Research Strategies 19 (2003) 193 – 203

The emergence of learning objects: The reference

librarian’s role

John D. Shank

Penn State Berks-Lehigh Valley College, Reading, PA 19610, USA

Available online 17 February 2005

Abstract

Learning objects are beginning to draw much interest in higher education. They can be powerful

teaching and learning tools that the instructor can use both in and outside the classroom. This article

focuses on how reference and instruction librarians can play a critical role in locating appropriate

learning objects to enhance their library instruction courses in addition to assisting faculty in locating

learning objects for augmenting their courses.

D 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Learning objects have increasingly generated a great deal of interest and enthusiasm in the

online learning community and more recently have engendered similar interest and

enthusiasm in various other instructional technology groups. To confirm this, merely travel

to a conference that has a track focused on online or Web-based learning, or peruse a recent

technology and learning trade magazine. Learning objects have generated excitement

because they can be powerful assets in augmenting, enhancing, and streamlining the teaching

and learning process, not only in distance education, but in the traditional classroom as well.

The OCLC E-Learning Task Force (2003) emphasized that learning objects are bat

the heart of the learning/technology nexus.Q This task force also declared that it is

critical to assess what role libraries can play in the process of defining learning objects

and their repositories. Unfortunately, learning objects have not generated as much

E-mail address: jds30@psu.edu.

0734-3310/$ - see front matter D 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.resstr.2005.01.002

194

J.D. Shank / Research Strategies 19 (2003) 193–203

excitement in the library community, perhaps because librarians have not been exposed

to the emerging discussions and debates among instructional designers and technologists about learning objects.

This article aims to raise awareness of the role that reference and instruction librarians can

play in utilizing and locating appropriate learning objects both to enhance their own library

instruction classes and to assist college and university faculty in augmenting their courses. In so

doing, librarians will be playing a vital role in the use and adoption of learning objects by

faculty.

1. Defining learning objects

Confusion is expected any time existing vocabulary is applied to a new technological

concept. The OCLC E-Learning Task Force (2003) notes that the term blearning objectQ is

currently bnot yet definable in any specific sense, so it is accepted that a degree of semantic

confusion is inevitable.Q It is not surprising that the instructional systems design and

technology literature (Wiley, 2000; Friesen, 2003; Polsani, 2003) emphasizes the fact that the

definition of a learning object is debatable and contentious.

One widely cited general definition, from the Learning Object Metadata Working Group of

the IEEE Learning Technology Standards Committee (2001), is bany entity, digital or nondigital, which can be used, re-used or referenced during technology supported learningQ

(2002, Section 1.1, 1). This definition is extremely vague and much of the literature (Friesen,

2003; Polsani, 2003; Shepherd, 2000) asserts that it is too broad a definition to be meaningful.

David Merrill (2002) explains that, bas usually defined learning objects are of little use to

anyone.Q Consequently, many of the stakeholders have taken different directions in their

attempt to define a learning object, which has led to the creation of various definitions that are

tied to the primary interests and concerns of their proponents (Rehak & Mason, 2003). David

Wiley (2000) states that, bthe proliferation of definitions for the term dlearning objectT makes

communication confusing and difficult.Q

This semantic confusion coupled with the debate and disagreement over an agreed

upon, concise, and authoritative definition of a learning object makes it challenging to

formulate a working definition that librarians can use. Recognizing that it may be

quite some time until a single authoritative definition emerges, it is necessary to

choose a working definition of a learning object so that existing learning objects can

be located and utilized. Weller, Pegler, and Mason (2003), in their paper Putting the

Pieces Together: What Working with Learning Objects Means for the Educator,

attempt to break free of the debate by adopting a definition that is broad enough to

encompass most interpretations without rendering such a definition meaningless. The

definition of a learning object they propose in their paper is the definition that this

article adopts. The working definition of a learning object this paper will use is ba

digital piece of learning material that addresses a clearly identifiable topic or learning

outcome and has the potential to be reused in different contextsQ (Weller et al.,

2003).

J.D. Shank / Research Strategies 19 (2003) 193–203

195

2. Synopsis of a learning object and its benefits

In the current environment of semantic confusion, it is useful to examine a library learning

object to clarify the term and concept. It is also possible to gain a deeper understanding of

some of the benefits of using learning objects through an examination of how a reference and

instruction librarian could make use of a learning object. The Boolean Tutorial design by

Beau Morley and Katie Reifman (Morley & Reifman, 2003) (http://library.nyu.edu/research/

tutorials/boolean/boolean.html) from NYU’s Bobst Library is a good example of a library

learning object. This tutorial instructs students how to correctly use Boolean operators when

executing a search. What makes this tutorial a good example of a learning object is that it

accurately fits the aforementioned definition.

1. It is a reusable digital resource.

2. It includes a specific learning outcome (how to properly use Boolean operators) and

associated learning activities.

3. It is sharable across various instructional contexts both within and between educational

institutions.

The instructional systems design and technology literature (Metros & Bennett, 2002; Polsani,

2003; Rehak & Mason, 2003) mentions that one of the primary reasons why learning objects

have generated excitement within the online learning community is the reusability of learning

objects, or the ability to be able to share them and use them in various instructional contexts.

Ideally, a learning object can be simultaneously shared, reused and placed into multiple courses,

disciplines, and course management systems exactly when and where the instructor desires.

David Wiley explains that bdigital resources available on a computer network are dnonrival

resources’ because they can be utilized simultaneously by many peopleQ (Wiley, 2002).

A reference librarian could capitalize both on the ability to reuse and share the preexisting

Bobst Boolean Tutorial when teaching instructional sessions by having the professor assign

the learning object (which takes approximately 5–10 minutes to complete) before the class

meets. The students in the class would then have some prior exposure to the topic the

librarian would be covering, thus allowing the students to come more prepared for their

library instruction session. This also has the advantage of freeing up some of the introduction

time that the librarian would normally take in the classroom session.

Pre-exposure to ideas outside the classroom could be a great advantage to librarians who

are only given one or two class sessions to teach library instruction to an individual class. A

librarian would need to have the professor agree to assign the learning object before the

instruction session. However, the Bobst Boolean Tutorial only takes a few minutes to

complete; therefore, it is unlikely the professor would object because of an increased demand

on student time outside of the classroom.

Additionally, if the classroom that has Internet access, a projector, and screen, the librarian

can use the learning object in the classroom to further demonstrate the concepts behind

Boolean searching. Moreover, the learning objects would still be available after the class

session for students to practice with as often as they desire at their own pace, providing

196

J.D. Shank / Research Strategies 19 (2003) 193–203

reinforcement for the learning that took place during the class session. Reference librarians

both within and outside the university can utilize the Bobst Boolean Tutorial regardless of the

different instruction sessions they teach because the tutorial is in a digital format accessible

from the Web. Librarians are thus enabled to deliver, simultaneously or independently, a

consistent learning object about Boolean searching to a large group of students. Utilized in

this manner learning objects can be powerful tools to augment face-to-face classroom library

instruction as long as it is available and the instructional content is relevant and accurate.

The OCLC E-Learning Task Force (2003) notes that the instructional context of a learning

object is integral to any meaningful interpretation. James L’Allier (1997) further defines the

instructional components of a learning object as containing ban objective, a learning activity

and an assessmentQ and thereby includes them as integral attributes of a learning object. Thus,

one of the basic components of a learning object, the instructional context and components

(i.e., the educational framework—which includes learning outcomes, activities, and assessments) is important. Currently, there is no agreed upon pedagogy for constructing the

educational framework of a learning object, and there is very little existing literature about

using learning objects to enhance the traditional classroom and student learning. It is beyond

the scope of this paper to delve too deeply into a discussion about what pedagogical

paradigms should be used in creating learning objects. Nonetheless, it is useful to look at the

Bobst Boolean Tutorial to view how learning outcomes, activities, and assessments may be

integrated into a learning object to gain deeper appreciation of the benefits of a learning

object.

The Bobst Boolean Tutorial contains instructional components which include an objective

(student will be able to execute a Boolean search) and various learning activities. These

learning activities constitute a series of questions related to Boolean searching, with the

Fig. 1. Question from the Bobst Boolean Tutorial.

J.D. Shank / Research Strategies 19 (2003) 193–203

197

purpose of allowing the student to practice the concepts associated with using Boolean

operators. The tutorial then provides immediate feedback to each of the answers the student

chooses demonstrating an understanding, or lack thereof, of how to apply the searching

concepts (see Fig. 1).

Most learning objects also incorporate a combination of some or all of the following:

audio, video, animations, graphics, text, and some type of user interaction (which might

include text entry, drag and drop, multiple select, and/or button pushing). The Bobst Boolean

Tutorial is no different; it contains activities such as multiple select questions and answers and

animations which depict the concepts of the Boolean operators. Given that most learning

objects include some type of kinesthetic interaction and contain activities that require students

to interact with and receive feedback from the learning object in order to progress, students

are permitted to practice using the concepts. Notasha Boskic (2003) points out that Leegan,

Moore, and Hillman regard interaction as b. . .the key to effective learning.Q

To conclude this synopsis, it may also be useful to relate learning objects to traditional

educational materials. For example, an introductory textbook about library science is made up

of many component chapters, one of which might be a chapter on database searching. This

chapter would also consist of component subtopics, one of which might be Boolean

searching. A learning object similar to the Bobst Boolean Tutorial would be created if the

content from the topic about Boolean searching were removed from the textbook and

converted to a digital electronic format. To be complete, this learning object must include

both an instructional component that allows the student to practice and demonstrate specific

learning outcomes, as well as some variety of feedback or assessment.

3. Locating learning objects

The OCLC E-Learning Task Force (2003) remarks that learning objects are currently

difficult to locate and asserts that bin order for learning objects to have any kind of value, they

first require the use of semantically consistent, easily created metadata that allows for the

objects themselves to be easily found and transported between institutions and repositories.Q

Catalogers and systems librarians can play an important role in working to create systems

where learning objects can be cataloged, housed, and effectively retrieved; however, such

roles are beyond the scope of this article. Rather, this article focuses on what role reference

and instruction librarians can play in helping faculty locate learning objects in the current

environment.

Reference and instruction librarians can and should play a role in identifying learning

objects through repositories, breferitoriesQ (the term referitory, coined by Carl Berger, is used

to mean a digital library that only links or points to the learning object), and other online

libraries or databases in order to augment their own instruction and to assist instructors in

locating appropriate learning objects. These librarians should also seek to partner with

instructional developers, designers, and technologists at their local institutions when seeking

to appropriately integrate an existing learning object or to develop their own for an instruction

program or session.

198

J.D. Shank / Research Strategies 19 (2003) 193–203

Because of the aforementioned issues regarding the lack of agreement on the authoritative

definition of a learning object, it is not surprising that locating them is, to some extent, a

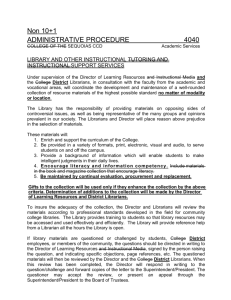

complex and difficult task as well. There are two important criteria that must be considered

when locating appropriate and relevant learning objects. First, what—identify the subject and/

or discipline the learning object could be classified under and second; where—determine the

best starting point to target the search (see Fig. 2).

When attempting to identify the subject or discipline the learning object could be classified

under, it is useful to use the existing schema of the various repositories and referitories. To

find a learning object on information literacy using a repository or referitory, one possible

classification to look under could be blibrary and information studies.Q It is then possible to

further narrow the search to a specific subset of the type of learning object by browsing under

the subject or classification scheme (most repositories and referitories have this option). Most

repositories and referitories do not use Library of Congress Subject Headings, however, and

consequently there is little consistency from one to the other. It is often necessary to identify

some key words or phrases that describe the learning object sought given that it is not always

possible to be able to make use of the subject or discipline classification of a particular

learning object.

It is also crucial to identify the type of learning object as this can help determine the

level of interactivity and instructional components. This refers to the medium of the

resource, such as complex animations, simulations, Web-based tutorials, or multimedia

presentations. In conjunction with the type of learning object desired, it is important to

identify the format, that is, the digital manifestation of or the technology utilized by the

resource, such as Flash, Authorware, Java, or QuickTime. The format can tell what

software will be needed in order to view and use the learning object. To expose students

to a particular aspect of information literacy such as evaluating Internet sources, a

librarian may want to locate a learning object that is a type of tutorial, with a specific

technical format such as a Flash file format, that lets the students progress through the

content as they successfully demonstrate the important components in evaluating Internet

Fig. 2. Learning object search criteria tree.

J.D. Shank / Research Strategies 19 (2003) 193–203

199

resources. The modules of Texas Information Literacy Tutorial (TILT), available at http://

tilt.lib.utsystem.edu, are a good example of this.

Finally, it is essential to determine the appropriateness of the learning object for the

audience. Most repositories and referitories will allow librarians to narrow and focus their

search for a specified level or audience, while other resources (e.g., search engines) will not.

There are a multitude of places to search to find learning objects. Accordingly, it is

not always a simple task to determine the best starting point to target the search (see Fig.

2). However, the best place to start is often with a repository or referitory, as they are

more focused on collecting, housing, or referring to learning objects. As mentioned

previously, Web-based repositories house the learning objects, while Web-based

referitories simply link or point to the resources. The advantage repositories have is

that the resource is under their control and can be archived while the referitories can

have broken and obsolete links.

Most repositories and referitories have a browse and search function. These resources

often include both a simple keyword search tool along with more advanced searching

features. There are general repositories and referitories (e.g., Wisconsin Online and

MERLOT) and discipline specific (e.g., ILumina). To meet with success faster, it is

important to determine which type of repository or referitory will most likely include the

desired learning object.

One of the oldest and best-known general referitories is MERLOT. MERLOT

describes itself as ba free and open resource designed primarily for faculty and students

of higher educationQ (MERLOT Website, 2003). MERLOT includes links to online

learning materials along with annotations, which include peer reviews and assignments.

Because MERLOT collects learning materials, not everything in MERLOT is a learning

object. Nevertheless, it does contain quite a few. MERLOT includes both a simple key

word search, as well as advanced searching tools. One can also browse the referitory

through MERLOT’s own subject indexing terms. There are several other well-known

referitories; refer to the table (see Fig. 3) for a more complete listing.

One of the newer and higher quality repositories is Wisconsin Online. The Wisconsin

Online Resource Center is a project of the Wisconsin Technical College System. This

repository allows faculty within this system to create and store their learning objects, but

anyone can view and make use of these learning objects. Because Wisconsin Online has

criteria which must be met in order for a learning object to be stored in its repository,

the quality of learning objects is fairly high. Like MERLOT, it includes both a simple

keyword search, as well as advanced searching tools. It is also possible to browse the

repository through its own subject indexing terms. See the table (Fig. 3) below for a

listing of other repositories.

Besides repositories and referitories there are several other locations to search on the

Internet to locate learning objects. One possibility is educational entertainment sites.

These sites include, but are not limited to, Public Broadcasting Services, The Learning

Channel, The History Channel, and National Geographic. These media broadcasters are in

the business of producing educational print and media resources. Recently, they have

begun creating interactive Web-based multimedia resources in concert with their

200

J.D. Shank / Research Strategies 19 (2003) 193–203

Fig. 3. A sample of learning object resources.

traditional media programs. Some of these multimedia resources qualify as learning

objects. Many of the learning objects that these sites create are geared for K-12, although

this does not preclude someone in higher education from using K-12 learning objects

when appropriate. Consequently, when searching for learning objects it is important to

attend to the intended audience as well as the content in making selections.

All of the aforementioned broadcasters have Web sites from which one can access the

learning objects they create. Most provide a key word search. Since most of these

broadcasters do not refer to the multimedia resources they create as learning objects, the term

should not be used in the key word search. There are two primary methods for searching for

learning objects on these sites. First, since these Web sites gear their resources for K-12

education, they usually have a section for teachers. When going to this section, it is often

possible to select teaching materials, supplements, or resources that will take one to various

learning objects based on the broadcaster’s programming. Alternatively, one can also search

by topic within current or archived programming. Once an appropriate program is found, one

will often be directed to additional resources or teaching materials, which in turn may point to

useful learning objects.

Other locations that can be searched to locate learning objects are government and

museum Web sites. Similar to the educational entertainment Web sites, these sites have

J.D. Shank / Research Strategies 19 (2003) 193–203

201

begun producing educational, interactive, Web-based, multimedia resources. NASA

produces numerous resources for K-12 teachers, and some of the materials they produce

meet the criteria for learning objects and would be appropriate for undergraduate

freshmen and sophomores learning about physics and astronomy. Likewise, the Museum

of Modern Art has created a number of resources to educate the public about art and art

history, and again, some of these resources would be considered quality learning objects

for those studying art. Like the aforementioned broadcaster sites, government and

museum sites can be searched in the same manner, both by using the basic and advanced

key word search tools and by going to the section for teachers, when it is an option. The

key here is to use subject-relevant government and museum sites.

Finally, Internet search engines can be used to locate learning objects. Internet search

engines should be viewed as the last option when searching for learning objects because they

offer the lowest ratio of reward to time invested. Search engines should not be ignored,

because it is possible to locate very useful and appropriate learning objects through a search

engine that would not have been found through any other means. However, be prepared to

spend more time and effort when using search engines.

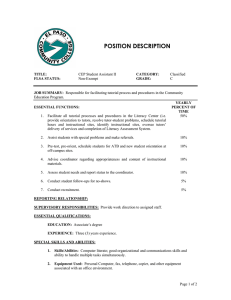

Today’s search engines (i.e., Google, AlltheWeb, Altavista, etc.) offer both simple and

complex keyword search tools. It is recommended to only use the advanced search tools

when attempting to locate learning objects. Search engines have various advanced search

tools and are different sizes. In general, it is most desirable to search the largest search

engines that offer the best advanced search tools in order to be able to locate learning objects

as quickly and efficiently as possible. Search engines like Google, AlltheWeb, and Altavista

are good starting places.

When using these search engines, apply the aforementioned identified keywords relating to

the subject or name of the learning object and also apply such words as tutorials, simulations,

learning modules, and presentations as these words often refer to types of learning objects. In

Fig. 4. Using search engines.

202

J.D. Shank / Research Strategies 19 (2003) 193–203

some search engines, such as Altavista and Alltheweb, it is possible to identify the format of

the learning object sought. This can be especially helpful in identifying the variety of

activities the learning object may contain. It is also important to identify the source of the

learning object, whether it comes from an institute of higher education, a professional

organization, a commercial site, or a government site. Finally, it may be desirable to search

for learning objects that have been developed within the last few months in order to locate the

most up-to-date content (see Fig. 4).

4. The future of learning objects

Learning objects offer numerous benefits and in future years, as they become more

mature, standardized, searchable, and commonplace, they will become even more

important. Reference and instruction librarians, as information gatherers and disseminators

and as educators, should play a vital role in utilizing learning objects to enhance their

library and information literacy instruction sessions, in addition to assisting instructors in

searching and locating useful existing learning objects.

The library field has seen tremendous change and librarians must not lose sight of

their primary roles, which have changed little over the centuries: to locate, collect,

organize, analyze, and distribute information. Learning objects present yet another

opportunity to assist both faculty and students in the teaching and learning process by

allowing librarians to be an intermediary and facilitator for locating, sharing, and using

these resources. In so doing, librarians can only strengthen the ties they have with faculty

and increase the profession’s visibility and relevance to the academic community.

References

Boskic, N. (2003, July). Learning objects design: What do educators think about the quality and reusability of

learning objects? Proceeding of the 3rd IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies.

Greece: Athens Available: http://csdl.computer.org/comp/proceedings/icalt/2003/1967/00/19670306.pdf.

Accessed December 14, 2003.

Friesen, N. (2003). Three objections to learning objects. Learning objects and metadata. London7 Kogan.

Available: http://phenom.educ.ualberta.ca/~nfriesen/. Accessed July 1, 2003.

L’Allier, James J. (1997, April). Frame of reference: NETg’s map to the products, their structure and core beliefs.

NetG. Available: http://www.netg.com/research/whitepapers/frameref.asp. Accessed July 9, 2003.

Learning Technology Standards Committee. (2001, April 18). Draft Standard for Learning Object

Metadata, Version 6.1. IEEE. Available: http://ltsc.ieee.org/doc/wg12/LOM_WD6-1_1.pdf. Accessed May

19, 2003.

OCLC E-Learning Task Force (2003, October). Libraries and the enhancement of e-learning. Online Computer

Library Center, Inc. Available: http://www.oclc.org/index/elearning/default.htm. Accessed December 19, 2003.

MERLOT. (2003). MERLOT: Multimedia educational resource for learning and online teaching. Available:

http://www.merlot.org/. Accessed July 8, 2003.

Merrill, D. (2002, April). Position statement and questions on learning objects research and practice. American

Educational Research Association (Annual Meeting) New Orleans, LO. Available: http://www.learndev.org/

LearningObjectsAERA2002.html. Accessed July 22, 2003.

J.D. Shank / Research Strategies 19 (2003) 193–203

203

Metros, S. E., & Bennett, K. (2002, October 1). Learning objects in higher education. Research Bulletin, 19.

ECAR. Available: http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ecar_so/login.asp?reason=denied_empty&script_

name=/ir/library/pdf/ecar_so/erb/ERB0219.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2002.

Morley, B., & Reifman, K. (2003). Interactive Boolean search tutorial. Bobst Library at NYU. Available: http://

www.nyu.edu/library/bobst/info/instruct/tutorials/boolean/boolean.html. Accessed May 18, 2003.

Polsani, P. R. (2003, February 19). Use and abuse of reusable learning objects. Journal of Digital Information,

3(4).

Rehak, D., & Mason, R. (2003). Keeping the learning in learning objects. In A. Littlejohn (Ed.), Reusing online

resources: A sustainable approach to eLearning. London7 Kogan.

Shepherd, C. (2000, December). Objects of interest. TACTIX. Available: http://www.fastrak-consulting.co.uk/

tactix/features/objects/objects.htm. Accessed July 9, 2003.

Weller, M. J., Pegler, C. A., & Mason, R. D. (2003, February). Putting the pieces together: What working with

learning objects means for the educator. Elearn International. Scotland: Edinburgh. Available: http://

iet.open.ac.uk/pp/m.j.weller/pub/. Accessed December 14, 2003.

Wiley, D. A. (2000). Connecting learning objects to instructional design theory: A definition, a metaphor, and a

taxonomy. The instructional use of learning objects: Online version. Available: http://reusability.org/read/

chapters/wiley.doc. Accessed May 18, 2003.

Wiley, D. A. (2002). Learning objects—A definition. In A. Kovalchick, & K. Dawson (Eds.), Educational

technology: An encyclopedia. Santa Barbara7 ABC-CLIO. Available: http://wiley.ed.usu.edu/docs/encyc.pdf.

Accessed May 18, 2003.