NCCN 500 - Stakeholders

advertisement

NCCN 500

This is the non-confidential

version. Confidential information

and data have been redacted.

Redactions are indicated by []

1 August 2008

Contents

Section

1

2

Page

Glossary of terms

1

Executive summary

8

Market definition and dominance

BT’s conduct

8

9

Background

NTS

12

NTS hosting and revenue sharing

The NTS regulatory regime

NTS wholesale charging arrangements

NTS call termination

The NTS Calculator

Transit

3

4

12

14

15

16

16

17

17

NTS regulatory policy

NCCN 500

NCCN 651

The first complaint

The NTS call termination market review

18

19

20

21

21

Ofcom’s investigation

23

The complaint

The investigation

Period of investigation

Evidence gathered

Evidence gathered from BT

Evidence gathered from C&W

Evidence gathered from third parties

The draft decision

Evidence gathered following the draft decision

23

25

25

25

25

28

30

30

31

The relevant market

34

Summary

Identifying markets

34

34

Identifying the relevant product market

Identifying the relevant geographic market

Markets relevant to this investigation

Introduction

NTS markets

Downstream markets: retail NTS calls

Upstream wholesale markets

The relevant market

Introduction

Analysis of NTS call termination/hosting as a two-sided market

NTS call termination/hosting market: analysis

Termination/hosting of unmetered internet traffic and calls to directory enquiries fall

outside the relevant market

Conclusion

Relevant geographic market

Conclusion

Responses to draft decision: Ofcom’s approach to market definition

35

36

37

37

37

40

41

43

43

44

51

60

61

61

62

62

BT

C&W

CPW

Thus

Ofcom comments on responses

Application of the SSNIP test

Ofcom’s analysis of the market as a single market, rather than as two separate

markets

5

66

67

67

BT’s position in the relevant market

74

Introduction

Market shares

74

74

Volume market shares

Conclusion on BT’s market share

Barriers to entry and expansion

Barriers to entry

Barriers to expansion

Constraints on BT from competing suppliers of NTS termination/hosting

Special cases: BT-originated traffic

Special cases: traffic transited by BT

Initial conclusion: traffic originated and transited by BT

Constraints that apply in the case of BT-terminated traffic

Constraints on BT from customers

OCP responses to a price increase by BT

Absorbing increased costs

Refusing to carry BT-terminated traffic

Pass price increase on to own retail callers

Effect if price increase were passed on

Observed behaviour following termination price increases

Conclusion on pass-through

Evidence on profit effect of NCCN 500

Constraints imposed by NTS service providers

Conclusion on the constraints faced by BT

NCCN 651

6

62

64

65

65

75

77

77

77

79

80

82

83

85

85

85

85

87

88

91

92

94

96

96

97

98

99

Responses to draft decision: Ofcom’s provisional conclusions on dominance

100

The conduct

105

Introduction

Alleged margin squeeze

Alleged margin squeeze in retail markets

105

106

106

Alleged margin squeeze in retail markets: the allegation

Alleged margin squeeze in retail markets: legal and economic framework

Alleged margin squeeze in retail markets: analysis

Alleged margin squeeze in retail markets: scope of margin squeeze test

Alleged margin squeeze in retail markets: methodological issues

Conclusion on retail margin squeeze

Responses to draft decision: retail margin squeeze

BT

C&W

Thus

Ofcom comments on responses to the draft decision

Possible margin squeeze in NTS hosting

Introduction

Hosting margin squeeze in a two-sided market

Definition of the hosting margin

Range of services

Cost of capital

Cost standard

106

107

111

112

116

129

129

129

129

130

131

134

134

134

135

135

136

136

1

Relevant time period

Data and results

Revenues

Costs

Summary of results

Responses to draft decision: hosting margin squeeze

BT

C&W

Ofcom comments on responses

Alleged discrimination

Alleged discrimination: the allegation

Alleged discrimination: legal framework

Alleged discrimination: analysis

Responses to draft decision: Ofcom’s analysis of alleged discrimination

C&W

Thus

Ofcom comments on responses

Alleged excessive pricing

Alleged excessive pricing: the allegation

Alleged excessive pricing: legal and economic framework

Alleged excessive pricing: assessing BT’s prices compared to costs

FAC profitability analysis: introduction

FAC profitability analysis: source of information

FAC profitability analysis: basis of preparation

FAC profitability analysis: results

FAC profitability analysis: summary of results

Alleged excessive pricing: profitability analysis based on SAC

SAC profitability analysis: methodology

Modelling the hypothetical single product firm’s network costs

Modelling the hypothetical single product firm’s non-network costs

Results

Model input analysis

Alleged excessive pricing: conclusion

Were BT’s prices excessive compared to costs?

Were the prices notified in NCCN 500 unfair in themselves or when compared with

competing products?

Conclusion on excessive pricing

Responses to draft decision: excessive pricing

C&W

CPW

Thus

Ofcom comments on responses

Other allegations made by C&W

NCCN 500 increased C&W’s costs of providing a competing service

NCCN 500 increased BT’s market power

NCCN 500 was part of a concerted strategy to dilute competition

Responses to draft decision: impact on BT’s competitors and BT’s intentions

C&W

CPW

Thus

Virgin Media

Ofcom comments on responses

Conclusion

Margin squeeze

Discrimination

Excessive pricing

Retail calls to NTS numbers

FAC profitability analysis: cost basis for wholesale services

FAC profitability analysis: stages of analysis

2

136

137

137

138

141

141

141

141

142

144

144

145

147

151

151

152

153

155

155

155

160

163

164

164

165

168

169

169

170

179

181

184

185

186

187

190

191

191

193

194

195

199

199

200

201

204

204

206

206

207

207

209

209

210

210

216

236

237

FAC profitability analysis: differences between voice and data

Annex

238

Page

1

NCCN 500 ................................................................................................... 211

2

NCCN 651 ................................................................................................... 213

3

Calculation of critical elasticity for calls to 0845 numbers .................... 215

4

Related markets......................................................................................... 216

Other wholesale calls markets ................................................................................ 220

5

ROCE and ROS .......................................................................................... 224

6

The importance of capital employed in BT’s retail services.................. 226

7

Alleged margin squeeze in call origination: data sources and

calculations................................................................................................ 229

8

Alleged margin squeeze in call origination: sensitivity analysis .......... 231

NTS calls account for a larger proportion of all calls ............................................... 231

Sensitivity: business customers generate same proportion of data calls as

voice calls.................................................................................................... 232

Sensitivity: C&W time of day weights ...................................................................... 234

9

FAC profitability analysis: basis of preparation ..................................... 236

3

Glossary of terms

Act: the Competition Act 1998.

Article 82: Article 82 of the EC Treaty, which provides that “any abuse by one or

more undertakings of a dominant position within the common market or in a

substantial part of it shall be prohibited as incompatible with the common market in

so far as it may affect trade between Member States”.

Average total cost (“ATC”): average total cost is the sum of fixed costs (costs that

do not vary with changes in output) and variable costs (costs that vary with changes

in output). Average total cost is total cost divided by output.

Average variable cost (“AVC”): variable costs are costs that vary with changes in

output, e.g. materials, energy, direct labour, supervision, repair and maintenance and

royalties. Average variable cost is variable cost divided by output.

BT: BT Group plc and its subsidiary undertakings.

BT Retail: a retail business of BT providing a range of retail services to residential,

business and corporate customers.

Commission: the European Commission.

Communications provider: a person who provides an electronic communications

network or an electronic communications service, as defined in the General

Conditions of Entitlement.

CPS: carrier pre-selection, a mechanism that enables a customer to transfer some or

all of his calls to an alternative communications provider, while retaining his existing

telephone line, without having to dial additional codes or use special equipment.

CPSO: carrier pre-selection operator, a communications provider that interconnects

with BT’s network and that has put in place the necessary arrangements to allow

customers who have a BT line to subscribe to CPS services that it provides.

Chapter II Prohibition: Section 18 of the Competition Act 1998, which provides that

“any conduct on the part of one or more undertakings which amounts to the abuse of

a dominant position in a market is prohibited if it may affect trade within the United

Kingdom”.

CAT: the Competition Appeal Tribunal, which was created by Section 12 and

Schedule 2 to the Enterprise Act 2002 which came into force on 1 April 2003.

CFI: the European Court of First Instance.

Dial-up internet access: internet access that uses a dial-up connection over an

analogue or ISDN (Integrated Services Digital Network) telephone line.

DLE: digital local exchange, the telephone exchange to which customers are directly

connected, often via a remote concentrator unit.

DQ: directory enquiries.

4

Discounted cashflow (“DCF”): an approach to measuring profitability under which

future costs and revenues are expressed as a present value by applying an

appropriate discount rate.

Enterprise Act: the Enterprise Act 2002.

ECJ: the European Court of Justice.

FAC: fully allocated cost, an accounting method for attributing all the costs of the

company to defined activities such as products and services. Typically this method is

guided by the principle of cost causation.

FRIACO: flat rate internet access call origination, a wholesale product purchased by

TCPs from BT that acts as an input for retail flat-rate dial-up internet access.

Freephone: Freephone numbers are numbers starting 0800 and 0808 which are

generally free to call from BT lines.

Geographic numbers: geographic numbers are telephone numbers that relate to a

particular geographic location, indicated by a geographic area code starting 01 or 02.

ISP: internet service provider, a company that provides business and residential

customers with access to the internet and other related services.

IP: Internet Protocol, the packet data protocol used for routing and carriage of

messages across the internet and similar networks.

IP network: a network that uses IP, for example the internet.

Inter-tandem transit: an interconnection service that involves the use of two tandem

switches and one inter-tandem transmission link.

Long run incremental cost (“LRIC”): the costs caused by the provision of a defined

increment of output, taking a long run perspective, assuming that some output is

already produced. The ‘long run’ means the time horizon over which all costs

(including capital investment) are variable.

Net present value (“NPV”): the result from a DCF analysis that discounts costs and

revenues using the applicable discount rate and sums these together.

NCCN: Network Charge Change Notice, the mechanism by which BT notifies other

communications providers of changes to its charges, including charges for the

termination of calls to NTS numbers.

National Telephone Numbering Plan (“NTNP”): a document published by Ofcom

that provides details of all telephone numbers administered by Ofcom and specifies

restrictions on the adoption or use of numbers that Ofcom considers appropriate for

each range.

Non-geographic numbers: a non-geographic number means any telephone number

that is not a geographic number.

NTS: Number Translation Services, telephone services using prefixes listed in the

NTNP as “Special Services”, which start with 08 and 09.

5

NTS call origination condition: a requirement imposed on BT that requires it to

originate and retail calls to NTS numbers on behalf of other TCPs, which was

imposed by Oftel (the agency responsible for regulation of telecommunications in the

UK before the establishment of Ofcom) in 2003 after it concluded that BT had SMP in

the wholesale call origination market.

NTS call termination market review consultation: Ofcom’s consultation document

NTS call termination market review, published 22 October 2004.

NTS retail uplift: part of the cost incurred by BT in originating an NTS call is the cost

of retailing, which BT is allowed to recover under the conditions of the NTS call

origination condition.

NTS service provider: a provider of voice or data services to callers who dial NTS

numbers.

OCP: originating communications provider, the communications provider that

owns/operates the network where a call begins.

Ofcom: the Office of Communications.

OFT: the Office of Fair Trading.

POC: point of connection, the point at which another communications provider’s

network interconnects with that of BT, often at a Digital Main Switching Unit

(“DMSU”).

PRS: premium rate services, services supplied over premium rate (09) numbers,

used mainly to provide access to competitions, TV voting lines, scratchcards, adult

entertainment, chatlines and some post-sales services such as technical support.

PSTN: the public switched telephone network.

Relevant period: 1 May 2004 to 1 January 2006, the period for which the prices

notified in NCCN 500 were in force

Return on capital employed (“ROCE”): the ratio of accounting profit to capital

employed. The measure of capital employed can be either Historic Cost Accounting

(“HCA”) or Current Cost Accounting (“CCA”).

Return on sales (“ROS”): the ratio of operating profit to sales.

Service provider: a provider of electronic communications services to third parties

whether over its own network or otherwise.

SAC: standalone cost, the cost of providing a particular service, which is the sum of

the incremental cost of the service (i.e. is the cost of producing a specified additional

product, service or increment of output over a specified time period) plus all of the

costs which are common between that service and other services.

6

SMP: significant market power, as defined in Article 14(2) of the Framework

Directive, which states that: “an undertaking shall be deemed to have significant

market power if, either individually or jointly with others, it enjoys a position

equivalent to dominance, that is to say a position of economic strength affording it the

power to behave to an appreciable extent independently of competitors, customers

and ultimately consumers.”

Single transit: interconnection service that involves the use of a single tandem

switch.

TCP: terminating communications provider, the communications provider that

owns/operates the network where a call ends.

Weighted average cost of capital (“WACC”): a company's WACC measures the

rate of return that a firm needs to earn in order to reward its investors. It is an

average representing the expected return on all of its securities, including both equity

and debt.

WLR: wholesale line rental, a mechanism that enables alternative suppliers to rent

access lines on wholesale terms from BT, as mandated by Ofcom’s Review of the

fixed narrowband wholesale exchange line, call origination, conveyance and transit

markets, and to resell the access lines to end consumers.

7

Section 1

1 Executive summary

1.1

The Office of Communications (“Ofcom”) has concluded that BT Group plc (“BT”) has

not infringed section 18 (“the Chapter II prohibition”) of the Competition Act 1998

(“the Act”) or Article 82 of the EC Treaty (“Article 82”) in relation to its prices for

Number Translation Services (“NTS”) call termination between 1 May 2004 and 1

January 2006, as notified in Network Charge Change Notice 500 (“NCCN 500”)

issued on 1 April 2004.

1.2

Ofcom opened an investigation on 8 April 2005 in response to a complaint submitted

to Ofcom on 15 March 2005 by Cable & Wireless Communications plc (“C&W”)

alleging that BT was dominant in a number of relevant markets including the market

for NTS call termination, and that BT had abused its dominant position in relation to

the price increases for NTS call termination on certain number ranges, as notified in

NCCN 500.1

1.3

Ofcom reached a provisional conclusion that the available evidence did not support

the view that BT’s conduct over the relevant period infringed the Chapter II

prohibition and/or Article 82 and that there were therefore no grounds for action. On

23 July 2007 Ofcom provided a non-confidential version of its provisional decision to

BT, C&W and four other parties supporting C&W’s complaint and invited them to

submit written responses on its provisional decision.

1.4

After considering respondents’ comments on its provisional decision, Ofcom has

reached the conclusion that the available evidence does not support the view that

BT’s conduct over the relevant period infringed the Chapter II prohibition and/or

Article 82 and that there are therefore no grounds for action.

Market definition and dominance

1.5

Ofcom has concluded that the relevant market for the consideration of C&W’s

allegations is the market for the termination/hosting of NTS calls on all number

ranges, by all terminating communications providers (“TCPs”) in the UK. Ofcom’s

reasoning on the relevant market is set out at Section 4 below.

1.6

BT’s share of the NTS call termination/hosting market, based on total volumes, was

below a level that would typically be associated with a position of dominance in the

relevant market. However, Ofcom found that BT is able to act independently of other

TCPs, its competitors, its customers and ultimately of consumers due to the

particular structure and features of the market.

1.7

Ofcom found that BT was able to introduce price increases for NTS call termination

without its TCP competitors, or its originating communications provider (“OCP”) and

NTS service provider customers being able to constrain its pricing behaviour.

1

The complaint that generated this investigation was submitted by Energis Communications Ltd

(“Energis”, UK company number 02630471). On 16 August 2005, Cable & Wireless plc (“C&W”, UK

company number 00238525) announced an agreement to acquire Energis. On 25 October 2005, the

OFT announced that it would not refer the acquisition to the Competition Commission. The

complainant is referred to throughout this document as “C&W”, except where it is necessary for clarity

to make a distinction between the two entities that existed prior to C&W’s acquisition of Energis.

8

1.8

1.9

BT’s competitors and customers were unable to constrain BT’s pricing behaviour

because of:

•

BT’s position in retail markets, which meant that OCPs were reluctant to pass on

the price increase to their retail customers (which would not in any case have

undermined BT’s ability to increase its NTS call termination charges);

•

BT’s significant market power (“SMP”) in the market for call origination which,

combined with the National Telephone Numbering Plan (“NTNP”) requirements

on retail prices, prevents other TCPs from raising their gross termination charges

on BT-originated calls to NTS numbers;

•

BT’s SMP in the market for single transit, which prevents other TCPs from raising

their gross termination charges on non BT-originated calls to NTS numbers; and

•

the fact that BT would have been able to match or better any outpayment to an

NTS service provider that a competing TCP could have made.

Ofcom has therefore found that BT was dominant in the market for NTS call

termination/hosting in the UK between 1 May 2004 and 31 December 2005, the

period of the investigation. Ofcom’s reasoning on BT’s position in the relevant market

is set out at Section 5 below.

BT’s conduct

1.10

C&W alleged that the price increases notified in NCCN 500:

•

imposed a margin squeeze on C&W;

•

discriminated in favour of BT and against C&W on price;

•

were excessive;

•

increased C&W’s costs of providing a competing service or forced it to provide an

inferior service to that of BT;

•

increased BT's market power in the NTS call origination and NTS call termination

markets; and

•

formed part of a concerted strategy to dilute competition.

1.11

Before finding an infringement of Article 82 and/or the Chapter II prohibition, Ofcom

must satisfy itself on the evidence that an infringement is more likely than not to have

occurred.2 The undertaking being investigated is entitled to the presumption of

innocence and to any reasonable doubt that there may be. Ofcom must therefore

proceed on the basis of an analysis that is robust and soundly based.3

1.12

Ofcom’s analysis of BT’s conduct is set out at Section 6 below. In summary,

beginning with the question of an alleged margin squeeze, Ofcom analysed whether

an operator as efficient as BT would be able to compete in the relevant downstream

markets identified in the investigation, under the cost constraints imposed by NCCN

2

3

Napp Pharmaceutical Holdings Ltd v Director General of Fair Trading [2002] CAT 1, paragraph 109.

JJB Sports plc v OFT [2004] CAT 17.

9

500. Ofcom also considered a stricter test using the costs of a reasonably efficient

competitor and BT also passed this stricter test.4

1.13

Ofcom found that BT earned high margins across all calls (even discounting all the

returns associated with local calls), and that, had NCCN 500 applied to all calls

originated by BT, the impact on BT’s margin across the relevant product set would

have been insufficient to lead to a margin squeeze.

1.14

In addition, Ofcom carried out an analysis of whether the additional revenue that BT

gained from NCCN 500 enabled it to fund higher payments to its NTS service

providers, leading to a margin squeeze in NTS hosting. Ofcom found that BT’s

conduct did not lead to a margin squeeze in NTS hosting.

1.15

On the question of discrimination by BT, in launching this investigation Ofcom was

concerned by public statements made by BT which appeared to indicate that BT had

charged different rates to other OCPs than to BT. BT also appeared to consider

internally that it had “discriminated” in its charge to other OCPs. Ofcom investigated

BT’s regulatory costing systems to assess the actual internal transfer charge paid by

BT. There was not robust evidence of a “hard” charge to BT that was different from

the charge that applied to BT’s competitors. Ofcom considered whether BT’s charges

for NTS call termination, as notified in NCCN 500, might amount to “applying

dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby

placing them at a competitive disadvantage”.5

1.16

Ofcom considers that in the circumstances of NCCN 500 the relevant test for

determining whether BT was discriminating in favour of itself in an anti-competitive

manner is whether BT would have been able to make a profit had it paid the charges

notified in NCCN 500, taking into account profits earned on all the relevant services,

i.e. whether BT’s conduct led to the operation of a margin squeeze on other OCPs.

As already noted, Ofcom found insufficient evidence to support a finding of a margin

squeeze. Notwithstanding BT’s statements on NCCN 500, given the results of the

margin squeeze tests, Ofcom did not find compelling evidence to demonstrate that

BT had discriminated between itself and other OCPs putting them at a competitive

disadvantage.

1.17

Ofcom did not find any evidence that BT’s conduct led to a distortion of competition,

and found limited evidence of any adverse effect on consumers. Ofcom concluded

that BT’s intention was to increase revenue and draw Ofcom’s attention to anomalies

in current NTS regulation, not to reduce competition.

1.18

Ofcom considered that it would have needed compelling evidence of excessive

pricing, according to the tests set out in the case law. Ofcom considered these tests,

to the extent that they were relevant in this case, offered conflicting evidence as to

whether the prices notified in NCCN 500 were excessive. Ofcom found that BT’s

prices appeared to be significantly above its fully allocated cost (“FAC”), but below

another relevant measure of cost, standalone cost (“SAC”).

4

Ofcom notes the tests set out by the Court of Appeal in Albion (Dwr Cymru Cyfyngedig and Albion

Water Limited and Water Services Regulation Authority [2008] EWCA Civ 536) and by the CFI in

Deutsche Telekom (Case T-271/03 Deutsche Telekom v Commission Judgement of CFI 10 April

2008). See paragraph 6.23 et seq below.

5

Article 82 2(c).

10

1.19

Overall, in the circumstances of this case and in light of the need for compelling

evidence, there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate to the required standard of

proof that BT’s conduct constituted an abuse of its dominant position.

11

Section 2

2 Background

NTS

2.1

NTS numbers are those number ranges listed in the NTNP as “Special Services”

numbers.6 NTS numbers start with 08 or 09.7

2.2

An NTS number does not relate to a specific geographic location, but to a particular

service. The NTS number dialled by a caller is ‘translated’ by the network to a

geographic number to deliver the call to its destination.

2.3

The NTNP lists the numbers available for allocation and also specifies such

restrictions on the adoption or use of numbers that Ofcom considers appropriate for

each range. The designations for NTS numbers are summarised in Table 1 below. In

the case of NTS numbers the designations specify retail prices for calls from BT

lines.8

2.4

NTS numbers are used to provide access to a range of voice and data services.

Research undertaken by Ofcom as part of its review of NTS regulatory policy (see

paragraph 2.34 et seq below) suggested that different NTS number ranges are, to

some extent, associated with different types of services:

6

•

Freephone numbers (0800 and 0808) are mainly used to access private sector

voice services such as sales lines and helplines; and telephony services provided

by two-stage indirect access service providers;

•

0844/0843 and 0845 numbers are used extensively for metered dial-up internet

access (predominantly using 0845 numbers), and also support a wide range of

other services, including pre- and post-sales enquiry lines, public sector services,

transaction services and information services;

•

0870 and 0871/0872/0873 numbers are mainly used to provide access to preand post-sales enquiry lines, some public sector services and international

telephony services provided by resellers; and

•

Premium Rate (09) numbers are used mainly to access competitions, TV voting

lines, scratchcards, adult entertainment, chatlines and some post-sales services

such as technical support.9

The current version of the NTNP was published on 17 June 2008 at:

http://www.ofcom.org.uk/telecoms/ioi/numbers/numplan170608.pdf.

7

NTS also includes calls to the legacy 0500 (Freephone) and 0345 (local rate) ranges, which are not

available for new allocations and are no longer listed in the NTNP. NTS does not include calls to 0844

04 numbers for Surftime internet access or calls to 0808 99 numbers for unmetered dial-up internet

access based on FRIACO (flat rate internet access call origination).

8

In the consultation Changes to 0870, published on 2 May 2008 (see

http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/0870calls/0870condoc.pdf) Ofcom has proposed changes

to the charges that communications providers can make for calls to 0870 numbers. The designations

set out in Table 1 below and referred to elsewhere in this document are those that applied during the

period under investigation.

9

See Number Translation Services: Options for the future, 22 October 2004, published at:

http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/ntsoptions/nts_future/nts_future_op.pdf.

12

2.5

0820 numbers are reserved for Schools Internet Caller, a legacy service for schools

that enables them to make free dial-up calls to the internet during school hours,

reverting to normal tariffs in the evenings and at weekends (see footnote 243).

Table 1: The NTS number ranges

Range

Designation

0800 and 0808

Free to caller (unless charges are notified to the caller at the start of the

call)

0820

Schools internet

0844/0843

Special Services basic rate: charged at up to and including 5p per minute

or per call for BT customers, set by TCP including VAT (the price charged

by other OCPs may vary)

0845

Special Services basic rate: charged (before discounts and call packages)

at BT’s Standard Local Call Retail Price for BT customers including VAT

(the price charged by other OCPs may vary)

0870

Special Services higher rate: charged (before discounts and call

packages) at BT’s Standard National Call Retail Price for BT customers

including VAT (the price charged by other OCPs may vary)

Special Services higher rate: up to and including 10p per minute or per

0871/0872/0873 call for BT customers including VAT (the price charged by other OCPs

may vary)

Special Services at a Premium Rate: charged to BT customers

090 and 091

•

Generally at more than 10p per minute, up to and including £1.50 per

minute including VAT; or

•

at more than 10p per call, up to and including £1.50 per call including

VAT.

Sexual Entertainment Services at a Premium Rate: charged to BT

customers

098

•

generally at more than 10p per minute, up to and including £1.50 per

minute including VAT; or

•

at more than 10p per call, up to and including £1.50 per call including

VAT.

Source: NTNP.

2.6

There may be several communications providers involved in conveying an NTS call

from the caller to the organisation or individual receiving the call (“the NTS service

provider”), including an OCP, on whose network the call originates, and a TCP, on

13

whose network the NTS number terminates.10 The OCP and the TCP may be the

same for some calls. A third communications provider (a “transit” provider) may carry

the call between the OCP and the TCP.

2.7

These relationships are shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: Parties involved in an NTS call

retail price

OCP

Transit CP

(if used)

revenue

share

payment

termination

charge

TCP

NTS service

provider

NTS hosting and revenue sharing

2.8

The regulatory framework for NTS enables the TCP to share the revenue from calls

to NTS numbers with NTS service providers. NTS thereby acts as a micro-payment

mechanism for the various services that can be accessed via 08 and 09 numbers.

The caller pays the OCP for the call. The OCP passes on a terminating payment to

the TCP, who is then able (subject to commercial viability) to share some of this

revenue with the NTS service provider.

2.9

The TCP has two distinct roles in this arrangement. First, it provides call termination

to the OCP. Second, it provides various services to NTS service providers, which we

refer to collectively as “NTS hosting” (see also paragraph 4.28 below).

2.10

NTS hosting includes the payment of revenue shares. It also includes the provision of

a range of value added services.

2.11

NTS service providers vary hugely in their scale and in the services that they offer to

callers, and therefore have very different NTS hosting requirements. Some voice

services may consist of simple number translation and routing to a particular

geographic number (e.g. an 0845 number allocated to a small organisation or an

individual, at a single geographic number). At the other end of the scale, the

customer may be a large national organisation (for example a retailer, high street

bank or government department), receiving very large volumes of calls, with call

centres at multiple locations, and will require a wider range of call routing and call

management services.

2.12

NTS hosting may therefore include a range of value added services, including:

a) conditional call routing to one or more destination numbers based on static or

dynamic parameters such as:

o the caller’s telephone number or location;

10

For the purposes of this decision, Ofcom is using the definition of “communications provider” in

section 405 of the Communications Act 2003, which is “a person who provides an electronic

communications network or an electronic communications service”. Section 32 of the

Communications Act 2003 defines an electronic communications network as “(a) a transmission

system for the conveyance, by the use of electrical, magnetic or electro-magnetic energy, of signals of

any description; and (b) such of the following as are used, by the person providing the system and in

associated with it, for the conveyance of the signals – (i) apparatus comprised in the system; (ii)

apparatus used for the switching or routing of the signals; and (iii) software and stored data.”

14

o time or date;

o routing plans defined by the NTS service provider;

o call distribution to multiple sites based on static rules, or call centre load; or

o customer keypad selections or voice commands;

b) recorded announcements;

c) call management functionality such as live or historical traffic information and

dynamic customer control of call routing parameters.

2.13

In the case of data services, NTS hosting may consist of termination of calls on a

suitable modem, user authentication, internet protocol (“IP” – see Glossary) traffic

aggregation and management, and IP traffic conveyance.

The NTS regulatory regime

2.14

The NTS regulatory regime is based on two formal regulatory instruments, which are

described in the following paragraphs. One of these (the NTS call origination

condition) applies to BT only. The other (the NTNP) applies to all communications

providers.

2.15

The current NTS regulatory regime dates back to 1996. The framework originally put

in place by Oftel aimed to encourage the provision of services over the telephone.11 It

did this by enabling TCPs to receive the profit from calls to NTS numbers and share it

with NTS service providers, who could in turn use that revenue share to fund new

and innovative services.

2.16

This model, and the key elements of the supporting policy, were retained following

the introduction of the new regulatory regime for electronic communications networks

and services that came into force on 25 July 2003.

2.17

Under the new regime, Oftel carried out a series of market reviews, one of which

covered the wholesale market for call origination.12 As a result of this review, Oftel

concluded that BT has SMP in the wholesale call origination market and imposed a

number of SMP conditions on BT, including a requirement to originate and retail calls

to NTS numbers on behalf of other TCPs known as the “NTS call origination

condition”.13

2.18

The NTS call origination condition allows BT to deduct the costs it incurs in

originating the call, retailing the call (the “NTS Retail Uplift”) and making provision for

bad debt for Premium Rate Services (“PRS”) calls (over and above the amount

already allowed for by the NTS Retail Uplift) before passing the remainder of the

retail charge (the amount that the caller pays) on to the relevant TCP, which can use

it to fund revenue share payments to its NTS service providers. BT’s call origination

11

Oftel (the Office of Telecommunications) was the authority responsible for the regulation of

telecommunications in the UK prior to the creation of Ofcom at the end of 2003.

12

Review of the fixed narrowband wholesale exchange line, call origination, conveyance and transit

markets: Identification and analysis of markets, determination of market power and the setting of SMP

conditions. Final Explanatory Statement and Notification, 28 November 2003, published at:

www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/narrowband_mkt_rvw/nwe/.

13

Review of the fixed narrowband wholesale exchange line, call origination, conveyance and transit

markets, statement of 28 November 2003 (see footnote 12), SMP Services Condition AA11.

15

charges and NTS Retail Uplift charge are regulated by a charge control – another of

the remedies imposed by Ofcom to address BT’s SMP in the wholesale call

origination market (see previous paragraph).14 The other deductions that BT makes

are also regulated.15

2.19

The second element of the NTS regulatory regime is the NTNP. As set out in Table 1

above, the NTNP specifies what the various different NTS number ranges can be

used for. Communications providers to which Ofcom has allocated NTS numbers

assume a responsibility to ensure that those numbers are used in accordance with

the designations given in the NTNP.

NTS wholesale charging arrangements

2.20

For every end-to-end NTS call, there may be a number of transactions between the

different parties involved, as set out in Figure 1 above.

2.21

The caller is billed for the call by his OCP, which retains a proportion of the retail call

charge to cover the cost of originating the call and providing retail services (such as

billing and customer service) to the customer (although only when BT is the OCP is

the amount retained for origination explicitly cost-based). The OCP passes the

residual amount to the TCP as an NTS call termination payment. Finally, the TCP

may have a revenue sharing arrangement with the NTS service provider. Where the

call is transited by a third party, there is an additional transaction in the chain: the

transit provider retains a proportion of the retail price for the provision of the transit

service before handing the call on to the TCP for completion (see paragraph 2.31 et

seq below).

NTS call termination

2.22

BT’s charges for the termination of calls to NTS numbers are not regulated. Nor are

those of any other TCP.

2.23

Non-BT TCPs’ charges for the termination of calls to NTS numbers are, however,

determined to a large extent by regulation. As set out above, the maximum retail

price of a call by a BT customer to an NTS number is subject to the limits set out in

the designations in the NTNP. The amount in pence per minute (“ppm”) that BT can

retain out of the retail charge is limited by the NTS call origination condition and the

charge controls as discussed in paragraph 2.18 above. The amount that is passed

through to the TCP (the termination charge) is therefore equivalent to the retail

charge, minus BT’s retention, minus any payment to a transit provider. For a further

discussion of TCPs’ ability to influence the level of their charges for the termination of

NTS calls, see Section 5 below.

2.24

Similarly where a TCP other than BT terminates calls that have originated on another

OCP’s network and transited via BT, BT pays the same termination charge as if the

call originated on BT’s network. This is because BT’s wholesale billing systems are

unable to take account of other OCPs’ retail prices or originating retentions and

therefore can only pay the same termination charge for all calls to any one TCP.

14

Review of BT’s network charge controls: Explanatory Statement and Notification of decisions on

BT’s SMP status and charge controls in narrowband wholesale markets, 18 August 2005, published

at: www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/charge/statement/.

15

BT’s charges for NTS Retail Uplift and the provision for PRS bad debt are set out in Charges

between Communications Providers: Number Translation Services Retail Uplift charge control and

Premium Rate Services bad debt surcharge, 28 September 2005, published at:

www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/NTSfin/statement_nts_uplift/.

16

2.25

BT’s charges for the termination of NTS calls originated by other OCPs, on the other

hand, are not influenced by regulation in the wholesale call origination market. No

OCP other than BT is subject to regulation of charges for originating NTS calls, so

the proportion of the retail price that is passed through to BT (i.e. BT’s termination

charge) is equivalent to the unregulated retail price of the call, minus the OCP’s

retention, minus any payment to a transit provider (but see discussion at paragraph

5.56 et seq below).

2.26

Before it issued NCCN 500 (see paragraph 2.41 et seq below), BT behaved as

though its charges for NTS call termination were regulated, in that it applied the same

termination charges for OCP-to-BT calls as its competitors charged for BT-to-TCP

calls (the latter being indirectly set by the combination of the NTNP and regulation on

BT in the wholesale call origination market). NCCN 500 raised BT’s charges for

terminating OCP-to-BT calls above TCPs’ charges for terminating BT-to-TCP calls.

The NTS Calculator

2.27

In order to assist TCPs in calculating their NTS termination charges BT has made

available, on its BT Wholesale website, an online tool called the NTS Calculator.16

This is an extensive Excel spreadsheet which enables TCPs to input their own call

routing parameters and to calculate how much they can expect to receive for

terminating any 08 or 09 call. The NTS Calculator is maintained both as an up-todate tool, with the latest wholesale network charges, discounts, NTS Retail Uplift and

PRS bad debt surcharge, and as a historic tool which enables TCPs to assess how

these factors have changed over time and measure the resultant effect on their

termination charges.

2.28

Charges for the termination of calls to NTS numbers differ by number range, by time

of day, and in some cases by call length.

2.29

Calls are classed as either “Daytime”, “Evening” or “Weekend”. “Daytime” calls are

calls made by residential customers between 6am and 6pm, or by business

customers between 8am and 6pm. “Evening” calls are calls made after 6pm and

“Weekend” calls are calls made on Saturday and Sunday.

2.30

During the period under investigation, calls to some NTS number ranges (0845, its

legacy equivalent 0345, and 0820) were classed as either “short” or “long”. “Short”

calls were defined during the period under investigation as calls shorter than the call

duration corresponding to BT’s minimum call charge; “long” calls as calls equal to or

longer than the call duration corresponding to the minimum call charge.17

Transit

2.31

Payment arrangements for transit depend on number range. Where BT acts as

transit provider, the OCP pays for transit for calls to number ranges starting 0844 and

0871, whereas the TCP pays for transit for calls to number ranges starting 0845 and

0870, as shown in Figure 2 below.

16

http://www.btwholesale.com/pages/static/service_and_support/service_support_hub/online_pricing_

hub/cpl_hub/cpl_pricing_hub/number_translation_services.html.

17

As of 1 October 2006, the minimum call charge was replaced with a “call set-up fee” of 3p. As a

result the concept of “short” and “long” NTS calls no longer applies.

17

Figure 2: NTS transit arrangements

D = BT’s discounted retail price

C = BT’s retention

D-C

P

OCP

D-C

BT

T

Originator pays transit (for 0844/0871)

TCP

NTS SP

T

Terminator pays transit (for 0845/0870/PRS)

P = OCP’s retail price

T = BT’s transit charge

2.32

BT’s transit charges are, in some cases, set by regulation. Ofcom has determined

that BT has SMP in the market for single transit (see paragraphs A4.47-A4.49

below).18 As a remedy, BT’s charges for single transit are subject to a charge control.

2.33

Ofcom has determined that no communications provider has SMP in the market for

inter-tandem transit (see paragraphs A4.50-A4.53 below). Communications providers

are free to negotiate charges for inter-tandem transit. However, the incentives to do

so are limited, as explained in paragraph 5.58 et seq below.

NTS regulatory policy

2.34

Since its inception, Ofcom has conducted a major review of NTS regulatory policy

and implemented a number of changes to the NTS regulatory regime.

2.35

On 22 October 2004 Ofcom published the consultation document, Number

translation services: options for the future, which set out a number of options for

future regulation of NTS (“the NTS consultation”).19 On 28 September 2005 Ofcom

published a further consultation document, Number translation services: a way

forward which proposed a number of detailed changes to the NTS regime.20

2.36

On 19 April 2006 Ofcom published the statement Number translation services: a way

forward (“the NTS statement”) setting out a number of changes to the NTS regulatory

regime, as follows:

•

18

retail prices for calls to 0870 numbers will be linked to prices for geographic calls,

so that OCPs including BT must charge their customers no more for calls to 0870

numbers than for national calls to geographic numbers. OCPs who wish to

charge higher rates for 0870 calls will be required to make a free preannouncement at the beginning of the call, telling the caller how much the call will

cost;

Review of BT’s network charge controls, statement of 18 August 2005 (see footnote 14).

Number translation services: options for the future, 22 October 2004, published at:

http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/ntsoptions/#content.

20

Number translation services: a way forward, 28 September 2005, published at:

http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/nts_forward/nts_way_forward.pdf.

19

18

•

the NTS call origination condition (see paragraph 2.17) will no longer apply to

calls to 0870 numbers;

•

the PRS regulatory framework will be extended to 0871 calls and to all adult PRS

services, regardless of price; and

•

communications providers will be required to give their customers clearer

information about the cost of calling NTS (and PRS) numbers.21

2.37

On the same date, Ofcom published a separate statement entitled Providing citizens

and consumers with improved information about Number Translation Services and

Premium Rate Services, which notified modifications to General Condition 14

requiring communications providers to give their customers clearer information about

the cost of calling NTS and PRS numbers, in line with the last of the changes set out

in the previous paragraph.22 These new requirements came into effect on 19 August

2006.

2.38

The NTS statement explained that the changes to the regulation of the 0870 range

would be implemented 18 months after the publication of Ofcom’s separate

statement on numbering policy, which was published on 27 July 2006 and confirmed,

among other things, a number of policy decisions relating to the NTNP that were

necessary to give effect to the changes to the 0870 regulatory framework set out in

the NTS statement.23

2.39

When Ofcom introduced a requirement for pricing pre-announcements on 070

(Personal Numbers) in an unrelated policy initiative, the pre-announcements

interfered with a small number of social alarm services (typically used by the elderly

and infirm to summon assistance).24 Ofcom also became aware there were a large

number of security alarm services using 0870 numbers that might also be susceptible

to interference from pre-announcements, causing service disruption.

2.40

As a result of these discoveries, Ofcom took extra time to reconsider whether it

should require the use of pricing announcements. Instead of pre-announcements, it

has, at the time of publication, proposed that communications providers wishing to

charge more for 0870 calls than for geographic calls would be subject to new

requirements to display their 0870 charges prominently on price lists and advertising

and promotional materials. The details of Ofcom’s revised proposals are contained in

the consultation document Changes to 0870, published by Ofcom on 2 May 2008.25

NCCN 500

2.41

On 1 April 2004 BT issued NCCN 500, notifying a number of increases to its charges

to third parties (i.e. other OCPs) for the termination of calls to NTS numbers with

effect from 1 May 2004.

21

Number translation services: a way forward, 26 April 2006, published at:

http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/nts_forward/statement/statement.pdf.

22

Providing citizens and consumers with improved information about Number Translation Services

and Premium Rate Services, 19 April 2006, published at:

http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/nts_info/statement/statement.

23

Telephone Numbering: Safeguarding the future of numbers, 27 July 2006, published at:

www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/numberingreview/statement/.

24

See the Ofcom statement Removal of the requirement for pre-call announcements on 070 numbers

at http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/numbering03/070precall/.

25

Changes to 0870: Changes to 0870 calls and modifications to the supporting regulations, 2 May

2008, published at: http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/0870calls/0870condoc.pdf.

19

2.42

The scale of the price rises notified in NCCN 500 differed by number range, by call

duration and by time of day. Price rises ranged between zero (for daytime calls to

0820 numbers) and 37.8% (for long duration evening calls to 0845 numbers). The

most significant rises applied to long duration calls to 0845 numbers.

2.43

NCCN 500 is reproduced in Annex 1.26

2.44

NCCN 500 notified price rises for the termination of calls originated by OCPs. Prior to

NCCN 500, BT had set its charges for NTS call termination at the same level as

other TCPs’ charges for NTS call termination – which other TCPs had set with

reference to BT’s regulated origination and transit charges.

NCCN 651

2.45

On 2 November 2005 BT issued NCCN 651, notifying a number of changes to its

charges to third parties (i.e. other OCPs) for the termination of calls to NTS numbers

with effect from 1 January 2006.

2.46

The effect of NCCN 651 was to bring BT’s charges for NTS call termination back into

line with those of other TCPs, as they had been prior to 1 May 2004. This is shown in

Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: The effect of NCCN 500 and NCCN 651

Termination charge (ppm)

2.0

31 December 2005

1 May 2004

1.8

1.6

1.4

1.2

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0.0

24/07/1998

06/12/1999

19/04/2001

01/09/2002

0845: terminated by other TCP

14/01/2004

28/05/2005

10/10/2006

0845: BT-terminated

Source: NCCN 500, NCCN 651, NTS Calculator

2.47

26

[].27

Ofcom has calculated NCCN 500 price rises with reference to BT’s NTS call termination charges as

at 1 April 2004 for OCP–BT calls using the NTS Calculator. Ofcom notes that BT has relied on NCCN

500 itself (as reproduced at Annex 1 below) when deriving estimated price increases, which suggests

a considerably higher price increase than that implied by the comparison of the charges notified in

NCCN 500 against NTS Calculator generated prices for the period immediately preceding the

introduction of NCCN 500. Ofcom does not consider that the charges listed as “current” in NCCN 500

are a true reflection of the charges paid by OCPs to BT immediately prior to the introduction of NCCN

500. Prior to NCCN 500, Ofcom understands that both OCPs and BT used the NTS Calculator to

determine the level of charges payable for NTS call termination.

20

2.48

The price increases that are the subject of this investigation were therefore in effect

from 1 May 2004 to 31 December 2005 – a period of 20 months.

The first complaint

2.49

On 4 May 2004 C&W submitted to Ofcom a complaint about NCCN 500 (“the first

complaint”).

2.50

In the first complaint, C&W argued that the price increases notified in NCCN 500

constituted an abuse of BT’s dominant position in the market for NTS call

termination, contrary to the Chapter II prohibition, in that they would:

•

impose a margin squeeze on C&W;

•

discriminate in favour of BT and against C&W on price;

•

increase C&W’s costs of providing a competing service or force it to provide an

inferior service to that of BT; and

•

increase BT’s market power in the NTS call origination and NTS call termination

markets.28

2.51

Ofcom considered the first complaint and reached the view that the issues raised

therein would be addressed by Ofcom’s ongoing review of the NTS regulatory regime

(which is described at paragraph 2.34 et seq above). Ofcom therefore decided to

concentrate its resources on completing its review of the NTS regulatory regime,

rather than diverting resources to running a parallel investigation. Ofcom wrote to

C&W on 25 May 2004 informing C&W of this decision.

2.52

Ofcom wrote to C&W again on 7 July 2004 indicating that it would keep the matters

raised in the first complaint under review and that it would not be precluded at some

point in the future from considering a possible breach of the Act or Article 82 from the

date that the alleged breach had occurred.

The NTS call termination market review

2.53

As discussed in the previous section, Ofcom did not open an investigation into the

first complaint, as it considered that the issues raised by C&W in that submission

would be addressed by its ongoing review of the NTS regulatory regime.

2.54

NCCN 500 prompted Ofcom to include, in its ongoing review of the NTS regulatory

regime, a detailed consideration of NTS call termination.

2.55

On 22 October 2004 (the same date that it published the first NTS consultation),

Ofcom published the consultation document NTS call termination market review (“the

NTS call termination market review consultation”).29

2.56

In the NTS call termination market review consultation, Ofcom proposed to identify a

market for NTS call termination in the UK and set out its view that BT has SMP in

that market. Ofcom considered a number of options for action, and indicated that its

27

[].

C&W submission of 4 May 2004, paragraph 1.5.

29

NTS call termination market review, 22 October 2004, published at:

http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/ntsctmr/.

28

21

preferred option was to impose two new SMP conditions on BT, requiring it to provide

network access, and not to exercise undue discrimination in relation to the provision

of network access, in the NTS call termination market.30

2.57

The NTS call termination market review consultation closed on 7 January 2005.

Respondents to the consultation included BT and UKCTA, the trade association of

competitive fixed line carriers in the UK, which represented a number of OCPs and

TCPs with interests in NTS call termination. Non-confidential responses to the

consultation were published on Ofcom’s website.31

2.58

As discussed in Section 3 below, on 7 April 2005 Ofcom opened an investigation into

a further complaint from C&W on 15 March 2005 relating to BT’s charges for NTS

call termination. In order to avoid duplication of analysis, Ofcom decided not to

proceed separately with the market review while the investigation was ongoing, and

has not therefore concluded on the proposals set out in the market review

consultation. Some of the respondents to the draft decision (see paragraphs 3.28 et

seq below) commented that Ofcom should not have suspended the market review

pending the completion of its investigation under the Act. However, Ofcom

considered that the market definition exercise and, to some extent, the dominance

analysis undertaken as part of this investigation would in effect have been duplicated

had Ofcom progressed with the market review and the investigation in parallel. In

Ofcom’s view, this would have represented an inefficient and inappropriate use not

only of Ofcom’s resources, but the resources of the parties to the investigation.

30

31

NTS call termination market review consultation, Section 5.

http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/ntsctmr/resntcctr/.

22

Section 3

3 Ofcom’s investigation

The complaint

3.1

On 15 March 2005 C&W submitted its second complaint to Ofcom about NCCN 500

(“the complaint”).

3.2

In the complaint, C&W alleged that NCCN 500 represented an abuse of BT’s

dominant position in a number of markets, including the market for NTS call

termination.

3.3

C&W submitted that the relevant markets for the purposes of the complaint were the

markets for:

“NTS call origination, NTS call termination, NTS call transit and NTS

service hosting.”32

3.4

C&W submitted that BT holds a dominant position in the market for call origination on

fixed public narrowband networks, noting that Ofcom had found BT to have SMP in

that market (see paragraph 2.17 above).

3.5

C&W submitted that;

“Call origination to NTS number ranges forms a subset of the wider

call origination market and can be distinguished from, and is not

substitutable with, geographic call origination.”33

3.6

C&W submitted in addition that BT has market power in the market for NTS call

termination to services hosted on the BT network.

3.7

C&W submitted that it agreed with Ofcom’s proposals in relation to the NTS call

termination market, as set out in the market review consultation.34

3.8

However, C&W submitted that even if BT were not dominant in the NTS call

termination market, BT’s conduct in issuing NCCN 500 would equally constitute an

abuse of BT’s dominant position in the market for wholesale call origination, since:

“It is only BT’s control over and overwhelming market share in, call

origination that renders BT’s conduct in issuing NCCN 500

profitable.”35

3.9

C&W submitted that NCCN 500 constituted an abuse of BT’s dominant position in

both the market for NTS call termination and the market for wholesale call

origination.36

3.10

C&W alleged that the price increases notified in NCCN 500:

32

C&W submission to Ofcom of 15 March 2005, paragraph 5.5.

C&W submission to Ofcom of 15 March 2005, paragraph 5.10.

34

C&W submission to Ofcom of 15 March 2005, paragraph 5.13.

35

C&W submission to Ofcom of 15 March 2005, paragraph 5.14.

36

C&W submission to Ofcom of 15 March 2005, paragraph 5.16.

33

23

3.11

•

imposed a margin squeeze on C&W;

•

discriminated in favour of BT and against C&W on price;

•

were excessive;

•

increased C&W’s costs of providing a competing service or forced it to provide an

inferior service to that of BT;

•

increased BT's market power in the NTS call origination and NTS call termination

markets; and

•

formed part of a concerted strategy to dilute competition.37

C&W requested:

•

that Ofcom adopt a decision pursuant to section 31 of the 1998 Act that the price

increases notified in NCCN 500 constitute an abuse by BT of its dominant

position;

•

that Ofcom issue directions to BT under section 33 of the 1998 Act requiring it to

take such steps as are necessary to bring those abuses to an end, in particular:

a) that NCCN 500 be withdrawn;

b) that BT be required to reimburse C&W in respect of any payments it had made to

BT based on the higher charges notified in NCCN 500; and

c) that BT be required to charge other OCPs for calls terminated on its network only

in accordance with the NTS Formula;38 and

d) that BT be required to pay a penalty under section 36 of the Act.39

3.12

3.13

37

C&W indicated that its complaint was supported by:

•

Centrica;

•

ntl; and

•

Tiscali.40

Thus also contacted Ofcom in March 2005 and asked to be considered as a

stakeholder in this case.

C&W submission to Ofcom of 15 March 2005, paragraph 5.24.

I.e. the methodology of calculating charges using the NTS Calculator (see paragraphs 2.27 et seq

above).

39

C&W submission to Ofcom of 15 March 2005, paragraph 12.2.

40

C&W submission to Ofcom of 15 March 2005, paragraph 13.1. Centrica has since been acquired by

The Carphone Warehouse Group plc (“CPW”). ntl is now part of Virgin Media. The complaint, which

was made by Energis prior to C&W’s acquisition of Energis (see footnote 1), also listed C&W as

supporting the complaint.

38

24

The investigation

3.14

On 8 April 2005 Ofcom opened an investigation into the complaint under the Act and

Article 82 and published an entry on its Competition Bulletin setting out the details of

the investigation.41

Period of investigation

3.15

This investigation relates to the period of the alleged abuse i.e. the period of time that

NCCN 500 was in place, which was 1 May 2004 to 31 December 2005, i.e. 20

months.

Evidence gathered

3.16

In order to investigate C&W’s allegations, Ofcom gathered evidence from a number

of parties, as set out in the following paragraphs.

Evidence gathered from BT

3.17

3.18

Ofcom requested information from BT in connection with its investigation in several

ways:

•

formal Notices under section 26 of the Act;

•

follow-up questions to BT’s responses to Notices under section 26 of the Act; and

•

informal requests for information.

Before reaching its provisional decision, Ofcom sent BT 14 section 26 Notices, as set

out in Table 2 below:

41

www.ofcom.org.uk/bulletins/comp_bull_index/comp_bull_ocases/open_all/cw_823/. On 7 April 2004

Ofcom wrote to the Office of Fair Trading (“OFT”), informing the OFT that it intended to exercise

prescribed functions (as defined under Regulation 2(j) of the Competition Act 1998 (Concurrency)

Regulations 2004) in relation to the complaint and asked the OFT to confirm that it agreed that Ofcom

was the competent person to exercise prescribed functions in relation to the complaint. The OFT

replied on the same date confirming that Ofcom was the competent person best placed to consider

the complaint.

25

Table 2: Details of section 26 Notices sent to BT during the course of the investigation

Date of Notice

Date of BT’s response(s)

Purpose of Notice

22 April 2005

13 May 2005

Provision of documents related to BT’s

decision to impose the price increases

notified in NCCN 500.

19 May 2005

27 May 2005

6 June 2005

Details of volumes of NTS calls

terminated by BT and revenues

received by BT in respect of those calls.

11 July 2005

Description of BT’s NTS business.

12 July 2005

Details of BT’s top 10 NTS service

provider customers.

28 June 2005

14 July 2005

21 July 2005

12 July 2005

14 July 2005

Copies of BT’s management accounts

and business cases relevant to its NTS

call termination business.

Details of volumes of NTS calls

originated by BT.

21 July 2005

9 September 2005

13 September 2005

24 August 2005

26 August 2005

Clarification of relevant transfer charges

in BT’s management accounts.

25 August 2005

9 September 2005

Details of volumes of NTS calls

originated by BT.

11 October 2005

11 October 2005

17 October 2005

Financial Information derived from BT’s

regulatory costing systems (see Section

6) required for Ofcom’s investigation of

C&W’s allegations of excessive pricing

and margin squeeze.

Information on volumes of calls transited

by BT.

21 October 2005

4 November 2005

Financial information derived from BT’s

regulatory costing systems required for

Ofcom’s investigation of C&W’s

allegations of excessive pricing.

10 November

2005

18 November 2005

Financial information derived from BT’s

regulatory costing systems information

required for Ofcom’s investigation of

C&W’s allegations of excessive pricing.

14 November

2005

2 December 2005

Provision of documents related to BT’s

decision to impose the price changes

notified in NCCN 651.

14 December 2005

26

Date of Notice

Date of BT’s response(s)

Purpose of Notice

14 December

2005

19 December 2005

Financial information derived from BT’s

regulatory costing systems required for

Ofcom’s investigation of C&W’s

allegations of excessive pricing.

24 January 2006

3 February 2006

Financial information derived from BT’s

regulatory costing systems required for

Ofcom’s investigation of C&W’s

allegations of excessive pricing.

6 February 2006

6 March 2006

10 March 2006

24 March 2006

24 April 2006

28 April 2006

3 May 2006

Financial information derived from BT’s

regulatory costing systems required for

Ofcom’s investigation of C&W’s

allegations of excessive pricing.

Provision of documents related to BT’s

contracts for the provision of NTS

hosting.

5 May 2006

3.19

Ofcom requested further information from BT by way of follow-up questions to BT’s

responses to Notices under section 26 of the Competition Act 1998 on a number of

occasions, as set out in Table 3 below:

Table 3: Follow-up information requested from BT during the course of the

investigation

Date of Ofcom’s

request

Details of Ofcom’s request

Date of BT’s

response

23 May 2005

Letter from [] (Ofcom) to [] (BT)

requesting further information on BT’s

response of 13 May 2005 to Ofcom’s Notice of

22 April 2005.

27 May 2005

13 December

2005

Letter from [] (Ofcom) to [] (BT)

requesting further information on BT’s

response of 2 December 2005 to Ofcom’s

Notice of 14 November 2005.

14 December 2005

20 December

2005

Letter from [] (Ofcom) to [] (BT) with

follow-up questions on BT’s response of 13

October to Ofcom’s Notice of 11 October, BT’s

response of 17 October to Ofcom’s Notice of

11 October; BT’s response of 4 November to

Ofcom’s Notice of 21 October and BT’s

response of 18 November to Ofcom’s Notice of

10 November.

30 December 2005

3.20

13 January 2006

20 January 2006

Ofcom requested information from BT informally on a number of occasions, as set

out in Table 4 below:

27

Table 4: Other information requested during the course of the investigation

Date of Ofcom’s

request

Details of Ofcom’s request

Date of BT’s

response

27 January 2006

Letter from [] (Ofcom) to [] (BT) inviting BT’s

comments on Ofcom’s financial analysis of BT’s voice

NTS call termination/hosting business.

16 February 2006

12 May 2006

Letter from [] (Ofcom) to [] (BT) asking BT to

clarify how it accounts within its regulatory costing

systems for the effect of non-geographic number

portability.

23 May 2006

28 July 2006

8 September 2006

3.21

3.22

BT made a number of other submissions that Ofcom took into account in its

investigation, as follows:

•

BT’s response of 7 January 2005 to the market review consultation;

•

letter from [] (BT) to [] (Ofcom) of 1 April 2005 setting out BT’s comments on

the complaint; and

•

letter from [] (BT) to [] (Ofcom) of 20 April 2006 setting out BT’s comments

on the continuing investigation, including two Annexes providing details of other

OCPs’ retention on calls to NTS numbers, differences between the charges

notified in NCCN 500 and NTS Calculator rates, and BT’s analysis of retail prices

for calls to NTS numbers.

Ofcom and BT discussed various aspects of Ofcom’s investigation, either face to

face or by telephone, on the following dates:

•

4 July 2005;

•

18 August 2005;

•

2 September 2005;

•

29 September 2005;

•

11 October 2005;

•

19 October 2005;

•

2 December 2005;

•

7 April 2006; and

•

16 June 2006.

Evidence gathered from C&W

3.23

28

In addition to C&W’s submission of 15 March, Ofcom considered evidence provided

by C&W in various different ways on a number of occasions.

3.24

3.25

3.26

Ofcom sent C&W five section 26 Notices over the course of the investigation:

•

19 May 2005 (to Energis and C&W) requesting calls volumes for the purposes of

enabling Ofcom to calculate market shares;

•

28 June 2005 (to Energis and C&W) requesting details of their respective

businesses and the impact of NCCN 500; and

•

23 March 2006 (to C&W only) requesting clarification of the impact of nongeographic number portability (“NGNP”) on the investigation (see following

paragraph).

C&W made a number of other submissions that Ofcom took into account in its

investigation:

•

an email of 22 April 2005 setting out in writing a number of comments made by

C&W in a meeting with Ofcom 6 April 2005 relating to issues raised in the

complaint;

•

a letter of 18 August 2005 setting out in writing a number of comments made by

C&W in a meeting with Ofcom 11 August 2005 relating to issues raised in the

complaint;

•

a letter of 6 September 2005 setting out C&W’s comments on the appropriate

approach to Ofcom’s analysis of the alleged margin squeeze;

•

an email of 9 December 2005 attaching C&W’s comments on the impact of

NCCN 651 on the investigation;

•

a letter of 1 March 2006 about the potential impact on the investigation of issues

relating to NGNP;

•

a further letter of 10 March 2006 about the potential impact on the investigation of

issues relating to NGNP;

•

a letter of 21 April 2006 clarifying C&W’s position with regard to issues relating to

NGNP;

•

a letter of 12 May 2006 containing a review of previous submissions made by

C&W in light of its letters to Ofcom of 1 March 2006 and 10 March 2006; and

•

a letter of 23 June 2006 commenting on the relevance of issues relating to NGNP

to Ofcom’s decision.

Ofcom and C&W met to discuss various aspects of Ofcom’s investigation on the

following dates:

•

6 April 2005;

•

11 May 2005;

•

8 June 2005;

•

11 August 2005;

29

•

29 November 2005;

•

15 March 2006;

•

12 April 2006;

•

7 June 2006; and

•

16 June 2006.

Evidence gathered from third parties

3.27

Ofcom gathered evidence from third parties as follows:

•

section 26 Notices of 19 May 2005 to COLT Telecom Ltd, Centrica

Telecommunications, Easynet Group Plc, Gamma Telecom Holdings Ltd

(“Gamma”), Global Crossing (UK) Telecommunications Ltd, Kingston

Communications Ltd, MCI Worldcom Ltd, ntl Group Limited (“ntl”), Telewest

Communications Plc (“Telewest”), Thus Plc (“Thus”), Tiscali UK Limited (“Tiscali”)

and Your Communications Ltd and section 26 Notice of 29 June 2005 to Opal

Telecom Limited, requesting volume information for the purpose of enabling

Ofcom to calculate market shares;

•

section 26 Notices of 28 June 2005 to Centrica, C&W, Energis (see footnote 1);

Gamma; Hutchison 3G UK Ltd (“3”); ntl; O2 Plc (“O2”); Orange Limited

(“Orange”); T-Mobile Limited (“T-Mobile”); Telewest; Thus; Tiscali; Vodafone Ltd

(“Vodafone”).

•

section 26 Notice of 16 May 2006 to FlexTel Ltd and section 26 Notice of 18 May

2006 to IV Response Ltd.

The draft decision

3.28

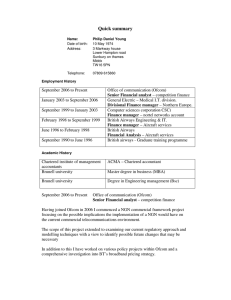

On 23 July 2007 Ofcom provided a draft decision to BT, C&W and four other parties