Meeting societal challenges

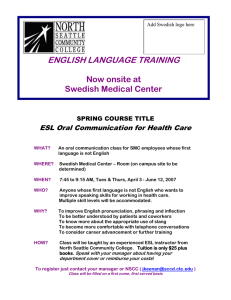

advertisement