Chapter 13 Summary Once body structures reach maximum

advertisement

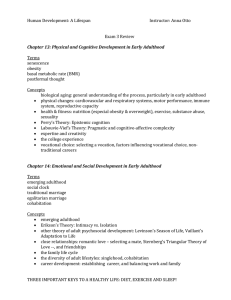

Chapter 13 Summary Once body structures reach maximum capacity and efficiency, biological aging begins. The combined result of many causes, it can be modified through behavioral and environmental interventions. In early adulthood, gradual changes occur in physical appearance and body functioning, including declines in athletic skills, in the endocrine and immune systems, and in reproductive capacity. Economically advantaged, well-educated individuals tend to sustain good health over most of their adult lives, whereas the health of lower-income individuals with limited education declines. SES differences in health-related living conditions and habits are largely responsible. Overweight and obesity, strongly associated with serious health problems, have increased dramatically in many Western nations. Today, Americans are the heaviest people in the world. Young adults are more likely than younger or older people to smoke cigarettes, use marijuana, take stimulants, or engage in binge drinking. Monogamous, emotionally committed relationships are more typical than casual sex among young adults, and attitudes toward same-sex couples have gradually become more accepting as a result of greater exposure and interpersonal contact. Many Americans will contract a sexually transmitted disease (STD) at some point in their lives; the deadliest STD, AIDS, is the sixth-leading cause of death among U.S. young adults. An estimated 18 percent of American women have endured rape; many more have experienced other forms of sexual aggression, sometimes with lasting psychological effects. Women’s menstrual cycle presents unique health concerns, including premenstrual syndrome, an array of symptoms preceding the monthly period. Psychological stress is related to a wide variety of unfavorable health outcomes. As SES decreases, exposure to diverse stressors rises—an association that likely plays an important role in the strong connection between low SES and poor health. The unique challenges of early adulthood make it a particularly stressful time of life. Social support can provide a buffer against psychological stress. The cognitive-developmental changes of childhood and adolescence extend into adulthood, as seen in the development of epistemic cognition (reflection on one’s own thinking process); a movement from dualistic, right-or-wrong thinking toward relativistic thinking; and a shift from hypothetical to pragmatic thought, with greater use of logic to solve realworld problems. These cognitive changes of early adulthood are supported by further development of the cerebral cortex, especially the prefrontal cortex and its connections with other brain regions. Expertise develops in adulthood as individuals master specific complex domains. College serves as a formative environment in which students can devote their attention to exploring alternative values, roles, and behaviors. Personality, family influences, teachers, and gender stereotypes all influence vocational choice as young adults explore possibilities and eventually settle on an occupation. Non-college-bound young people have a particular need for apprenticeships and other forms of preparation for productive, meaningful lives. Berk / Development Through the Lifespan, 6e 232 Copyright © 2014