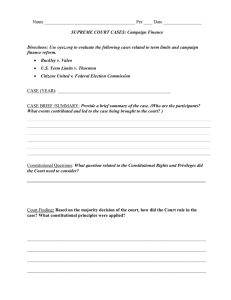

The Consitutionality of Restrictions on Individual Contributions to

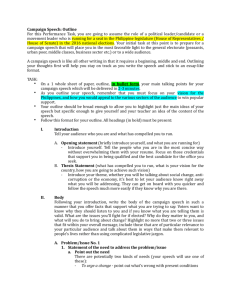

advertisement