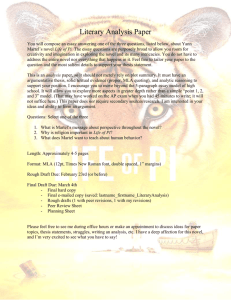

The Constructive Imagination: Life of Pi, Historio

advertisement