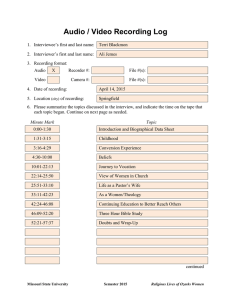

an exploration of rights management technologies used in the music

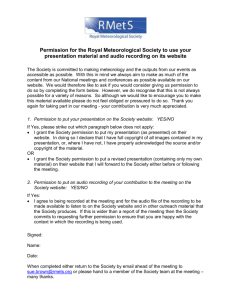

advertisement