Who Graduates with Excessive Student Loan

advertisement

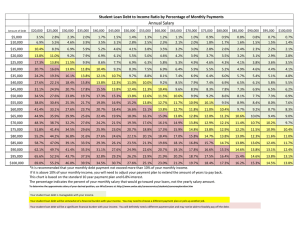

Student Aid Policy Analysis Papers Who Graduates with Excessive Student Loan Debt? www.studentaidpolicy.com/excessive‐debt/ Mark Kantrowitz President MK Consulting, Inc. December 14, 2015 Executive Summary Student loan debt has been growing rapidly over the last decade. But, while milestones may be impressive, what matters more is the growth in excessive student loan debt at graduation. A borrower has excessive student loan debt when the borrower graduates with more debt than he or she can afford to repay in a reasonable amount of time, such as within 10 years of graduation. This paper defines excessive debt as occurring when the borrower’s debt‐service‐to‐income ratio – the percentage A borrower has excessive of monthly gross income devoted to repaying student loan student loan debt when 10% or debt – is 10% or more under a standard 10‐year repayment more of a borrower’s gross plan. income must be devoted to This paper provides a rational justification for using the 10% repaying the borrower’s debt‐service‐to‐income ratio as a cap on affordable student student loan debt, assuming a loan debt. It derives the threshold by assuming that part of 10-year repayment term the after‐tax increase in income for Bachelor’s degree recipients (as compared with high school graduates) is available to repay student loan debt, assuming a 10‐year repayment term. The 10% threshold corresponds to using half of the additional net income to repay student loan debt. The paper also derives a 15% debt‐service‐to‐income threshold as a “stretch limit” by assuming that three‐quarters of the additional net income is available to repay student loan debt. The 10% and 15% debt‐service‐to‐income thresholds are also consistent with the rule of thumb that total student loan debt at graduation should be less than the borrower’s expected annual starting salary. This paper presents several other new results concerning students graduating with excessive student loan debt. The percentage of Bachelor’s degree recipients graduating with excessive student loan debt has been growing for the last three decades. But, the percentage of Bachelor’s degree recipients graduating with student loan debt who graduate with excessive debt has remained at slightly more than a quarter of Bachelor’s degree recipients who graduate with student loan debt for the last two decades. This suggests that the growth in the percentage of Bachelor’s degree recipients with excessive debt is driven by the overall growth in the percentage of students who must borrow to pay for college. Students who graduate with excessive student loan debt are more likely to delay major life‐cycle events, such as buying a home, getting married and having children, than students who graduate with affordable debt. Students who graduate with excessive debt are more likely to take a job outside their field, to work more than desired and to work more than one job. They are also significantly more likely to say that their education debt influenced their employment plans. Students who graduate with excessive debt are just as likely to own a car as students who graduate with affordable debt, but are less likely to have a car payment of $350 or more. Thus, graduating with excessive student loan debt can be the difference between owning a new car and a used car. Students who graduate with excessive debt are less likely to feel that their undergraduate education was worth the financial cost, as of one year after graduation. ‐1‐ Growtth in Stud dent Loaan Debt Rapid growth in the am mount of outsstanding stud dent loan deb bt has drawn the t attention of news med dia “ loan problem.” Outstanding sttudent loan debt exceeded d credit card debt and the public to the “student in 2010, auto a loans in 2011 2 and $1 trillion t in 201 12, now secon nd only to hom me mortgagee debt. While thee growth in ou utstanding stu udent loan deebt is notewo orthy, the imp pact on individual borroweers matters more. m This chaart, which is based b on dataa from the Naational Postseecondary Stud dent Aid Stud dy (NPSAS), demonstrates d s the steady growth g in thee percentage of Bachelor’ss degree recip pients who graduate with student loan debt an nd the average debt at graduation for th hose who graaduate with debt. d Growth in SStudent Loan De ebt at Grraduatio on for Baachelor'ss Degree e Recipie ents Average Stud dent Debt % Graduating with Student Loan ns 80% $60,000 0 $50,000 0 $40,000 0 49.4% % 70.2% 69.0% 66.5% 67.7% 65 5.4% 70% 2% 64.2% 62.2% 63.2 70.9% 60.3% % 69.6% 58.4% 1% 68.3% 67.1 60% % 65.9% 64.8% 63.7% 62.7% 61 1.2% 59.3% 50% 53 3.7% 40% $30,000 0 45.5% 30% $20,000 0 20% $10,000 0 10% 2014‐15 2013‐14 2012‐13 2011‐12 2010‐11 2009‐10 2008 09 2008‐09 2007‐08 2006‐07 2005‐06 2004‐05 2002‐03 2003‐04 2001 02 2001‐02 2000‐01 1999‐00 1998‐99 1997‐98 1996‐97 1994‐95 1995‐96 1993‐94 0% 1992‐93 $0 0 But, the growth g in deb bt at graduatio on is not neceessarily a problem, if mostt borrowers can c afford to repay r their loans. So, it is imp portant to ask: How manyy students aree graduating with w excessivee debt? ‐2‐ Defining Excessive Debt Student loan debt is excessive when the borrower cannot afford to repay it in full within a reasonable amount of time, such as within 10 years or less after graduation. The standard repayment term for federal student loans is 10 years. Borrowers can reduce their monthly loan payment by choosing a longer repayment term. For example, extended repayment and income‐ driven repayment plans can increase the repayment term to 20, 25 or even 30 years. But, increasing the repayment term also increases the total amount paid over the life of the loan. Borrowers who increase the repayment term will still be repaying their own student loans when their children enroll in college. They will be less likely to have saved for their children’s college education and they will be less willing to borrow to help them pay for college. Thus, the burden of repaying excessive student loan debt will be severe enough to affect the next generation’s ability to pay for college. Determining whether the student loan debt is affordable requires a comparison of debt with income, not debt by itself. Six‐figure student loan debt might be excessive for a borrower with just a Bachelor’s degree in a low‐paying liberal arts field, but not for a borrower who earns an advanced degree, such as an M.D. in a lucrative specialty like oncology, cardiology or orthopedics. To determine whether the student loan debt is affordable, the monthly loan payment must be compared with monthly income. Many students pursue a college education in order to obtain a better‐paying job. Accordingly, it is reasonable to require that the incremental increase in net income after taxes from obtaining a college degree should be sufficient to repay the student loan debt. Moreover, one could argue that half of the increase in take‐home pay should be available for repaying student loans and half for other priorities, so that the college graduate derives an immediate financial benefit from earning a college degree. Table 502.30 of the 2014 Digest of Education Statistics provides data on the median annual earnings of full‐time, year‐round workers age 25 to 34 by educational attainment for selected years from 1995 to 2013.1 This data is based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS). In 2013, the median annual earnings for full‐time, year‐round workers with only a Bachelor’s degree in the decade from age 25 to age 34 was $48,530, compared with $30,000 for workers with just a high‐school diploma or GED. This yields an average $18,530 increase in annual gross income from obtaining a Bachelor’s degree. Assuming a 25% federal income tax rate, 7.65% in FICA taxes and up to 9.8% in state and local income taxes, this yields $10,655 after taxes, or 22.0% of gross income. Half of this figure is 11.0%, setting a reasonable limit on the percentage of income available to repay student loan debt. Table P‐24 of historical income tables for the Current Population Survey (CPS)2 provides similar data concerning median earnings by educational attainment for full‐time, year‐round workers age 25 and older.3 However, unlike table 502.30, this data is not limited to the decade from age 25 to 34. Nevertheless, this income data yields a similar result, capping the percentage of income reasonably available to repay student loan debt at 11.2% of gross earnings in 2013 and 2014 and around 10.2% in the early 1990s. 1 http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d14/tables/dt14_502.30.asp https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/people/ 3 https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/people/2014/p24.xls 2 ‐3‐ This chart shows limits based on percentages of historical income data derived from Table 502.30. Percentage of Income Available to Repay Student Loans, 1995‐2013 12.0% 10.0% 10.7% 9.8% 9.4% 10.2% 10.0% 2007 2008 9.1% 10.4% 9.6% 9.6% 9.6% 2009 2010 2011 11.0% 8.0% 6.0% 4.0% 2.0% 0.0% 1995 2000 2003 2005 2012 2013 As this chart demonstrates, the debt‐service‐to‐income percentage has averaged about 10.0% for the last two decades. Using a similar approach to base the stretch limit on three‐quarters of the increase in net income after taxes would yield a percentage of gross income that averages around 15%. Thus, student loan debt at graduation should be considered affordable if the monthly loan payments assuming a 10‐year repayment term are less than 10% of gross monthly income. The student loan payments will still be affordable, but more of a financial stretch for the borrower, if the payments are less than 15% of gross monthly income. To set this in context, this table shows a histogram of debt‐service‐to‐income ratios for Bachelor’s degree recipients in 2007‐08 based on 2009 income, using the 2012 follow‐up to the 2007‐08 Baccalaureate & Beyond longitudinal study (BB12). The mode is at 7% and the median is at 8%. Distribution of Monthly Loan Payment as Percent of Monthly Income 10 8 6 4 2 1% 2% 3% 4% 5% 6% 7% 8% 9% 10% 11% 12% 13% 14% 15% 16% 17% 18% 19% 20% 21% 22% 23% 24% 25% 26% 27% 28% 29% 30% 31% 32% 33% 34% 35% 0 ‐4‐ This table shows the percentage of Bachelor’s degree recipients graduating in 2007‐08 with excessive student loan debt for various caps on the debt‐service‐to‐income ratio, based on BB12 data. Thus, the 10% threshold corresponds to about a quarter of Bachelor’s degree recipients graduating with excessive student loan debt. Cap on Percent of Debt‐Service‐to‐Income Bachelor’s Degree Recipients Ratio Graduating with Excessive Debt 5% 49.3% 8% 33.7% 10% 27.2% 15% 16.2% 20% 10.0% 25% 6.6% Note that data for the first year after graduation tends to represent a ceiling on the amount of student loan debt and a floor on the amount of income, since student loan debt tends to decrease and income tends to increase over the borrower’s career. So, the debt‐to‐income and debt‐service‐to‐income ratios will tend to decrease over time. This definition of excessive debt in terms of the debt‐service‐to‐income ratio represents a more direct measure of whether students are graduating with affordable student loan debt than the cohort default rate (CDR). The cohort default rate measures the percentage of students entering repayment during one federal fiscal year who default by the end of a subsequent federal fiscal year. Defaulting on a student loan is a potential consequence of excessive debt, but not the only possible consequence. Also, some borrowers default on their student loans for reasons other than affordability of the debt. So, the cohort default rate is, at best, an indirect measure of whether students are graduating with affordable student loan debt. The CDR does not measure other non‐paying statuses, such as deferments, forbearances and delinquencies. Moreover, borrowers who graduate with excessive debt might reduce the debt‐service‐ to‐income ratio by choosing alternate repayment plans that stretch out the repayment term instead of defaulting. Also, the cohort default rate is prone to manipulation by colleges that encourage borrowers to apply for deferments and forbearances, pushing the default outside the measurement window. The derivation of a 10% to 15% cap on the debt‐service‐to‐income ratio is also more rational than the flawed reasoning used to justify an 8% cap on the debt‐service‐to‐income ratio in the 2014 gainful employment regulations.4 The regulations selectively cited papers that based an 8% cap on the difference between mortgage underwriting standards for all debt and mortgage underwriting standards for mortgage debt. In addition to arbitrarily overlooking similar approaches that justified different caps on the debt‐service‐to‐income ratio, the regulations’ derivation of the student loan cap from mortgage underwriting standards assumes that mortgage lenders know more about affordable student loan debt than student loan experts. It also assumes that student loan debt is affordable only if the borrower is able to afford to buy a home instead of renting an apartment.5 4 Federal Register 79(211):64890 ‐65103, October 31, 2014. See specifically the discussion that begins on page 64917. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR‐2014‐10‐31/pdf/2014‐25594.pdf 5 The Administrative Procedure Act requires federal agencies to provide a reasoned basis for justifying regulations, but there is no requirement that the reasoned basis involve good reasoning. ‐5‐ Rule of o Thumb b: Total Debt D Lesss than Annual A In ncome The rule of o thumb thatt total studen nt loan debt at graduation should be lesss than the exxpected annu ual starting saalary corresponds to a perrcentage of grross monthly income within the range of 10% to 15% %, as shown byy this table. This T table assu umes a 10‐year repaymentt term. Accordingly, the rule of thumb is consistent with the disstinction betw ween affordab ble and excesssive student loan debt. In nterest Rate 0.0% 1.0% 2.0% 3.0% 3.4% 4.0% 4.29% Percentage e of Perccentage of Gross Incom me Interest Rate Grosss Income 10..0% 5.0% 12.7% 10..5% 6.0% 13.3% 11..0% 6.8% 13.8% 11..6% 7.0% 13.9% 11..8% 8.0% 14.6% 12..1% 8.5% 14.9% 12..3% 9.0% 15.2% Percen ntage of College C G Graduate es with Excessive E Debt Using the 10% debt‐se ervice‐to‐income ratio as a threshold on n affordable vs. v excessive debt, d it becom mes possible to calculate th he percentagee of college students who graduate witth excessive student s loan debt. d This chartt shows how the t percentagge of Bachelo or’s degree reecipients who o graduated with w excessivee student lo oan debt has changed over the last four decades. Exxcessive studeent loan debt is based on the t 10% cap on o the debt‐service to inco ome ratio, inccome the year after graduaation and a 10‐year repayment term. Datta for 1993‐94 4, 2000‐01 an nd 2007‐08 arre based on th he Baccalaureeate and Beyond (B&B) longitudin nal studies. Data for 1976‐‐77, 1985‐86 and a 1989‐90 are based on n a similar series of studiess, the Survey of Recent College Graduatess (RCG). This chart c shows an a increasing trend in the percent of Bachelor’s degree recipients who are graduatingg with excessiive student lo oan debt. Pe ercent of Bachellor's Deggree Reccipients who Grraduate with Exccessive Debt D 16 6.0% 14.4% 14 4.0% 1 11.9% 12 2.0% 9 9.8% 10 0.0% 8 8.0% 8.3% 6.7 7% 6.5% 1976 6‐77 1985‐86 6 6.0% 4 4.0% 2 2.0% 0 0.0% 89‐90 198 ‐6‐ 19 993‐94 20 000‐01 2 2007‐08 This chartt uses the sam me data to calculate the peercentage of Bachelor’s deegree recipien nts with excessive student lo oan debt as a percentage of o those graduating with student loan debt, d not all Bachelor’s B degree recipientss. When those e who graduaate with no deebt are omittted, slightly more m than a quarter of Bachelor’s degree recipients who borrowed for their t educatio on are graduaating with exccessive studeent loan debt. Pe ercent of Bachelorr's Degree e Recipients with Stud dent Loan ns who Grraduate with w Exce essive Deb bt 35.0% % 2 28.9% 30.0% % 25.0% % 27.5% 27.2% 2000‐01 2007‐08 22.9% % 20 0.0% 20.0% % 14.3 3% 15.0% % 10.0% % 5.0% % 0.0% % 1976‐77 1985‐‐86 198 89‐90 19 993‐94 This demo onstrates that a relatively constant percentage of sttudents who borrow b are grraduating witth excessive debt. It suggests that the recent growtth in the perccentage of Bachelor’s degrree recipientss who wth in the peercentage of students s who o must borrow w to are graduating with exxcessive debt is due to grow pay for co ollege, due to a shift in thee burden of paaying for colleege from the federal and state s governm ments to families. Overall, an average of 12.6% of monthly incomee is used to repay student loans l the year after graduation for 2007‐0 08 Bachelor’ss degree recip pients who grraduated with h student loan n debt, based d on BB12 datta. The averaage decreasess to 8.9% wheen students who w graduated with no deb bt are includeed. Women are a more likely to graduatee with excessiive debt than n men (29.1% to 24.3%). Th hey also havee a higher aveerage debt‐se ervice‐to‐inco ome ratio (13.2% to 11.6% %), mostly duee to women earning e lower 6 income th han men after graduation, even when employed e in the t same occupations. Caucasian n students are e more likely to graduate with w excessive debt (30.0% %) than Black or African‐ American students (14 4.6%) or Hispaanic or Latino o students (21 1.2%). This maay be due to a greater incrrease in incomee for minority students who obtain colleege degrees, even though the average income is low wer than for Caucasian C students. It could also be duee to differencces in the balaance between n student and d parent ed ducation debtt. 6 Catherinee Hill and Chrisstianne Corbett, Graduating to t a Pay Gap: The T Earnings of o Women and Men One Yearr after College Gra aduation, AAU UW, 2012. http://www.aauw.org/research//graduating‐to‐‐a‐pay‐gap/ ‐7‐ Students majoring in theology (64.7%), law and legal studies (43.1%), communications (36.2%), agriculture (34.1%), education (33.9%), humanities (33.5%) and design (33.1%) are more likely to graduate with excessive debt, presumably due to the lower income in these fields of study. Students majoring in engineering (16.3%) and computer science (23.8%) are less likely to graduate with excessive debt, presumably due to the higher income in these fields of study. Students who borrowed private student loans are more likely to graduate with excessive student loan debt (36.4% vs. 22.8%). This may be because it is more difficult for dependent students to borrow excessively with federal student loans alone, given the low annual and cumulative loan limits on federal student loans. A college’s annual cost of attendance correlates with the percentage of students graduating with excessive student loan debt, as shown in this table based on BB12 data. College costs are a key driver of debt at graduation, so higher‐cost colleges are more likely to have more students graduating with excessive student loan debt. 2007‐08 Annual Percent Graduating Cost of Attendance with Excessive Debt Less than $10,000 22.2% $10,000 to $19,999 24.7% $20,000 to $29,999 29.5% $30,000 to $39,999 34.6% $40,000 or more 34.6% The college affordability index7 correlates with excessive student loan debt. Students for whom the college affordability index is 75% or more are more likely to graduate with excessive debt than students for whom the college affordability index is less than 25% (32.7% vs. 24.8%). Dependent students (as defined for federal student aid purposes) are more likely to graduate with excessive debt than independent students (30.2% vs. 23.2%). This is largely because students who are age 30 or older are much less likely to graduate with excessive student loan debt (16.4%), slightly more than half the rate for younger students. College graduates who work for the military (22.3%) or government (22.9%) are less likely to have excessive student loan debt than graduates who work for a for‐profit company (27.6%), a non‐profit organization (31.2%) or who are self‐employed (36.6%). Students who work in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) occupations are much less likely to graduate with excessive debt (14.8%) than students who work in non‐STEM occupations (28.2%). 7 The college affordability index is the ratio of the net price to total family income. Colleges that are more affordable for a student have a lower college affordability index. The net price is the difference between the annual cost of attendance and gift aid (grants, scholarships and other money that does not need to be earned or repaid). ‐8‐ This chartt shows that high‐income h B Bachelor’s deegree recipien nts are less likkely to have excessive e stud dent loan debt than low‐inccome Bachelo or’s degree reecipients, baseed on BB12 data. d Percent with Excessivve Debt P by An nnualized Salary S Perccentile, 20 009 45 5.0% 39 9.2% 40 0.0% 36.7% 35 5.0% 27.9% 30 0.0% 25 5.0% 19.3% % 20 0.0% 15 5.0% 9 9.7% 10 0.0% 5 5.0% 0 0.0% First Quintile Seccond Quintile t 20%) (2 20% to 39%) (Less than Third Quintille (40% to 59% %) Fourth Qu uintile (60% to 79%) 7 Fifth Quintile (80% or more) This chartt shows that Bachelor’s B deegree recipien nts with higheer student loaan balances are more likelyy to have exceessive studentt loan debt th han Bachelor’’s degree reciipients with lo ower studentt loan balancees, based on BB12 data. Percent wiith Excessive Debt P by Cumullative Loan n Amount through 20 007‐08 70.0% 57.9% 60.0% 61.1% % 4.9% 54 50.0% % 35.9% 40.0% 38.5% 36.8% 27..9% 30.0% 20.6% 20.0% 10.0% 10.0% 0.0% Less than $10,000 to $20,0 000 to $30,000 0 to $40,000 to o $50,000 to $6 60,000 to $70,0 000 to $80,000 0 or 99 $49,999 $59,999 $69,999 $ $79 9,999 moree $10,000 $19,999 $29,999 $39,99 hooled studen nts are more likely to grad duate with exccessive debt (48.3%) than students with a Home‐sch high school diploma (2 27.1%) or GED D (25.9%). Students who w receive private scholaarships are more m likely to graduate with excessive debt d (31.2% vss. 26.8%), peerhaps becau use scholarship recipients are a more likeely to enroll att higher‐cost colleges. ‐9‐ High school GPA, undergraduate GPA, SAT test scores, disability status, participation in study abroad, status as a transfer student, institutional selectivity, in‐state vs. out‐of‐state enrollment and Federal Pell Grant recipient status do not seem to have a significant impact on whether the student graduates with excessive debt or not. Consequences of Graduating with Excessive Debt Students who graduate with excessive student loan debt are more likely to have borrowed private student loans (42.8% vs. 27.3%), based on BB12 data. Dependent undergraduate students cannot graduate with excessive debt using only federal student loans. Students who graduate with excessive student loan debt are more likely to feel that their undergraduate education was not worth the financial cost as of the year after graduation (35.8% vs. 22.2%) and more likely to say that the debt influenced their employment plans (64.3% vs. 41.6%), based on BB12 data. Students who graduate with excessive debt are less likely to have a car payment of $350 or more as of four years after graduation (44.9% vs. 54.1%) and to be paying a mortgage (34.1% vs. 42.5%), based on BB12 data. But, borrowers appear to be equally likely to have a car payment. Rather, excessive debt seems to manifest itself in a lower car payment and a lower monthly rent or mortgage payment, so that the student loan payment is a greater percentage of overall household debt payments. Curiously, students who graduate from for‐profit colleges tend to have higher car payments and higher monthly rent or mortgage payments, despite their higher student loan debt. These are some of the other reported consequences of graduating with excessive debt, based on BB12 data: Delayed buying a home (49.8% vs. 38.1%) Delayed getting married (27.1% vs. 20.9%) Delayed having children (36.4% vs. 27.9%) Took a job instead of enrolling in further postsecondary education (43.3% vs. 33.0%) Took a job outside of field (50.8% vs. 36.4%) Work more than desired (47.8% vs. 36.4%) Worked more than one job (33.0% vs. 23.4%) Potential Compliance with Gainful Employment The average debt‐service‐to‐income ratio is 15.2% for private non‐profit colleges, 12.6% for private for‐ profit colleges and 11.0% for public colleges, based on BB12 data. Using the 8% debt‐service‐to‐income ratio threshold used in the gainful employment regulations, 40.0% of Bachelor’s degree recipients at private non‐profit colleges would have excessive debt, compared with 33.8% of Bachelor’s degree recipients at private for‐profit colleges and 30.0% of Bachelor’s degree recipients at public colleges, based on BB12 data. This suggests that private non‐profit colleges would have more problems complying with the gainful employment regulations than private for‐profit colleges, if the gainful employment regulations were applied to Bachelor’s degree recipients at private non‐profit colleges. Most Bachelor’s degree granting institutions would have problems complying with the gainful employment regulations even if the threshold for affordable debt were set at 15%. ‐ 10 ‐ Correllation of Excessivve Debt with w Debtt and Inccome Previous studies s by oth her researcheers have repo orted that borrrowers with lower debt leevels are morre likely to default d than borrowers b witth higher debt levels. The data d concerning excessivee debt at graduatio on presented in this reportt is not consistent with theese previous studies. s This suggests s that financial stress s – the faailure to keep p debt in syncc with incomee – does not explain e the reesults reporteed by the previo ous studies. A previous study by the author of th his paper dem monstrates th hat default rattes increase with w increasees in uggesting thaat graduating with excessivve debt can be b a cause of the debt‐sservice‐to‐inccome ratio, su student lo oan default.8 This chart sho ows that the debt‐service‐‐to‐income raatio correlates with the percentagge of borrowe ers in a deferment or forbeearance, an in ndicator of financial stresss.9 Perccent in Defferment/Fo orbearance by Deb bt‐Service‐‐to‐Income e Ratio, 20 009 2 20.0% 17.6% 18.0% 16.0% 14.0% 14.2% 15.0% 15.7% % 12.6% 1 12.0% 10.0% 8.0% 6.0% 4.0% 2.0% 0.0% 5% or more 8 or more 8% 10% or moree 8 15% or more m 20% or more Mark Kan ntrowitz, Relatiionship of Defa ault Rates to Debt D and Incom me, August 17, 2010. www.finaid d.org/educators/20100817affordabilitymeasures.pdf 9 Defermen nts and forbeaarances are tem mporary suspensions of the obligation o to make m paymentss on a student loan. Interest may continue to o accrue duringg a deferment or o forbearancee. ‐ 11 ‐ This chartt shows that the t debt‐servvice‐to‐income ratio correlates with deffault rates. Percent in n Default in n 2012 by 200 09 Debt‐Se ervice‐to‐Income Ratio 3 3.5% 3 3.1% 3 3.0% 2.8% 2.6% 2 2.5% 3 3.2% 2..5% 2.2 2% 2 2.0% 1.5% 1.0% 0 0.5% 0 0.0% 5% or more 8% orr more 10% or o more 15% o or more 20% or o more 25% or more This chartt shows that higher h cumulaative undergrraduate debt through 2007‐08 correlattes with increased percent in n default in 20 012, based on n BB12 data. Percent in n Default in 2012 by Cumulativve Undergrraduate De ebt througgh 2007‐08 8 4 4.7% 5 5.0% 4 4.5% 4 4.0% 3.6% 3 3.5% $30,,000 to $39 9,999 $40,,000 to $49,999 3 3.5% 3 3.0% 2 2.5% 2 2.0% 1.5% 1.9% 2..0% $10,0 000 to $19 9,999 $20,0 000 to $29 9,999 1.1 1% 1.0% 0 0.5% 0 0.0% Less than $10,,000 ‐ 12 ‐ $50 0,000 to $7 74,999 This chartt shows that the t percentagge of Bachelo or’s degree recipients with excessive deebt increases with increasingg debt, based on BB12 datta. Percent with Excessivve Debt P by Cumulative Und dergraduatte Debt, 20 007‐08 70 0.0% 62.5% 66.0% 60 0.0% 50 0.0% % 43.9% 36.8% 40 0.0% 35..6% 26.2% 30 0.0% 20.5% 20 0.0% 11.4% % 10 0.0% 0 0.0% Less th han $10,000 to o $20,000 to $3 30,000 to $40,0 000 to $50,000 to $75,000 to $100,000 $10,00 00 $19,999 $29,999 $39,999 $ $49,,999 $74,999 $99,999 or more This chartt shows that the t percentagge of Bachelo or’s degree recipients with excessive deebt decreasess with increasingg income, bassed on BB12 data. d Pe ercent witth Excessive Debt by Annualizzed Salaryy in 2009 9 45 5.0% 40 0.0% 38.0% 35 5.0% 30 0.0% 25.2% % 25 5.0% 20 0.0% 15 5.0% 10.4% 10 0.0% 5 5.0% 1.3% 0 0.0% t $25,000 Less than $25,000 to $49,999 $ $50,000 to $74,999 9 $75,000 to o $99,999 ‐ 13 ‐ This chartt shows that Bachelor’s B deegree recipien nts with higheer annualized salaries havee lower debt‐‐ service‐to o‐income ratio os, based on BB12 data. Average e Debt‐Se ervice‐to‐‐Income Ratio R by Annualizzed Salaryy in 2009 9 30 0.0% 23.5% 25 5.0% 20 0.0% 15 5.0% 9.8% 10 0.0% 6.3% 4.1% 5 5.0% 0 0.0% Less than t $25,000 $ $50,000 to $74,999 9 $75,000 to o $99,999 $25,000 to $49,999 This chartt shows that Bachelor’s B deegree recipien nts with higheer cumulativee undergraduaate debt havee higher debt‐service‐to‐income ratio os, based on BB12 B data. Average e Debt‐Se ervice‐to‐‐Income Ratio R byy Cumulattive Unde ergraduate Debt, 2007‐08 40 0.0% 35.2% 35 5.0% 30 0.0% 27.3% 25 5.0% 18..2% 20 0.0% 15 5.0% 10 0.0% 10.3% 12.7% % 20.0% 14.3% 7.6% % 5 5.0% 0 0.0% Less th han $10,000 to o $20,000 to $3 30,000 to $40,0 000 to $50,000 to $75,000 to $100,000 $10,00 00 $19,999 $29,999 $39,999 $ $49,,999 $74,999 $99,999 or more ‐ 14 ‐ This chart shows that the distribution of debt is similar across income strata, so it is unlikely for borrowers with low debt to also have much lower income, thereby, yielding higher debt‐service‐to‐ income ratios. So, even if there is a minimum income threshold required for basic living expenses, it is unlikely to cause differences in ability to repay student loan debt for borrowers with low cumulative undergraduate debt. Distribution of Cumulative Undergraduate Debt by Annualized Salary in 2009 35.0% Less than $25,000 30.0% $25,000 to $49,999 25.0% $50,000 to $74,999 20.0% 15.0% $75,000 to $99,999 10.0% $100,000 or more 5.0% 0.0% Less than $10,000 to $20,000 to $30,000 to $40,000 to $50,000 to $10,000 $19,999 $29,999 $39,999 $49,999 $59,999 Cumulative Undergraduate Debt This chart is similar, but shows the distribution of annualized salary in 2009 by cumulative undergraduate debt. It shows that low‐income graduates aren’t any more or less likely to have lower cumulative undergraduate debt. Distribution of Annualized Salary in 2009 by Cumulative Undergraduate Debt 60.0% Less than $10,000 50.0% $10,000 to $19,999 40.0% $20,000 to $29,999 30.0% $30,000 to $39,999 $40,000 to $49,999 20.0% $50,000 to $59,999 10.0% 0.0% Less than $25,000 $25,000 to $49,999 $50,000 to $74,999 $75,000 to $99,999 $100,000 or more Annualized Salary in 2009 Perhaps, the results found in other studies depend more on college completion than the amount of student loan debt. After all, students who drop out of college tend to have less student loan debt than ‐ 15 ‐ students who graduate because they are enrolled for fewer payment periods. Thus, the amount of debt may be a dependent variable and not an independent variable, influenced by college completion as a confounding factor. Recommendations It is increasingly important to understand the consequences of excessive student loan debt because of the increasing prevalence of student loan debt. This paper discusses excessive student loan debt by Bachelor’s degree recipients only, due to the limitations of available data. It does not report on excessive debt by recipients of other degrees, such as Associate’s degrees, Certificates and more advanced degrees. It also does not report on excessive debt owed by students who drop out of college. It does not report on other reasons why students might fail to repay their student loans, such as dissatisfaction with the quality of their education. Recommendation: The U.S. Department of Education should initiate a study of the consequences of excessive student loan debt. This study can be implemented by tracking outcomes for all degree levels and for non‐completers in a manner similar to that of the Baccalaureate & Beyond (B&B) longitudinal study, namely as a follow‐up to a subset of participants in the quadrennial National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS). Congress should provide sufficient funding for this study to ensure that it occurs. Without funding, there is no guarantee that this study will be implemented, even if mandated by Congress. Although the 2009 follow‐up to the 2003‐04 Beginning Postsecondary Students longitudinal study (BPS:04/09) may be used to calculate the percentage of college graduates with Associate’s degrees and Certificates who have excessive debt, the data is not comparable with the data used in this paper from the Baccalaureate & Beyond (B&B) study for Bachelor’s degree recipients. The B&B study provides income data one year after degree attainment. The BPS study provides income data income data in 2009 for cumulative degree attainment during the prior six years. Even if one restricts the degree attainment to students who received a degree in 2007‐08, the BPS study still involves an additional restriction to students who first enrolled in 2003‐04. The BPS study also does not address whether graduate and professional school students are graduating with excessive student loan debt. Thus, the data in this table is at best suggestive. BPS:04/09 Percent of Cumulative Persistence and Degree Percent with Borrowers with Attainment as of 2008‐09 Excessive Debt Excessive Debt Attained Bachelor’s Degree 15.6% 24.4% Attained Associate’s Degree 5.2% 8.9% Attained Certificate 2.8% 4.7% No Degree, Still Enrolled 2.4% 5.3% No Degree, Left without Return 4.5% 9.5% Colleges often refer to student loans as a form of financial aid, arguing that student loans make college more affordable. Student loans delay the repayment obligation, but do not reduce or eliminate it. But, despite widespread claims that student loans make college more affordable, few, if any, colleges track whether their students are graduating with affordable debt. Monitoring long‐term trends is necessary for anticipating and identifying problems when they occur. If too many students are graduating with ‐ 16 ‐ excessive debt, it can affect the college’s reputation. It can also have an impact on charitable contributions to the college. Increasing awareness is the first step in exercising restraint. Recommendation: Each college and university should annually track the percentage of students graduating with excessive debt. The data should be disaggregated by degree level. Recommendation: Alternately, the U.S. Department of Education could track the percentage of students graduating with excessive debt for each college and university. This will require tracking of private student loans in addition to federal student loans. It will also require an approach that protects the privacy of individual student data, especially data concerning income. Perhaps, it could be implemented in a manner similar to the one used for the gainful employment regulations. Recommendation: Colleges and universities should include a discussion of excessive debt and the consequences of borrowing too much in their loan counseling programs. Students who are predicted to graduate with excessive debt based on borrowing patterns and academic major should be targeted for more aggressive loan counseling and financial literacy training. Recommendation: Financial aid award letters should be standardized to clarify distinctions between loans and grants. Increasing awareness of debt is the first step toward exercising restraint. The financial aid award letters should include an “excessive debt alert” for students who are predicted to graduate with excessive debt based on past borrowing patterns. ‐ 17 ‐