Managing Building Compliance Obligations (Existing

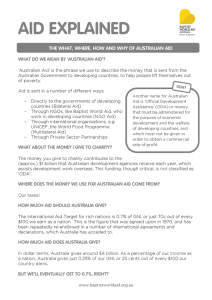

advertisement