A guide to MS - Pennine GP Training

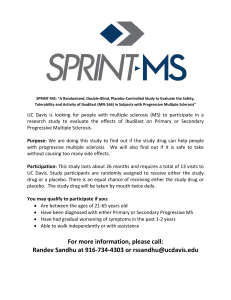

advertisement