Understanding Children`s Development (Pearson)

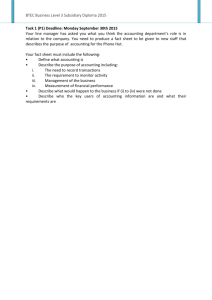

advertisement