Remembering Bob Hoffman

advertisement

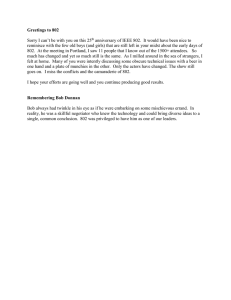

IRON GAME HISTORY V OLUME 3 NUMBER 1 Remembering Bob Hoffman Terry Todd, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin your ability in your chosen sport—including tennis—than to train with weights? Did you know that Harry Hopman has all his Davis Cup athletes on a heavy program of barbell and dumbell training? Sedgman, Hartwig, Hoad and Rosewall all use the weights religiously. I’ve been all over the world and it’s a wonderful thing to see so many young men everywhere using barbells, eating properly and following the Bob Hoffman rules of healthful living. I’ve dedicated my life to earning the title of World’s Healthiest Man so that I can use that title to build a stronger, a healthier and a better America.” He continued, awash in words, and as he continued, I looked at the big man in front of me, who was familiar to me before that day only through photos in his magazine. Full-chested, he stood at least as high my own 6’2” and his small blue eyes were set deep in a thinlipped face with skin pulled so tightly up and over his virtually hairless head that he reminded me vaguely with his rapid yet soft delivery of a hyperactive turtle. He went on, “I’m sorry you weren’t here a couple of days ago. Most of the men on the U.S. Olympic Lifting team were here—Berger, Vinci, Kono—everyone, and they had quite a session. World record after world record. I brought over a new stress-proof York Olympic Bar from the machine shop and they really gave it a workout. We make the finest bar on the market, and the finest weights and equipment for the money. But our men couldn’t handle the weights they do without regular use of Hoffman’s Hi-Proteen. It might surprise you to learn that at the last Olympic Games I had hundreds of pounds of Hoffman products flown to Australia so that I could distribute them to all our athletes—not just the lifters. Do you think Al Oerter would have done as well as he did, or Parry O’Brien, or Harold Connolly, or our whole team, without Hoffman’s Hi-Proteen? York Barbells and Hoffman’s Hi-Proteen. They’re hard to beat.” By that time in what, for want of a better word, I’ll call our conservation, I had forgotten all about the grime, the disarray and the generally beat-up nature of the gym. I was a twenty-year-old lifting fanatic, overwhelmed and amazed to find that Hoffman talked exactly as he wrote in his countless articles in Strength & Health, most of which I had read. He seemed somehow surreal as he leaned toward me, talking not so much with me as talking in my presence, sweeping me along with his rhetorical broom, ending at last with, “Well, I’d better be going now, I have to go home and get ready for a trip to Harrisburg tonight for a talk to a civic group there. I’ll break a few chains and do an abdominal vacuum. I’ll try my best to sell them all on the idea of following the Bob Hoffman Rules of Healthful Living. Nice talking with you, and remember what I said about weight training helping your tennis game. And don’t forget your HiProteen.” As he walked away—head up, chest out, striding straight I first met Bob Hoffman in the summer of 1958, a few days after I’d competed in the national intercollegiate tennis championships in Annapolis, Maryland. I was traveling home with a couple of my University of Texas teammates and, on our way to visit New York City, I talked them into a side trip to York, Pennsylvania, which I described as being the center of world weightlifting— a “Mecca for lifters everywhere” was how I put it, much to my later regret. What happened in York was that after driving a couple of times along the street on which the famous York Barbell Club gymnasium was supposedly located, I knew that something must be wrong. All the buildings in the area looked so woebegone and mangy, so unlike the way I absolutely knew the York gym would look Having read Bob Hoffman’s articles in his magazine, Strength & Health, for years, I had a clear image of a spacious, even majestic, building filled with purposeful, muscular young men either exercising with a variety of modern weight training equipment or packaging similar equipment for shipment to other purposeful, muscular young men throughout the world. Finally, unable to reconcile this image with any of the buildings on that section of Broad Street, I asked a passerby where I might find the York Barbell Company. “Hoffman’s place?” he said, “sure, that’s it over there,” and pointed to a building straight out of Upton Sinclair. My friends looked at me and smiled. But we were there, so we parked walked in, found a flight of dimly lit stairs and climbed to the second floor, which consisted of a large, unkempt room tilled with a seemingly haphazard clutter of barbells, dumbells and exercise equipment, most of which seemed in bad need of a major overhaul. A skinny boy in a dirty T-shirt was over in the comer doing a set of curls and flies buzzed in and out of the screenless windows. “Welcome to Mecca,” said one of my teammates. The other, laughing, finally managed to say, “Hey, let’s leave the old pilgrim to his prayers and see if we can find us a hamburger joint,” and down the stairs they went, still laughing. Feeling somewhat down in the mouth, I wandered over to a wall with photographs of old-time strongmen and tried to forget how long the drive back to Texas was going to be. After a few minutes, even the teenager left, and gradually I became lost in the wonderful old photos. Thus it was that I didn’t hear the man come up behind me until he tapped me on the shoulder and said, as I turned, “Hello, my name is Bob Hoffman. I’m the coach of the U.S. Olympic team, and I just might be the world’s healthiest man.” He shook my hand and asked, “Where are you from?”— then went on before I could answer. “I can tell from the way your right tennis shoe is wearing that you drag your foot when you serve. And by the way, did you know that no finer way exists to improve 18 IRON GAME HISTORY SEPTEMBER 1993 of the guardian of pure waters. “It’s about your washing proceon into the future—I wasn’t sure whether five minutes had passed or dure, Mr. Hoffman,” the little man began. “It just isn’t up to snuff. fifty, but I was sure of one thing—the “Mecca for lifters everywhere” Now I know you made some changes, but we still found a few soap might be a little on the grubby side, but the number one prophet was suds downstream and we have to put a stop to it. What’s more, we. alive and, well, unbelievable. I was still shaking my head a few moments later when my . .” At this point Bob stepped a little closer to the other man, accentuating the ten inches or so of height difference between them, and buddies came in smelling of meat grease, burnt cheese and onions— unlimbered his most awesome muscle—his tongue. “A fine thing it heads down, palms pressed to palms, chanting. But I had met Bob is when a man sacrifices tens Hoffman: they didn’t bother of thousands of dollars to me a bit. provide crystal clear Blue That was thirtyRock Mountain Springwafive years ago. Now I’m ter to the people of Pennalmost as old as Bob was sylvania and surrounding when I first met him. I’ve states, and then the governspent some of the intervenment threatens to throw the ing years humping iron, handcuffs on him. You may swilling such nostrums as not be aware of it, sir, but I Hi-Proteen and even workhave dedicated my life to ing, for a time, for the York building a stronger, a healthBarbell Company as an ediier, a better America, and tor of Strength & Health. that can’t be done without As for Bob, for more than good water. Do you know twenty more years he mainwhat’s actually in the city tained the position he had water where you live? Well held since the Thirties—as let me tell you, it would one of the main men of amaze, startle and frighten muscle in the Englishyou. So what if there is a speaking world. soapsud or two downstream Over the last from my plant? Tell me, twenty-five years of his life, what do you use when you I saw a good deal of Bob, clean your hands, your face, and I grew even more your body or your clothes? amazed by him as time Soap. You use soap. What, went by than I had been that I ask you, could be cleaner summer afternoon in York than soap? A man who has when he tapped me on the spent hundreds of thousands shoulder and made me feel of dollars to improve the as if I were already in the physical condition of the spacious, tidy gym, in the youth of America finds it spacious, tidy building his hard to believe that a reprepromotional ability later sentative of the government provided the funds to crewould try to drive him out ate. of business for putting a little I remember an afternoon almost thirty years ago This photo was taken in November 1978, several days before clean soap into a creek when a half when I rode with Bob over to the Bob Hoffman’s eightieth birthday. Bob, in his trademark be- mile downstream from where we’re Blue Rock Mountains in Pennsyl- medaled coat, stands with Terry Todd outside the offices of the standing right now a big herd of vania, where he had recently built a York Barbell Company. At their feet is the legendary dumb- Holstein cows are out in the middle of the same stream and unloadsmall plant to bottle water from a ell of Louis Cyr. PHOTO: TODD-MCLEAN C OLLECTION ing. And what they’re unloading is flowing spring. We were to meet several times worse than any soap, let me tell you. Go arrest those a man from the water quality control department and to see what cows and leave a man in peace whose only goal is to improve the needed to be done to comply with their standards. When we arrived, strength and health of our nation. Go and check the quality of the we could see the government man over by the main building, so Bob water in Philadelphia or Pittsburgh and quit badgering a man whose walked over and reached out his big hand to shake the smaller hand 19 IRON GAME HISTORY V OLUME 3 NUMBER 1 only aim is to convince the public of the need for pure water and then to supply it. If you took your job seriously, sir, you would spend what time you have left before retirement trying to alert people to the dangers of city water and spreading the good word about Bob Hoffman’s Blue Rock Mountain Springwater .” During the entire diatribe I noticed that the man from the government seemed to struggle to remain upright. He appeared to be physically buffeted, even though Bob never touched him It was as if the man stood in the teeth of a heavy gale. Finally, he shook his head, retreated several steps, held up his hands and said, “Okay, Mr. Hoffman, okay. We’ll get back to you.” He then got into his dark green Chevrolet sedan and drove slowly away. Chutzpah, apparently, can reach world class levels in rural Pennsylvania quite as well as in Manhattan. Attend for further evidence to the following story. Returning to York one evening after a trip out of town in 1965, Bob and I were talking about our various relationships with women, and I asked him if he had ever had any real problems with Alda, his common-law wife of quite a few years. “Alda’s a wonderful woman,” he began. “ In all our years together we’ve seldom had a cross word. The only thing she faults me for is what she calls being unfaithful. Unfaithful! Look at it this way.—I’ve been seeing the same four women—not counting Alda, of course-for over twenty-five years, at least once a week when I’m in town. At least once a week. The same four women! If that’s not being faithful, I don’t know what faithful means.” Knowing and being somewhat in awe of Alda myself, I could understand why he felt that she was a wonderful woman, and certainly why he tried to avoid cross words with her. Though possessed of a merry, expansive nature, she also had an explosive temper and, at around two hundred active pounds, the heft to back it up. During the time I lived in York she owned a big dancehall called the Thomasville Inn, where she did her own bouncing. On Saturday nights I usually went to the Inn to have a few beers and to watch Alda and Bob dance those spinning, heel-lifting polkas they loved and did so well. Bob was smitten by Alda some fifty-five years ago at a lovely spot called Brookside Park, about eight miles outside York in the small town of Dover. She was then only nineteen, about twenty years younger than Bob. He loved her from the start, showing his love as only he would. “She was a wonderful looking young woman,” he told me once, “so fresh and healthy. I used to do a lot of chainbreaking then, putting big chains around my chest and breaking them by expanding my ribcage, and when I first met Alda I wanted to show off a bit. I broke a bigger chain for her than I’d ever been able to break, and I was never able to break so large a one again.” As Bob was wont to do, he wove this episode into the warp and woof of his later life, citing it as the reason for the problems he had with his heart over the last years of his life, problems which began with a bit of arrhythmia, proceeded to auricular fibrillation, and culminated early in 1977 in heart bypass surgery. “Apparently,” Bob said, “I must have nicked an artery near my heart in some way when I broke that heavy chain for Alda. Even the heart of the world’s healthiest man isn’t immune to the powers of love.” The trauma of open heart surgery, and his ability to withstand it at the age of seventy-nine, were interpreted by Bob in a way quintessentially his own. “According to what my doctors said,” he explained, warming to the subject of his health, “I was almost fifteen years older than any other man on whom the same operation had been performed. They told me that my remarkable physical condition was what convinced them that I could come through the surgery. It seems to me that if any further proof was needed that I am truly the world’s healthiest man, my complete recovery from such a major operation at the age of seventy-nine would supply it. After all, not having had a cold or a headache, or missing a day of work due to illness since I was ten, are things of which I am justifiably proud. I’ve been able to live the physically, mentally, and sexually active life I’ve lived for the last forty years in spite of a nicked artery and then, in my eightieth year, I was able to withstand an operation that would have turned an ordinary older man into a vegetable. This is the best tribute I know to the Bob Hoffman Rules of Healthful Living.” As a matter of straight fact, leaving aside Bob’s tendency to raise mythomania to an art form, his health and vigor were remarkable, especially for a person who pushed himself as hard and traveled as much as he did through the years. Those who knew him best, however, suspect that his secret resided less in his rules for healthful living than in his almost supernatural will to be healthy, his will to keep going, to fight the good fight and even, if necessary, the bad. Clearly, he was this way from childhood. “At the age of four,” he liked to tell, “I ran one hundred times around a double tennis court and it felt so easy that I kept running for distance, finally progressing to the point where I won, at the age of ten, a ten mile race—a modified marathon—for boys sixteen and under.” Whether he actually did run one hundred times around those courts, or won a race of ten miles at the age of ten is hardly important all these years later. What is important, it seems to me, is that Bob said and wrote so often that he did do these things that they assumed for him the aspects of truth. They were part of his idea of himself, part of the self-making of a man, part of the ladder he built as he climbed it. The law of adverse possession in many states works much the same way; if you possess a thing–“squat” on a piece of land, for instance–openly, notoriously, and continuously for seven years under “color of title” or for twenty-one years without, it becomes yours in law as well as in fact. Bob literally possessed his many stories by asserting them so often for so long. Bob was born on 9 November 1898 in Tifton, Georgia, while his father was engineering the construction of a dam nearby, but Bob grew up in Pittsburgh. He lived near both sides of his family, and he always maintained that his athletic precocity was matched by his desire for self-improvement and financial success, which is saying a good deal. “Oh, I had lots of schemes to make money as a boy,“ he admitted, “from hauling water to washing windows to selling more peanuts at Forbes Field than any kid in the park. And I never neglected my mind. We lived fairly close to the Carnegie Library, and I remember reading sixty books one summer.” Off and running in more ways than one, Bob never stopped, and by the age of eighty, he headed an empire worth between twenty-five and thirty million dollars. He began to make his mark in the oil burner business, but in the Twenties he became deeply interested in the strength and fitness fields, and by the early Thirties he had gotten out of oil burners, founded the York Barbell Company and begun publication of Strength & Health magazine, the primary tract through 20 IRON GAME HISTORY SEPTEMBER 1993 activity? Think of that! Think how wonderful it would be if even a significant minority of those thirty seven million could be convinced that a little weight training would make them better players; that Hoffman’s Hi-Proteen and other food supplements would do more for their games than hot dogs, beer and cigarettes, and that following my rules for healthful living could make them not only better athletes but better husbands, better wives, better workers, better lovers. “As a nation, we’re in pitiful condition,” Bob added, really rolling by then. “We continue to fall further and further down the list of the healthiest countries in the world in terms of obesity, infant mortality, longevity, circulatory problems and in the physical fitness of our children, even though we’re the wealthiest country in the world. The situation is desperate. We eat too much of many things and too little of others; we smoke, we drink, we either take no exercise or insufficient exercise and we try to make up for it by taking more pills-more life-sapping drugs-than any nation on the face of the earth. I’ve been around a long time now and I’ve seen a lot—I’ve been to 108 foreign countries—and what I see disturbs me deeply. I fear for our nation, both physically and morally. I love the United States and I always have. I fought for this country in the First World War, and ever since then I’ve been working eighteen hours a day to do my part to build a stronger, a healthier, a better America. If I can influence even a few of the millions of softball players to live wiser, healthier lives, I’ll feel that whatever money I’ve put into the sport has been well invested.” Just how subject these thirty-seven million folks might have been to Bob’s influence was interesting to consider on the occasion of the only one of his several eightieth birthday parties actually to be held on his birthday. Almost a thousand people—ninety-five percent of whom were softballers—crowded into Wisehaven Hall in York to say thanks to Bob for all he’d done for them, which included paying for the roast beef and chicken dinner. He had also paid for the eight-page pamphlets which graced each placesetting. The pamphlets were filled with photos and information on the highlights of Bob’s life and, of course, they contained his rules for healthful living. As the softballers took their seats, loud chuckling could be heard as the guests began reading through the list of twelve rules. “Avoid alcoholic beverages,” a voice said. “If that means beer, forget it,” said another, to explosive laughter. “If old Bob drank a six pack every few days, I’ll bet he’d still have his hair.” More laughter. “Hey, look at rule number twelve—‘Avoid sexual indiscretions’— what in hell’s that supposed to mean?” someone questioned. “I think it means don’t get caught.” came the answer. “Old Bob write that? He must be slowing down some.” More laughter. And so on. Whatever eventual effect Bob’s one million plus may have had on the strength and health of either the softball players of America or the balance sheets of the York Barbell Company, it did add to his growing reputation in the York area as a doer of good, and costly deeds. Famous for years in his hometown only for his exploits in lifting and for his recurrent violations of his own rule number twelve, Bob gave freely in the last decades, and his gifts have been appreciated. Outside Carlisle, Pennsylvania, he purchased and developed an eleven hundred acre property as a YMCA campsite. Near which he spread his particular gospel of exercise and nutrition. He later diversified, and his business interests included not only the manufacture and sale of exercise equipment, health foods of all sorts, and the aforementioned springwater but also a precision equipment company, an automatic screw company, two foundries and a sizable chunk of York County real estate, both urban and rural. But the double core of it all was the making and selling of exercise equipment and health foods, which combined to bring in a gross annual income of around fifteen million dollars in 1977, according to the late John Terpak, the former general manager of the York Barbell company. Terpak was with the company from the middle 1930s until he died suddenly this past summer, as was Mike Dietz, who was the company’s treasurer until his death, and much speculation exists in the iron game about their often hostile relationship. There are some close students of Hoffman Behavior who say he fostered this animosity through the years in order to keep the two men from joining forces against him. According to this theory, Bob orchestrated the dissonance, refusing to make either of them the other’s boss, even— perhaps especially—in minor matters. Whatever the strength or weakness of that theory, the fact remains that Terpak and Dietz did have many differences of opinion regarding the business. Take the issue of softball, In the early Seventies, Bob’s lifelong interest in watching both baseball and softball began to shift toward an interest in sponsoring teams in softball, which he correctly perceived to be a growing, family-oriented recreational activity. Gradually, his sponsorship grew to the point at which, in 1977, he was outfitting and covering all the expenses of no fewer than fourteen full teams, all but one in the York area. So committed did he become, in fact, that he built a complex of five softball fields and paid two hundred thousand dollars for the complete renovation of a former minor league baseball stadium—the centerpiece of the Bob Hoffman Softball Complex. By conservative estimate, Bob’s investment in softball during the Seventies amounted to a million dollars, far more than he put during the same period into the national and international lifting teams which for decades had been the main recipients of his largesse. But even to a man with Hoffman’s cash flow, a million dollars was a great deal of money—far too much money, in the opinion of general manager Terpak, who felt that the million dollars had been more or less poured down a rathole. Treasurer Dietz, on the other hand, said, “It’s Bob’s money. Let him blow it any way he likes. Besides, he’s been right before when most of us were wrong, so maybe he’s right again.” As a philanthropy, of course, and not as an investment, the million can easily be seen to have been of great benefit to the sport and the community. The people at the American Amateur Softball Association, in fact, were so enamored of Bob that they installed him in their Hall of Honor. The question, though, is whether Bob cast this bread on the water with the hope of returns other than the predictable kudos from York township and softball officialdom. As is often the case with Bob, his motives were complex, if transparent. “I’ve always loved watching ball games,” he said in 1978, “and a few years ago I began to realize the enormous potential softball had to change people’s lives. Do you realize that as many as thirty-seven million people in the U.S. alone participate in this 21 IRON GAME HISTORY V OLUME 3 NUMBER 1 York, he donated several hundred prime acres for use as a public park. At York Hospital, he contributed one hundred thousand dollars toward the construction of a new physical therapy facility. In the city of York he bought a former bank building and had it restored and remodeled for the Y.M.C.A Through the foundation which bears his name, he sent many young people through college, as well as doing such small but thoughtful things as helping a local high school band make a long, expensive trip; sponsoring scholarships for excellence in journalism at York College; and donating a piece of land near his home in Dover for a regional police station and then outfitting the station with exercise equipment. Bob not only became a philanthropist in his later years, but a collector as well. For some time he and Alda, who were always fascinated by bears, filled every nook and cranny of their huge home with an amazing assortment of carved, molded, cast, blown, poured, and mounted bears of every shape, size and price range, from one dollar plastic figurines a few inches high to a full-sized adult polar bear, stuffed and lurking in their hallway. Surrounded by their bears, their other mementoes from Bob’s international trips, and their many farms, which were managed by Alda, they seemed to have a good life in their later years. Alda could set a four star Pennsylvania Dutch table with all the trimmings and she always saw that when Bob was home he had full access to his favorite foods, which included dandelion greens and ice cream mixed with what else but Hoffman’s Hi-Proteen. What he did not have full access to during some of those days, however, was his basement gym, which Alda padlocked following Bob’s open heart surgery. “That fool would’ve been down there the minute he got home,” Alda said, laughing, “I know him. He squeezed a pair of hand grip pers and kept tensing his muscles all the time he was in the hospital. I could’ve shot him.” “After my last examination,” Bob countered, “the doctors told me that I was free to lift whatever I wanted but all Alda has gotten for me out of my gym so far is a pair of five pound dumbells, a pair of ten pounders and a pair of twenties. I use them in my bedroom at least three times each week, between thirty and forty-five minutes each time, and I do between three and five miles of fast walking every day. Alda’s a wonderful woman but she’s a bit on the conservative side where exercise is concerned.” Being on the conservative side where exercise is concerned, however, was never to be a thing of which Bob himself could have been accused, even at the age of eighty. At that age, he not only still enjoyed and practiced regular exercise but he loved to watch sports— particularly, of course, weightlifting and powerlifting—and it would be safe to say that no man ever saw as much international competition in these two branches of heavy athletics as Bob Hoffman saw. His affair with weightlifting began seventy years ago and every Olympic Games since 1932 found him serving the US team in some capacity. He was the coach of the US team in every Games from 1948 to 1968, and his York Barbell Club lifters won the team trophy in the US Weightlifting Championships an incredible fortyeight times. In the younger but faster-growing sport of powerlifting, Bob had a hand on the helm at the beginning, sponsoring both the first nationwide championships (in 1964), the first official national championships (in 1965) and the first world championships (in 1971), as well as several subsequent national and world events. In November of 1978, in fact, he and Alda attended the world powerlifting championships in Turku, Finland. “I’ve always believed in the powerlifts and I’ve advocated them as a form of competition and as a way for athletes to train for improvement in their chosen sport,” Bob said at the national A.A.U. meet in San Antonio in 1978. “I supported them even when they were only done by men, but I’m doubly behind them now that the women are also deeply involved and I intend to stage and promote the World Championships for men in 1979 in such a way that it will be worth coming a long way to see. Not only will the audience get to see some of the strongest and best built men in the world they’ll also get to see some of the world’s strongest and most beautiful women. And while they’re here they can tour our world famous Weightlifting Hall of Fame at the downtown headquarters of the York Barbell Company, or go out to our main manufacturing plant and see how we make the finest barbells and health foods in the world. Hard to beat a package deal like that.” Those of us who were around Bob often forget through familiarity the effects of this sort of continuous self-promotion on the almost reverential way he was regarded in some parts of the world. At the World Championships in Finland, however, those of us so forgetful had a chance to see this reverence displayed. The most extreme example occurred one afternoon before the competition began. The team from India had just arrived and were checking in at the hotel desk when Bob came into the lobby wearing his coat-of-many-medals. As he walked toward them, one of the Indians looked up, saw Bob and began saying over and over again—chanting, really— “Bob Hoffman, Bob Hoffman, Bob Hoffman.” And as Bob walked up to them and extended his hand, half of the group actually knelt at his feet and—I may as well say it straight out-touched the hem of his garment as the mantra droned on, “Bob Hoffman, Bob Hoffman, Bob Hoffman.” Lest anyone imagine for a moment, however, that Bob was embarrassed by this display, or non-plused, nothing could be further from the easy, graceful way he accepted the veneration. The pope never drew breath who felt any more at home in the role of worshipee than Bob felt. He worked so hard and so long promoting himself, his business and his way of life that far him to hear his own words or sentiments on the tongues of others must surely have seemed part of the natural order of things. This limitless capacity to promote, though it was the sine qua non of his business success, often produced acute embarrassment among those around him. I, for one, will never forget a day in 1965 when I and several other lifters were at the airport with Bob, waiting to check our luggage for a cross country trip. The line was rather long and was moving slowly, so Bob commenced to enlighten everyone within earshot about who we were and where we were going. “You people were no doubt wondering,” he began, “just who this group of athletes was with their broad shoulders and thick chests. Well, they’re all national lifting champions of one sort or another, and we’re on our way to California to show them what the boys from the York Barbell Club can do when they try. This smaller fellow here (pointing to Bill March, then the national 198 pound champion) holds the world record. As for this bearded giant next to me (pointing, unfortunately, to me), this man mountain, this one man 22 IRON GAME HISTORY SEPTEMBER 1993 ments. I travel so often and have so much to do that with this untrustworthy memory I occasionally wake up wondering where I am and what I’m supposed to do that day. No doubt during my operation the arterial flow to my brain was temporarily cut off, resulting in this loss. A normal man, of course, would have been turned into an artichoke.” The bottom line on Bob may indeed be this ability to turn things to his own advantage, to see a horse when others see only horse-apples. And this ability, unlike his memory or his physical strength, seemed undiminished as he aged. For instance, a couple of days after Bob’s eightieth birthday, a softball church league in York held its annual dinner and Bob was are of the invited dignitaries, with me tagging along as his guest. What neither Bob nor I realized about the dinner was that although he was indeed a head table guest, he was not the main attraction, this honor belonging to Greg Luzinski of the Philadelphia Phillies. As custom dictates, the head table was served first, and as we were finishing our meal, one of the boys in the audience finally gathered his courage and walked up to ask Luzinski for an autograph, at which point scores of other kids began knocking chairs over in an effort to be the next one up there. The crush at the head table became so bad, in fact, that the master of ceremonies had to ask the boys and girls to form a line extending off to Luzinski’s left along the front of the table. And, after a lot of ‘me first’ jockeying, this was done. I was on Bob’s left while Luzinski was on his right, an arrangement which meant that the kids began to fidget past the two of us on the way toward Luzinski’s coveted signature. Bob sat still for a while, watching them pass, but finally he could stand the neglect no longer. “Hey, there,” he said to the ten year old directly in front of him, “do you know who this big guy is sitting here next to me (pointing, I realized with a flagging heart, to me)? Have you seen him on TV? Well, he’s the strongest man in the world, that’s who he is.” (Oh, no, I thought, not again, especially since I’d been retired by then for more than a decade. ) “Feel his muscle.” (The kid reaches over, tries to encircle my arm with his small hands, and goes, “Wow, Mike, take a look at this arm.“) This new buzz attracts attention and as kids crowd toward us to feel my “muscle,” the focus of attention begins to shift ever so slightly. Bob presses on, smelling blood, speaking now to each child as he or she passes in front, asking each one, “How big is that Luzinski, anyway? About 220, I’d say. Well, this guy here with me weighs well over 300 (about 270, actually). He makes old Greg look kind of puny now, doesn’t he? Feel that arm. He’s bigger than the Incredible Hulk I’m his coach, you know. He eats lots and lots of Hoffman’s Hi-Proteen. That’s why he made all those lifting records, and that’s why he was an All American football player at the University of Texas.” (Have mercy, I thought, never having played a single down of organized football anywhere.) As the kids clustered around us I was shaking my head and wishing for some hip boots, yet I had to laugh in spite of my embarrassment as kid after wide-eyed kid reached over to touch my arm and to ask for my autograph. And to ask of course, for Bob’s. crowd, well, he’s the strongest man in the whole wide world. (My God, I thought, I hope Paul Anderson doesn’t hear about this.) Hips like a quarter horse, shoulders like a bull, and a grip like a gorilla. Why he can crumple up a beer can—not that he’d ever drink a beer, mind you—like an ordinary man would wad up a Dixie cup.” And so on and on. By this time my turn had come and the ticket agent, who’d been unable to avoid hearing Bob hold forth about me and my “gorilla grip,” was eyeing me suspiciously. He bent to look at my suitcase, which, because of some sort of malf unctioning of the catch, I’d been unable to completely shut when I left home. He looked up and said sharply, “You failed to snap your bag.” At that point Bob stepped up, and said with a laugh, ‘Well, young man, if you can shut it I guess we’ll leave the big fellow here and take you to California.” And then, with Bob, my teammates and what seemed (still seems!) to be half the people in the terminal looking on, the agent—an average guy—bent down, placed both his thumbs on the catch and, snap!, shut the thing like a lunch pail. But, praise be, I have other memories, such as the time back in the mid-Sixties when Bob was confronted in my presence by Dr. Craig Whitehead, a young physician who questioned the medical and even the ethical underpinning of a recent Strength & Health article in which senior citizens everywhere were urged by Bob to consume lots of Hoffman’s Hi-Proteen as a hedge against the aging process. “What bothers me, Bob,” Whitehead said, “is that here I am, a healthy young man, in top lifting shape, and yet even I get gaseous when I eat much of that Hi-Proteen. Do you think that people in their sixties and seventies can metabolize all that soy flour?” “Well, after all,” Bob countered, without even a smidgen of hesitation, “what’s wrong with a little gas? Most of the men on the York team have always had a little gas. Grimek’s always had gas. And Stanko? Well! I’ll never forget one night back in the late thirties coming home from a contest in New York with a carload of our men. We’d stopped to eat at a beanery as we left the city. . .What a trip. Thank God it was a warm spring night and we could roll the windows down.” Besides this Jovean ability to rationalize, Bob also had a great gift for hortatory language—whether spoken or written down. A politic writer and speaker, he encouraged people through books, articles, pamphlets, speeches and courses to become stronger, healthier and better for almost sixty years, publishing during that time an astonishing amount of material. In all, though only God or a Univac could know for sure, Bob quite likely put into print somewhere around ten million words, all of them typed by his own hands, in that rambling, personal style. The reason he was able to crank it out so fast, other than his Brobdignagian capacity for work, was that until his last years he always had such a flypaper memory. Often, writing about lifting competitions he had attended, he would use no notes at all but could recall with precise detail every lift made or missed by every man in the meet, even if this meant remembering five hundred separate lifts. But age has a way of blunting even the sharpest of mnemonic tools, and Bob was honest about his loss, although he managed to give it his own characteristic spin. “I have to admit that my failing memory is a bother to me,” he said. “I have to constantly recheck my facts when I’m writing and I sometimes forget whether or not I have certain appoint- [The majority of the interviews in this article were done in the days just before and after Bob Hoffman’s eightieth birthday in York, Pennsylvania, in November of 1978.] 23