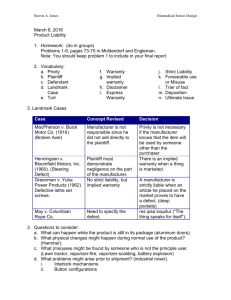

Manufacturing Defects - Scholar Commons

advertisement