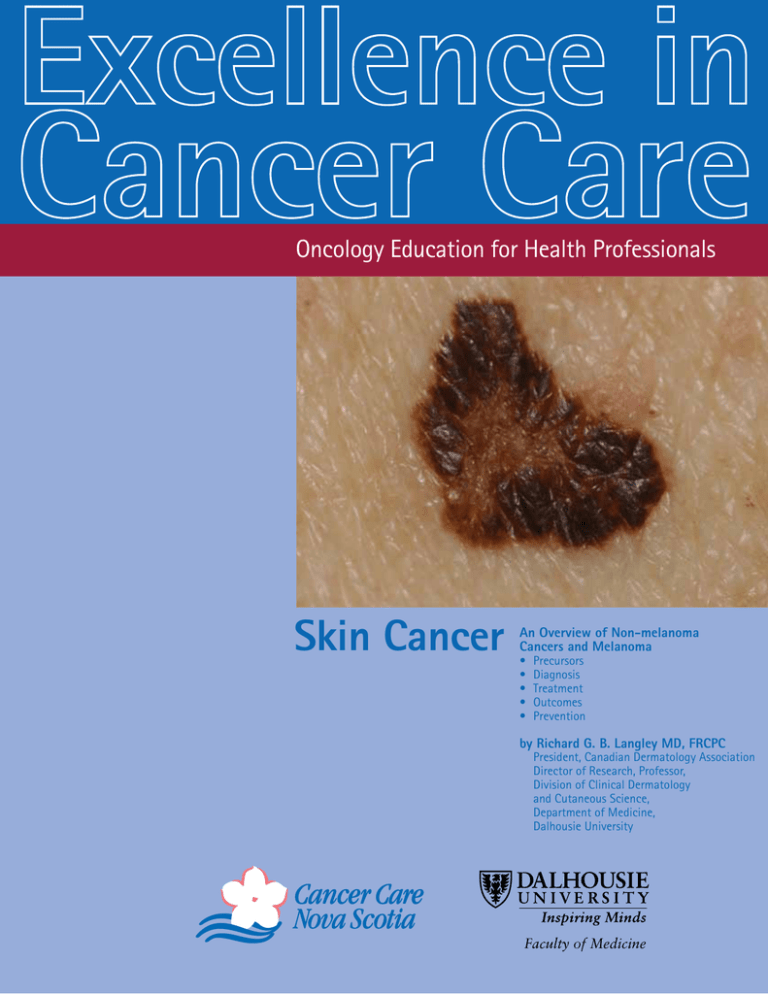

Skin Cancer - Cancer Care Nova Scotia

advertisement