On Track for Success - Everyone Graduates Center

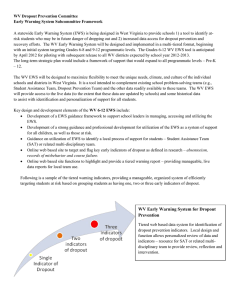

advertisement