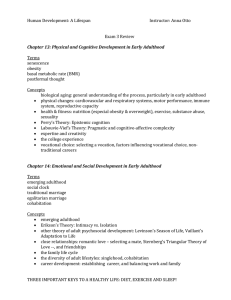

Health Implications of a Delayed Transition into Adulthood

advertisement