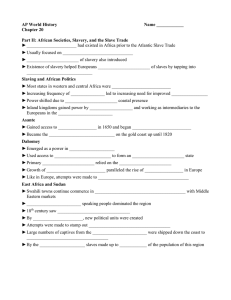

Slavery and Justice

advertisement