Ise-Shima Progress Report

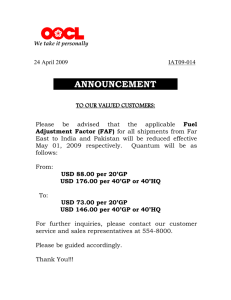

advertisement