Seeing the Light: Lysander Spooner`s Increasingly Popular

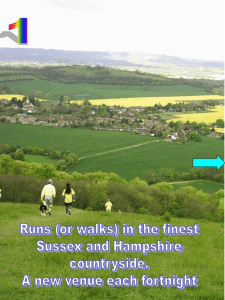

advertisement