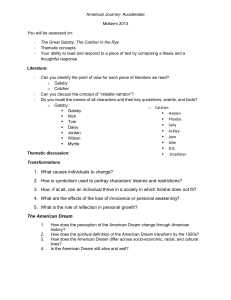

The American dream and literature: how the themes

advertisement