an “instinctual fear that, ‘Oh, that’s a subject I can’t do, and nobody should expect me to know how to do, and so I will just not pay any attention to questions that lead me in that direction’.” If there is one thing that Tsien has illustrated over the years, it’s the importance of being illuminated by any direction the subject that you are interested in takes you. Tsien Lab, University of California, San Diego As an adult chemist, Tsien has been instrumental in making the green fluorescent protein a more effective beacon for visualising processes inside cells. By understanding what made GFP glow and by tweaking the structure he could create molecules that emit light at slightly different wavelengths, producing tags of different colours. From the tens of thousands of papers that have been published using the probes he has developed, Tsien finds it difficult to single out any of the applications that he likes the most. One of the “showiest applications”, he says, is the trick of painting neurons in a whole kaleidoscope of colours – known as the brainbow. Tsien Lab, University of California, San Diego ike many Nobel Laureates, Roger Tsien says his love of science began at an early age, carrying out chemistry experiments at home, accompanied with “a mixture of fear in my parents and a little bit of encouragement”. By the relatively early age of 9 or 10, he knew he wanted to be a scientist. “I think I did go through the usual smallchild phase of imagining being a fireman and so on, but yeah, I think being a scientist was more of a possibility for me than probably for most kids.” Scientists can now use a palette of different coloured tags to visualise processes inside cells. This article is based on a telephone interview with Roger Tsien following the announcement of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. To listen to the interview in full, visit http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/2008/tsien-interview.html 12 chemistry Copyright © Nobel Web AB 2008. Nobelprize.org, Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize medal design mark are registered trademarks of the Nobel Foundation.