Bank Branches in Supermarkets - Federal Reserve Bank of New York

advertisement

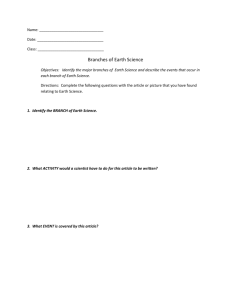

December 1996 Volume 2 Number 13 Bank Branches in Supermarkets Lawrence J. Radecki, John Wenninger, and Daniel K. Orlow The largest U.S. commercial banks are restructuring their retail operations to reduce the cost disadvantage resulting from a stagnant deposit base and stiffer competition. As part of this effort, some banks are opening “supermarket,” or “in-store,” branches: a new type of banking office within a large retail outlet. An alternative to the traditional bank office, the supermarket branch enables banks to improve the efficiency of the branch network and offer greater convenience to customers. Although the largest U.S. commercial banks have enjoyed strong earnings in recent years, they are under considerable pressure to restructure their retail operations. A stagnant deposit base and stiffer competition in the marketplace for financial services have made the overhead costs of an extensive branch network increasingly onerous. To cut costs and remain competitive, these banks are deploying phone centers, introducing the next generation of automated teller machines (ATMs), and offering customers the option to bank at home or the office from a personal computer. These electronic channels for the delivery of banking services are making visits to the branch increasingly unnecessary for routine transactions. As part of their restructuring efforts, commercial banks are rethinking the concept of a branch office. An alternative to the traditional office is a scaled-down, full-service branch located within a large retail outlet, often called a “supermarket,” or “in-store,” branch. This new type of office enables banks to improve the efficiency of the branch network and realize savings from their investment in phone centers and ATMs.1 According to industry analysts, about 3,500 supermarket branches are now in operation out of a total of 50,000 commercial bank branch offices.2 Some of the largest bank holding companies have taken the lead in introducing supermarket branches (see table). Moreover, supermarket branches will become increasingly common in the next two to three years as several large banks carry out their announced plans to open hundreds more such offices. In this edition of Current Issues, we describe the operational and strategic considerations that have prompted banks to use this new branch design, including the potential to reduce costs and expand customer bases. We then review some relevant policy issues that emerge from this new and growing approach to retail banking.3 Banks’ Cost Disadvantage Banks’ declining role as holders of household savings has resulted in a high cost structure for their branch operations. After rising to a peak of 38 percent at yearend 1974, deposits at banks, thrifts, and credit unions—measured as a share of the household sector’s financial wealth—have fallen by a little more than half, to 17 percent at year-end 1995 (see chart). The costs of a typical branch office can be used to illustrate how a static deposit base creates a competitive disadvantage for banks relative to other financial intermediaries. A typical branch has total annual direct expenses on the order of $700,000, of which the largest CURRENT ISSUES IN ECONOMICS AND FINANCE Leading Banks in Supermarket Branching as of June 30, 1995 Bank Holding Company BankAmerica Corporation Wells Fargo & Company Fifth Third Bancorp BancOne Corporation NationsBank Corporation National Commerce Bancorp Mellon Bank Corporation National City Corporation Bank of Tokyo Zions Bancorp Number of Supermarket Branchesa Supermarket Branches as a Percentage of the Bank’s Total Branches 126 6.1 88 4.6 82 16.9 71 4.5 68 3.1 47 58.0 35 7.9 29 27 25 3.1 9.5 19.1 tage. If a bank had a larger pool of deposits over which to spread its fixed expenses, the cost of the branch system would be proportionately less burdensome. Banks have tried to reduce their cost disadvantage by identifying and reducing inefficiencies in their retail operations. For instance, branch managers track the volume of teller-window transactions at each office by day of the month, day of the week, and hour of the day. The anticipated volume of customer traffic is used to set schedules for full- and part-time teller staff at each branch location. Retail management indicates, however, that it has squeezed out nearly all the costs it can from the existing system while still providing a high level of customer service.7 Supermarket Branches To cut costs, expand market share, and offer customers greater convenience, banks are testing new designs and locations for their branches. One new type of branch office is a supermarket, or in-store, branch—a full-service office operating in leased space, usually located within a giant supermarket of 50,000 or more square feet attracting 15,000 or more shoppers each week. For the convenience of bank customers, it is open seven days a week and most evenings, like the supermarket. Source: SNL Branch Migration DataSource, version 1.5. aIncludes branches with zero deposits. component is staff compensation (for twelve or so fulltime-equivalent employees).4 The cost of the building itself represents the next largest component of these total direct expenses, and the remainder comprises such items as electricity, supplies, and property maintenance. On top of direct expenses are indirect operating expenses, incurred by the head office or other centralized functions for such items as computing, preparation and mailing of monthly statements, and advertising. These indirect expenses are roughly equal to direct expenses, bringing the total annual operating expenses of a branch to $1.4 million.5 An in-store branch occupies 400 to 600 square feet, compared with a traditional branch’s 5,000. A typical unit is located near the store entrance or checkout lanes and features two teller windows, two stations at a counter to open accounts, one or two ATMs, and direct connections to the phone center. It often has a single office to hold private consultations. Some banks also equip their in-store branches with high-tech devices such as a video phone or an automated loan machine. Supermarket branches can be built and installed at a comparatively low cost—$200,000 to $300,000, or one-fifth the cost of setting up a conventional branch. About $60,000 to $100,000 of this amount covers construction costs, and the remainder is for equipment, most of which can be removed and reinstalled elsewhere. Hence, only the construction costs represent a sunk expense. The operating expenses are estimated to be $350,000 annually, compared with $700,000 or more for a traditional branch, even though the supermarket branch is open many more hours each week. A supermarket branch can therefore attain the same level of profitability as a conventional branch with slightly less than half the account and deposit volumes. The dollar volume of deposits at a typical branch is about $50 million, over which the $1.4 million of noninterest expenses must be spread. In percentage terms, annual operating or noninterest expenses therefore equal 2.8 percentage points of deposits. To cover these costs, a margin of 280 basis points must be maintained between interest expense and interest earnings, less noninterest revenue received from account fees and other charges. 6 In contrast, a typical money market mutual fund, a close substitute for a savings deposit, has an expense ratio of around 50 basis points. Thus, a bank’s cost disadvantage here is substantial and could be as much as 200 basis points. Similarly, a short-term bond mutual fund, a possible substitute for a time deposit, has an expense ratio of 80 to 100 basis points, but also a higher expected rate of return. Again, a bank appears to be working under a serious cost disadvan- FRBNY Selling and Staffing. The foot-traffic passing through the supermarket is a critical element of what makes an in-store branch work. Members of a broad cross-section of households residing within six miles of a large suburban supermarket come in to shop two or 2 and new accounts, management uses compensation packages that include commissions or bonuses linked to individual or branch performance. three times a week. Frequent shopping trips thus create opportunities for a bank to open accounts with and offer services to individuals who would otherwise not enter one of its traditional branches. Opportunities also arise to sell additional services to existing customers, who typically visit a supermarket more often than a In addition to providing more selling opportunities, supermarket branches offer greater operational efficiencies. For example, in-store branches are less expensive to operate in part because they use fewer employees— about six full-time equivalents in contrast to twelve at a conventional branch. Staff members cover for each other and are largely interchangeable. This flexibility is necessary because at many times only two employees will be working at the branch. Consequently, there is no sharp division of tasks among tellers, platform personnel, and branch management. Moreover, the branch manager typically has less management responsibility and a smaller range of duties than at a traditional branch. As a result, there is essentially one job at a supermarket branch. Supermarket branches can be built and installed at a comparatively low cost—one-fifth the cost of setting up a conventional branch. conventional branch. To take full advantage of these opportunities, branch staff will circulate through the store in order to win new accounts and sell banking products. Strategic Considerations. The supermarket and the bank see in-store branches as mutually beneficial. The supermarket chain expects increased sales as more of the bank’s customers choose to shop at a store housing a branch: the greater the bank’s market share in the region served by the supermarket chain, the larger the potential boost to sales. The revenue received from renting space to the bank is usually viewed as somewhat incidental. From its side of the alliance, the bank expects to gain from the supermarket’s flow of shoppers. Banks seek out chains that have a high proportion of super-size stores: the larger the store, the greater the flow of potential bank customers. Banks realize that they must develop a more salesoriented culture among their staff if the in-store branches are to succeed. To find employees who thrive on customer contact, personnel departments are reportedly adjusting their search procedures and increasingly emphasizing a background in retail sales and customer relations. To sustain the staff ’s efforts to generate sales Distribution of Total Financial Assets Held by the Household Sector 1952-95 Cumulative percentage 100 The supermarket-bank alliances tend to be exclusive within a state or metropolitan area. The supermarket chain prefers a single large bank to put branches in its stores because negotiating with one bank is much simpler than negotiating with several, and the chain can more effectively promote the addition of a single partner’s branches at all its locations. The bank, in turn, is looking for a supermarket chain with a presence throughout a marketing area so that it too can more efficiently advertise the combination. As a result, agreements between the largest players in a geographic area—both supermarket chains and banks—are becoming somewhat common. Pension fund reserves 80 Other 60 Corporate equity Mutual fund shares 40 Credit market instruments 38.2 20 0 1952 55 Deposits 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 Supermarket branching can be used by banks as both an offensive and a defensive strategy. On the offensive side, a bank opening in-store branches can enter a market or expand at relatively low cost. In-store branching can also serve as a defensive strategy because only a very limited number of large supermarket chains operate in any one state or metropolitan area. By forming an exclusive arrangement with one chain, a bank may hinder local competitors and potential out-of-state entrants Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Flow of Funds Accounts. Notes: The chart reports fourth-quarter data for each year. For the percentage share of deposits, the numerator is the sum of demand, savings, and time deposits at commercial banks, thrifts, and credit unions, plus currency in the hands of the household sector; the denominator is the total financial assets of the household sector less equity in unincorporated business and security credit. The household sector includes nonprofit organizations. “Other” includes life insurance reserves, investments in bank personal trusts, equity in unincorporated business and security credit, and miscellaneous assets. 3 CURRENT ISSUES IN ECONOMICS AND FINANCE from following the same low-cost strategy for penetrating a market area on a large scale. in the banking industry could eventually tilt toward larger institutions. Banking Kiosks. In addition to opening fullservice, in-store branches, banks are installing limitedservice kiosks inside supermarkets and giant discount stores. A kiosk, occupying less than 100 square feet of space, consists of one or two ATMs, a dedicated connection to the phone center, and occasionally some other self-service device, but it has no teller window. During peak shopping hours, the kiosk is staffed by one or two employees, who spend much of their time circulating among shoppers to provide information and assist in the opening of new accounts. Some large retail banks will soon have numerous kiosks in place to supplement their network of full-service, in-store branches. Kiosks are often installed in the smaller supermarkets that do not generate the shopper flows necessary to sustain a true in-store branch. This practice allows both partners to promote the bank’s presence, in the form of either a full- or a limited-service location, at every store in the chain. The shift to supermarket branches also raises a number of more immediate issues, including the effects on competition and the public’s access to financial services. The Effects on Competition. As part of its assessment of the effects of proposed mergers and acquisitions on competition, the Federal Reserve calculates an index of market concentration (the HerfindahlHirschman Index, or HHI) for each geographical market in which the combining banks operate. A higher HHI suggests a less competitive market. The competitive effects of a proposed merger that produces a high value of the HHI or increases the HHI significantly are subject to careful analysis by the Federal Reserve.8 In principle, the popularization of supermarket branching should make markets more competitive for any given value of the HHI (Neill and Danforth 1996). The lower cost structure of an in-store branch implies a lower barrier to entry or expansion. The heightened threat of entry or expansion by other banks should encourage the banks already serving a market to behave more competitively. Kiosks, which go by names such as express centers, express branches, or in-store sales kiosks, are classified by the banking agencies as off-site ATM locations; they Banks are, in fact, using the new lower cost branch design to increase the density of their branch networks and expand their geographical reach. For example, People’s Bank, most of whose branch offices are located in Fairfield County, Connecticut, has announced plans in alliance with the Stop & Shop chain to open forty-five in-store branches during a two-anda-half-year period in all parts of the state, including those counties where it does not currently have a presence (People’s Bank 1996). This expansion would tend to increase competition both in areas in which People’s Bank is already operating, as rival banks strive to maintain market share, and in those areas it is entering, where the HHI should fall as a result of its entry. Banks are . . . using the new lower cost branch design to increase the density of their branch networks and expand their geographical reach. are not officially considered to be branches. Press reports, however, often refer to them as supermarket branches, failing to distinguish them from full-service locations. Another example of this strategy is BankAmerica’s long-distance de novo entry into Chicago. By forming an alliance with Jewel-Osco, the largest supermarket chain in metropolitan Chicago, BankAmerica will open fifty supermarket branches before year-end 1996 (American Banker 1996). The large-scale entry of BankAmerica would also be expected to cause the HHI to fall and the level of competition to rise in the Chicago market. Policy Issues The advent of supermarket branches raises several issues, some theoretical or long-run in nature, others more practical and immediate. Among the long-run issues is the impact this new type of branch office will have on the economies of scale, scope, and distribution in retail banking. The switch to lower cost, in-store branches raises efficiency, which should benefit bank customers. At the same time, the new type of branch office and the alliances with the largest supermarket chains together imply a shift in a bank’s cost structure and possibly an increase in the size of a bank necessary to achieve the greatest cost efficiency now attainable. If such a shift were to occur as supermarket branching gains in popularity, the size distribution of institutions In the longer run, however, increases in the level of competition in local banking markets brought about by supermarket branching may not be sustained. For example, if the two or three largest banks in a particular area open a large number of supermarket branches and their deposit shares increase proportionately with the 4 FRBNY expansion of their branch networks, the resulting increase in retail deposit concentration in the local market could eventually lead to a higher HHI and subdued competition. banks are attempting to reduce costs and afford greater convenience to their household customers. This approach offers potential benefits to both the bank and the supermarket chain in the form of increased customer traffic and joint promotions. At the same time, supermarket branching raises important public policy issues, such as those concerning its effects on competition in local banking markets and on the public’s access to banking services. Moreover, local markets could even become much more concentrated over time. If the new type of branch office proves to be cost-effective and popular with the public, smaller banks may lose deposits and see average deposits per branch fall below their break-even point. The profitability of these smaller banks may decline enough to convince them to exit the industry, a development that could result in more concentrated and less competitive markets. Furthermore, by allying with the two or three dominant supermarket chains in an area, the largest banks could prevent potential competition from expanding through the in-store branch strategy. Endnotes 1. Orlow, Radecki, and Wenninger (1996) discuss in detail the movement to electronic delivery channels for retail banking services and how it is integrated strategically with the introduction of supermarket branches. 2. The data collected by the banking agencies do not distinguish instore branches from traditional branches. Meeting the Public’s Need for Banking Services. In evaluating merger and acquisition applications, the Federal Reserve considers how well the public’s banking needs are being met. As part of the review process, it seeks comments from residents of the communities that the applying banks serve. In fact, community representatives have opposed several proposed mergers in recent years on the grounds that prospective branch office closings would seriously reduce the availability of banking services to residents of certain low- and moderate-income communities. 3. Our discussion of supermarket branches is from the perspective of broad industry trends. Many individual institutions will not, of course, follow the general patterns. 4. Much of the information on in-store branches was obtained at an industry conference on “Advances in Supermarket Branching” held on April 24-26, 1996, in Chicago. In-store branching has also been the subject of numerous articles in the American Banker during the past few years. 5. The costs of branch operations cannot be allocated precisely because most of a bank’s noninterest expenses are shared by two or more units. The switch to supermarket branches and kiosks is a development that could help maintain or even increase the availability of banking services in these communities. Supermarket branches reduce a bank’s fixed and operating costs substantially. A bank may therefore be willing to operate in-store branches and kiosks in those areas that could not sustain a traditional branch. A potential stumbling block, however, is the shortage of large supermarkets in urban areas. Hence, in deciding whether to offer tax incentives, zoning variances, or other inducements to attract large supermarkets to lowand moderate-income areas, local governments may also wish to consider the opportunities that these large retail outlets offer to increase the availability of banking services. 6. Most estimates of the total expenses of branch operations fall in the range of 200 to 300 basis points. The variance seems to be attributable to differences in operational efficiency and cost-accounting methodology. It is unclear whether each estimate captures all direct and indirect expenses attributable to branch operations. 7. The public disclosure of results by line of business in 1995 annual reports indicates that, among the few banks that specifically break them out, branch-based operations are not particularly profitable, in some cases earning a lower return on equity than other major segments such as corporate banking and national consumer finance. 8. The calculation of the HHI involves three steps: obtaining the percentage shares of total deposits in the market held by each bank (or bank holding company), squaring these numbers, and summing the results. For example, a market served by five banks, each with a 20 percent share of total deposits, would have an HHI value of (5) x (20)2, or 2000. The Federal Reserve reviews the competitive effects of proposed mergers that produce a value of the HHI greater than 1800 or increase the HHI by more than 200 points. See Jayaratne and Hall (1996) for more information on the HHI. Conclusion In restructuring their retail operations, many large commercial banks are adopting a promising new design for a branch office: the supermarket, or in-store, branch. By opening scaled-down branches in retail outlets, 5 FRBNY CURRENT ISSUES IN ECONOMICS AND FINANCE References American Banker. 1996. “B of A Blitz to Put 50 Banks in Chicago Groceries.” July 26. Jayaratne, Jith, and Christine Hall. 1996. “Consolidation and Competition in Second District Banking Markets.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Current Issues in Economics and Finance 2, no. 8 (July). Neill, Daniel S., and John P. Danforth. 1996. “Bank Merger Impact on Small Business Services Is Changing.” Banking Policy Report 15, no. 8 (April 15). Orlow, Daniel K., Lawrence J. Radecki, and John Wenninger. 1996. “Ongoing Restructuring of Retail Banking.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Research Paper no. 9634. People’s Bank. 1996. 1995 Annual Report. About the Authors Lawrence J. Radecki is an assistant vice president in the Banking Studies Function of the Research and Market Analysis Group; John Wenninger is an assistant vice president in the Group’s Payments Studies Function; Daniel K. Orlow, formerly a financial analyst in the Payments Studies Function, is now a financial analyst in the Markets Group. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Recent Current Issues Date Vol./No. Title Author(s) 4/96 2/5 1996 Job Outlook: The New York–New Jersey Region Orr, Rosen 5/96 2/6 Understanding Aggregate Default Rates of High Yield Bonds Helwege, Kleiman 6/96 2/7 The Yield Curve as a Predictor of U.S. Recessions Estrella, Mishkin 7/96 2/8 Consolidation and Competition in Second District Banking Markets Jayaratne, Hall 8/96 2/9 Securitizing Property Catastrophe Risk Borden, Sarkar 9/96 2/10 Repo Rate Patterns for New Treasury Notes Keane 10/96 2/11 Has the Stock Market Grown More Volatile? Laster, Cole 11/96 2/12 New York State’s Merchandise Export Gap Howe, Leary Readers interested in obtaining copies of Current Issues in Economics and Finance through the Internet can visit our site on the World Wide Web (http://www.ny.frb.org). From the Bank’s research publications page, you can view, download, and print any edition in the Current Issues series, as well as articles from the Economic Policy Review. You can also view abstracts for Staff Reports and Research Papers and order the full-length, hard-copy versions of them electronically. Current Issues in Economics and Finance is published by the Research and Market Analysis Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Dorothy Meadow Sobol is the editor. Editorial Staff: Valerie LaPorte, Mike De Mott, Elizabeth Miranda Production: Graphics and Publications Staff Subscriptions to Current Issues are free. Write to the Public Information Department, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 33 Liberty Street, New York, N.Y. 10045-0001, or call 212-720-6134. Back issues are also available.