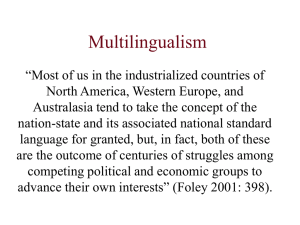

The Constellation of Languages in Europe

advertisement