2016 Emerging Technology Domains Risk Survey

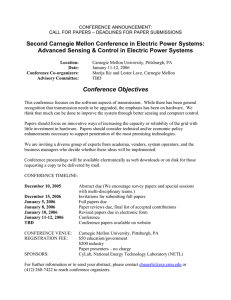

advertisement