Working Papers - GGZ Nederland

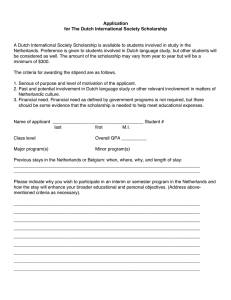

advertisement