Stray Animal Control Practices (Europe)

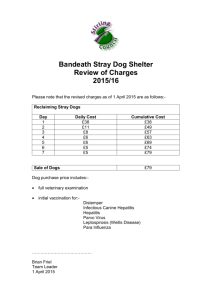

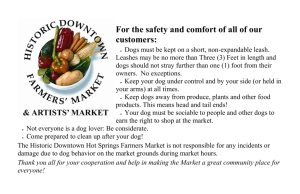

advertisement